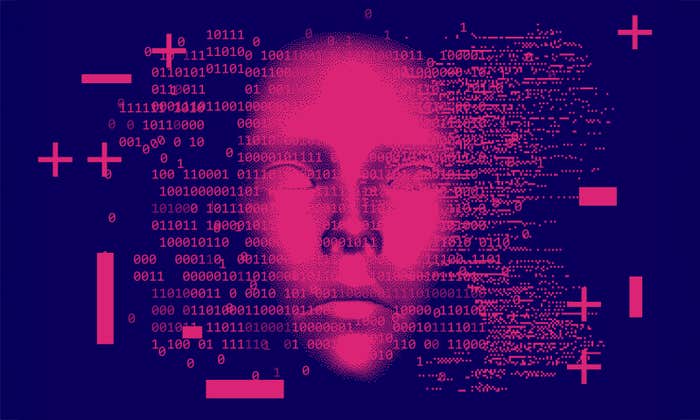

Over the span of 20 days early this year, artificial intelligence encountered a major test of how well it can tackle problems in the real world. A program called Libratus took on four of the best poker players in the country, at a tournament at the Rivers Casino in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. They were playing a form of poker called heads-up no-limit Texas hold ‘em, where two players face off, often online, in a long series of hands, testing each other’s strategies, refining their own, and bluffing like mad. After 120,000 hands, Libratus emerged with an overwhelming victory over all four opponents, winning $1,776,250 of simulated money and, more importantly, bragging rights as arguably the best poker player on the planet. Just halfway through the competition, Dong Kim, the human player who fared best against the machine, all but admitted defeat. “I didn’t realize how good it was until today. I felt like I was playing against someone who was cheating, like it could see my cards,” he told Wired. “I’m not accusing it of cheating. It was just that good.”

Libratus’s success is yet another triumph for artificial intelligence over the species that created it. When computers mastered the relatively trivial games of tic-tac-toe and checkers, nobody beyond computer scientists paid much attention. But in 1997, when I.B.M.’s Deep Blue beat chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov in chess, a game that geniuses have dedicated their lives to, there rose a wave of interest and concern about how smart computers would become. Recently the improvements in A.I. have come faster: In 2011, I.B.M.’s Watson topped the greatest (human) Jeopardy! champion of all time, and just last year, a program called AlphaGo beat Lee Sedol, one of the world’s best Go players—10 years before many researchers expected Homo sapiens to lose our stranglehold on that notoriously complicated game.

Libratus gives us tantalizing thoughts of computers handling complicated and important questions better than we ever could.

Poker may seem like just another step in A.I.’s march forward (toward dystopic global dominance, if you believe science fiction), but it may turn out to be one of the most significant. Unlike the other games, poker is an imperfect-information game. In chess and Go, you know where your pieces and your opponent’s are, and you project forward from that well-defined position; in poker, you don’t know what cards your opponent is holding face-down, and you must make decisions in the swirl of this uncertainty. Researchers say this is more difficult and, arguably, more important, since so many important decisions are based on incomplete information. Doctors look at patients, gather what evidence they can, and make life-or-death decisions, often without knowing what’s really happening within the body. Diplomats, business negotiators, and military strategists don’t know the true positions or intentions of their counterparts, and must formulate strategy based on complicated webs of possible actions and outcomes.

To A.I. researchers, poker programs aren’t just better ways to win a card game: They’re experiments to see how well computers can make decisions with imperfect information. For decades, they’ve been improving their programs in a race to try to match the current benchmark: us. Tuomas Sandholm, the creator of Libratus and a computer scientist at Carnegie Mellon University, has been wrestling with poker for 12 years. His previous creation, Claudico, lost to four poker pros in a similar tournament in 2015. A team at the University of Alberta recently announced that their program, called DeepStack, was the first to beat professional players in heads-up, no-limit Texas hold ‘em, though the participants in the casino tournament say the competition wasn’t as fierce. Now that computers have shown they can play poker better than people, they may be ready to use that skill to make better real-world decisions than us.

Creating a program clever enough to win required a clever approach; Sandholm relied on a technique called reinforcement learning. He and his students taught Libratus the rules of the game and gave it the simple goal of winning money, then let it play trillions of hands against itself, trying whatever moves it stumbled on. The program watched what worked and which didn’t, and used those observations to create its strategies. One apparent advantage of this is that Libratus was not limited to strategies developed by other poker players, and it sometimes came up with its own, counterintuitive moves. For instance, when Libratus is holding weak cards and its opponent raises the bet, the program sometimes raises right back. This may seem foolhardy, since it’s increasing the chances that its weak hand will lose big to an opponent who raised because they have a strong hand. “If my 10-year-old daughter made that move, I would teach her not to,” Sandholm told the Washington Post. “But it turns out that this is actually a good move. It helps to catch bluffs.” That is, if the opponent who raised the bet was bluffing, they might be alarmed by Libratus’s counter-raise, thinking the program had a strong hand, and would then fold. Libratus figured out it could outdo a bluff with a bigger bluff.

Many of the well-known recent advances in A.I.—like self-driving cars, facial recognition, and natural-language processing—depend on a different approach called machine learning, where computers pore over enormous data sets and draw conclusions from the patterns they see. Reinforcement learning, in contrast, may be better at getting computers to generate their own creative strategies. If that’s true, it would be no coincidence that both Libratus and AlphaGo used reinforcement learning to develop their human-surpassing skills.

Libratus gives us tantalizing thoughts of computers handling complicated and important questions better than we ever could, but the technology has advanced so quickly that it’s not yet clear when, how, or whether it will be successfully applied. In the near term, the program itself is not even much of a threat to its natural habitat. Libratus dominates poker played against only one opponent at a time; move to a table full of players and the calculations are more complicated, and Libratus would be out of its depth. Even in a one-on-one online game, Libratus is so computationally demanding (it ran on a supercomputer and used over 7,000 times the processing power and 17,000 times the RAM of a high-end laptop) that it’s impractial to use it beyond research. For now, the program is changing the world of poker in a different way—by schooling the human players. “We are definitely learning from how this computer thinks,” said Jason Les, one of the players vanquished by the machine. “I think I will come out of this a better poker player.”

Amos Zeeberg is a freelance science and technology journalist based in Tokyo.

WATCH: Ken Goldberg, a roboticist at the Automation Sciences Lab at U.C. Berkeley, on the most creative thing a robot has ever done.