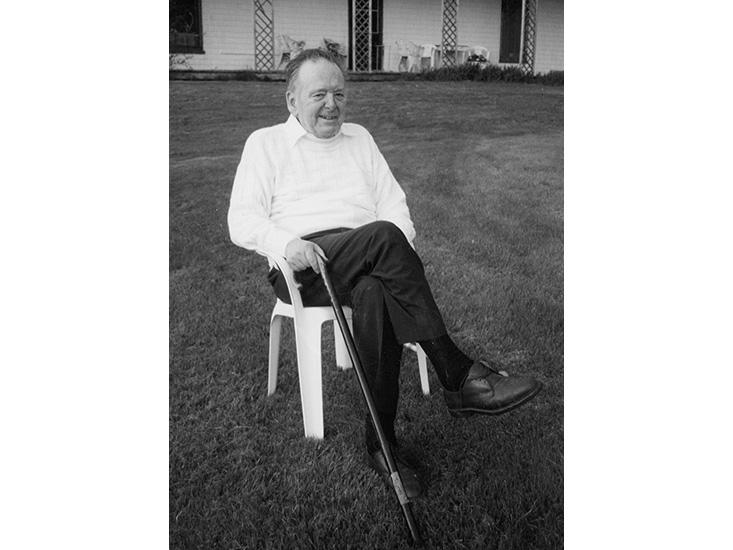

Julian Jaynes was living out of a couple of suitcases in a Princeton dorm in the early 1970s. He must have been an odd sight there among the undergraduates, some of whom knew him as a lecturer who taught psychology, holding forth in a deep baritone voice. He was in his early 50s, a fairly heavy drinker, untenured, and apparently uninterested in tenure. His position was marginal. “I don’t think the university was paying him on a regular basis,” recalls Roy Baumeister, then a student at Princeton and today a professor of psychology at Florida State University. But among the youthful inhabitants of the dorm, Jaynes was working on his masterpiece, and had been for years.

From the age of 6, Jaynes had been transfixed by the singularity of conscious experience. Gazing at a yellow forsythia flower, he’d wondered how he could be sure that others saw the same yellow as he did. As a young man, serving three years in a Pennsylvania prison for declining to support the war effort, he watched a worm in the grass of the prison yard one spring, wondering what separated the unthinking earth from the worm and the worm from himself. It was the kind of question that dogged him for the rest of his life, and the book he was working on would grip a generation beginning to ask themselves similar questions.

The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, when it finally came out in 1976, did not look like a best-seller. But sell it did. It was reviewed in science magazines and psychology journals, Time, The New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times. It was nominated for a National Book Award in 1978. New editions continued to come out, as Jaynes went on the lecture circuit. Jaynes died of a stroke in 1997; his book lived on. In 2000, another new edition hit the shelves. It continues to sell today.

Jaynes was sent to prison, where he had plenty of time to reflect on the problem of consciousness.

In the beginning of the book, Jaynes asks, “This consciousness that is myself of selves, that is everything, and yet nothing at all—what is it? And where did it come from? And why?” Jaynes answers by unfurling a version of history in which humans were not fully conscious until about 3,000 years ago, instead relying on a two-part, or bicameral, mind, with one half speaking to the other in the voice of the gods with guidance whenever a difficult situation presented itself. The bicameral mind eventually collapsed as human societies became more complex, and our forebears awoke with modern self-awareness, complete with an internal narrative, which Jaynes believes has its roots in language.

It’s a remarkable thesis that doesn’t fit well with contemporary thought about how consciousness works. The idea that the ancient Greeks were not self-aware raises quite a few eyebrows. By giving consciousness a cultural origin, says Christof Koch, chief scientific officer at the Allen Institute for Brain Science, “Jaynes disavows consciousness as a biological phenomenon.”

But Koch and other neuroscientists and philosophers admit Jaynes’ wild book has a power all its own. “He was an old-fashioned amateur scholar of considerable depth and tremendous ambition, who followed where his curiosity led him,” says philosopher Daniel Dennett. The kind of search that Jaynes was on—a quest to describe and account for an inner voice, an inner world we seem to inhabit—continues to resonate. The study of consciousness is on the rise in neuroscience labs around the world, but the science isn’t yet close to capturing subjective experience. That’s something Jaynes did beautifully, opening a door on what it feels like to be alive, and be aware of it.

Jaynes was the son of a Unitarian minister in West Newton, Massachusetts. Though his father died when Jaynes was 2 years old, his voice lived on in 48 volumes of his sermons, which Jaynes seems to have spent a great deal of time with as he grew up. In college, he experimented with philosophy and literature but decided that psychology, with its pursuit of real data about the physical world, was where he should seek answers to his questions. He headed to graduate school in 1941, but shortly thereafter, the United States joined World War II. Jaynes, a conscientious objector, was assigned to a civilian war effort camp. He soon wrote a letter to the U.S. Attorney General announcing that he was leaving, finding the camp’s goal incompatible with his principles: “Can we work within the logic of an evil system for its destruction? Jesus did not think so … Nor do I.” He was sent to prison, where he had plenty of time to reflect on the problem of consciousness. “Jaynes was a man of principle, some might say impulsively or recklessly so,” a former student and a neighbor recalled. “He seemed to draw energy from jousting windmills.”

Jaynes emerged after three years, convinced that animal experiments could help him understand how consciousness first evolved, and spent the next three years in graduate school at Yale University. For a while, he believed that if a creature could learn from experience, it was having an experience, implying consciousness. He herded single paramecia through a maze carved in wax on Bakelite, shocking them if they turned the wrong way. “I moved on to species with synaptic nervous systems, flatworms, earthworms, fish, and reptiles, which could indeed learn, all on the naive assumption that I was chronicling the grand evolution of consciousness,” he recounts in his book. “Ridiculous! It was, I fear, several years before I realized that this assumption makes no sense at all.” Many creatures could be trained, but what they did was not introspection. And that was what tormented Jaynes.

A psychology based on rats in mazes rather than the human mind, Jaynes wrote, was “bad poetry disguised as science.”

Meanwhile, he performed more traditional research on the maternal behavior of animals under his advisor, Frank Beach. It was a difficult time to be interested in consciousness. One of the dominant psychological theories was behaviorism, which explored the external responses of humans and animals to stimuli. Conditioning with electric shocks was in, pondering the intangible world of thoughts was out, and for understandable reasons—behaviorism was a reaction to earlier, less rigorous trends in psychology. But for much of Jaynes’ career, inner experience was beyond the pale. In some parts of this community to say you studied consciousness was to confess an interest in the occult.

In 1949, Jaynes left without receiving his Ph.D., apparently having refused to submit his dissertation. It’s not clear exactly why—some suggest his committee wanted revisions he would not make, some that he was irked by the hierarchical structure of academia, some that he simply was fed up enough to walk. One story he told was that he didn’t want to pay the $25 submission fee. (In 1977, as his book was selling, Jaynes completed his Ph.D. at Yale.) But it does seem clear that he was frustrated by his lack of progress. He later wrote that a psychology based on rats in mazes rather than the human mind was “bad poetry disguised as science.”

It was the beginning of an odd peregrination. In the fall of 1949, he moved to England and became a playwright and actor, and for the next 15 years, he ricocheted back and forth across the ocean, alternating between plays and adjunct teaching, eventually landing at Princeton University in 1964. All the while, he had been reading widely and pondering the question of what consciousness was and how it could have arisen. By 1969, he was thinking about a work that would describe the origin of consciousness as a fundamentally cultural change, rather than the evolved one he had searched for. It was to be a grand synthesis of science, archaeology, anthropology, and literature, drawing on material gathered during the past couple decades of his life. He believed he’d finally heard something snap into place.

The book sets its sights high from the very first words. “O, what a world of unseen visions and heard silences, this insubstantial country of the mind!” Jaynes begins. “A secret theater of speechless monologue and prevenient counsel, an invisible mansion of all moods, musings, and mysteries, an infinite resort of disappointments and discoveries.”

To explore the origins of this inner country, Jaynes first presents a masterful precis of what consciousness is not. It is not an innate property of matter. It is not merely the process of learning. It is not, strangely enough, required for a number of rather complex processes. Conscious focus is required to learn to put together puzzles or execute a tennis serve or even play the piano. But after a skill is mastered, it recedes below the horizon into the fuzzy world of the unconscious. Thinking about it makes it harder to do. As Jaynes saw it, a great deal of what is happening to you right now does not seem to be part of your consciousness until your attention is drawn to it. Could you feel the chair pressing against your back a moment ago? Or do you only feel it now, now that you have asked yourself that question?

Consciousness, Jaynes tells readers, in a passage that can be seen as a challenge to future students of philosophy and cognitive science, “is a much smaller part of our mental life than we are conscious of, because we cannot be conscious of what we are not conscious of.” His illustration of his point is quite wonderful. “It is like asking a flashlight in a dark room to search around for something that does not have any light shining upon it. The flashlight, since there is light in whatever direction it turns, would have to conclude that there is light everywhere. And so consciousness can seem to pervade all mentality when actually it does not.”

Perhaps most striking to Jaynes, though, is that knowledge and even creative epiphanies appear to us without our control. You can tell which water glass is the heavier of a pair without any conscious thought—you just know, once you pick them up. And in the case of problem-solving, creative or otherwise, we give our minds the information we need to work through, but we are helpless to force an answer. Instead it comes to us later, in the shower or on a walk. Jaynes told a neighbor that his theory finally gelled while he was watching ice moving on the St. John River. Something that we are not aware of does the work.

The picture Jaynes paints is that consciousness is only a very thin rime of ice atop a sea of habit, instinct, or some other process that is capable of taking care of much more than we tend to give it credit for. “If our reasonings have been correct,” he writes, “it is perfectly possible that there could have existed a race of men who spoke, judged, reasoned, solved problems, indeed did most of the things that we do, but were not conscious at all.”

Jaynes believes that language needed to exist before what he has defined as consciousness was possible. So he decides to read early texts, including The Iliad and The Odyssey, to look for signs of people who aren’t capable of introspection—people who are all sea, no rime. And he believes he sees that in The Iliad. He writes that the characters in The Iliad do not look inward, and they take no independent initiative. They only do what is suggested by the gods. When something needs to happen, a god appears and speaks. Without these voices, the heroes would stand frozen on the beaches of Troy, like puppets.

Speech was already known to be localized in the left hemisphere, instead of spread out over both hemispheres. Jaynes suggests that the right hemisphere’s lack of language capacity is because it used to be used for something else—specifically, it was the source of admonitory messages funneled to the speech centers on the left side of the brain. These manifested themselves as hallucinations that helped guide humans through situations that required complex responses—decisions of statecraft, for instance, or whether to go on a risky journey.

The combination of instinct and voices—that is, the bicameral mind—would have allowed humans to manage for quite some time, as long as their societies were rigidly hierarchical, Jaynes writes. But about 3,000 years ago, stress from overpopulation, natural disasters, and wars overwhelmed the voices’ rather limited capabilities. At that point, in the breakdown of the bicameral mind, bits and pieces of the conscious mind would have come to awareness, as the voices mostly died away. That led to a more flexible, though more existentially daunting, way of coping with the decisions of everyday life—one better suited to the chaos that ensued when the gods went silent. By The Odyssey, the characters are capable of something like interior thought, he says. The modern mind, with its internal narrative and longing for direction from a higher power, appear.

Daniel Dennett likes to give Jaynes the benefit of the doubt: “There were a lot of really good ideas lurking among the completely wild junk.”

The rest of the book—400 pages—provides what Jaynes sees as evidence of this bicamerality and its breakdown around the world, in the Old Testament, Maya stone carvings, Sumerian writings. He cites a carving of an Assyrian king kneeling before a god’s empty throne, circa 1230 B.C. Frequent, successive migrations around the same time in what is now Greece, he takes to be a tumult caused by the breakdown. And Jaynes reflects on how this transition might be reverberating today. “We, at the end of the second millennium A.D., are still in a sense deep in this transition to a new mentality. And all about us lie the remnants of our recent bicameral past,” he writes, in awe of the reach of this idea, and seized with the pathos of the situation. “Our kings, presidents, judges, and officers begin their tenures with oaths to the now-silent deities, taken upon the writings of those who have last heard them.”

It’s a sweeping and profoundly odd book. But The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind was enormously appealing. Part of it might have been that many readers had never thought about just what consciousness was before. Perhaps this was the first time many people reached out, touched their certainty of self, and found it was not what they expected. Jaynes’ book did strike in a particular era when such jolts were perhaps uniquely potent. In the 1970s, many people were growing interested in questions of consciousness. Baumeister, who admires Jaynes, and read the book in galley form before it was published, says Jaynes tapped into the “spiritual stage” of the ascendant New Age movement.

And the language—what language! It has a Nabokovian richness. There is an elegance, power, and believability to his prose. It sounds prophetic. It feels true. And that has incredible weight. Truth and beauty intertwine in ways humans have trouble picking apart. Physicist Ben Lillie, who runs the Storycollider storytelling series, remembers when he discovered Jaynes’ book. “I was part of this group that hung out in the newspaper and yearbook offices and talked about intellectual stuff and wore a lot of black,” Lillie says. “Somebody read it. I don’t remember who was first, it wasn’t me. All of a sudden we thought, that sounds great, and we were all reading it. You got to feel like a rebel because it was going against common wisdom.”

It’s easy to find cracks in the logic: Just for starters, there are moments in The Iliad when the characters introspect, though Jaynes decides they are later additions or mistranslations. But those cracks don’t necessarily diminish the book’s power. To readers like Paul Hains, the co-founder of Aeon, an online science and philosophy magazine, Jaynes’ central thesis is of secondary importance to the book’s appeal. “What captured me was his approach and style and the inspired and nostalgic mood of the text; not so much the specifics of his argument, intriguing though they were,” Hains writes. “Jaynes was prepared to explore the frontier of consciousness on its own terms, without explaining away its mysterious qualities.”

Meanwhile, over the last four decades, the winds have shifted, as often happens in science as researchers pursue the best questions to ask. Enormous projects, like those of the Allen Institute for Brain Science and the Brain-Mind Institute of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, seek to understand the structure and function of the brain in order to answer many questions, including what consciousness is in the brain and how it is generated, right down to the neurons. A whole field, behavioral economics, has sprung up to describe and use the ways in which we are unconscious of what we do—a major theme in Jaynes’ writing—and the insights netted its founders, Daniel Kahneman and Vernon L. Smith, the Nobel Prize.

Eric Schwitzgebel, a professor of philosophy at University of California, Riverside, has conducted experiments to investigate how aware we are of things we are not focused on, which echo Jaynes’ view that consciousness is essentially awareness. “It’s not unreasonable to have a view that the only things you’re conscious of are things you are attending to right now,” Schwitzgebel says. “But it’s also reasonable to say that there’s a lot going on in the background and periphery. Behind the focus, you’re having all this experience.” Schwitzgebel says the questions that drove Jaynes are indeed hot topics in psychology and neuroscience. But at the same time, Jaynes’ book remains on the scientific fringe. “It would still be pretty far outside of the mainstream to say that ancient Greeks didn’t have consciousness,” he says.

Dennett, who has called The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind a “marvelous, wacky book,” likes to give Jaynes the benefit of the doubt. “There were a lot of really good ideas lurking among the completely wild junk,” he says. Particularly, he thinks Jaynes’ insistence on a difference between what goes on in the minds of animals and the minds of humans, and the idea that the difference has its origins in language, is deeply compelling.

“[This] is a view I was on the edge of myself, and Julian kind of pushed me over the top,” Dennett says. “There is such a difference between the consciousness of a chimpanzee and human consciousness that it requires a special explanation, an explanation that heavily invokes the human distinction of natural language,” though that’s far from all of it, he notes. “It’s an eccentric position,” he admits wryly. “I have not managed to sway the mainstream over to this.”

The broader questions that Jaynes’ book raised are the same ones that continue to vex neuroscientists and lay people.

It’s a credit to Jaynes’ wild ideas that, every now and then, they are mentioned by neuroscientists who study consciousness. In his 2010 book, Self Comes to Mind, Antonio Damasio, a professor of neuroscience, and the director of the Brain and Creativity Institute at the University of Southern California, sympathizes with Jaynes’ idea that something happened in the human mind in the relatively recent past. “As knowledge accumulated about humans and about the universe, continued reflection could well have altered the structure of the autobiographical self and led to a closer stitching together of relatively disparate aspects of mind processing; coordination of brain activity, driven first by value and then by reason, was working to our advantage,” he writes. But that’s a relatively rare endorsement. A more common response is the one given by neurophilosopher Patricia S. Churchland, an emerita professor at the University of California, San Diego. “It is fanciful,” she says of Jaynes’ book. “I don’t think that it added anything of substance to our understanding of the nature of consciousness and how consciousness emerges from brain activity.”

Jaynes himself saw his theory as a scientific contribution, and was disappointed with the research community’s response. Although he enjoyed the public’s interest in his work, tilting at these particular windmills was frustrating even for an inveterate contrarian. Jaynes’ drinking grew heavier. A second book, which was to have taken the ideas further, was never completed.

And so, his legacy, odd as it is, lives on. Over the years, Dennett has sometimes mentioned in his talks that he thought Jaynes was on to something. Afterward—after the crowd had cleared out, after the public discussion was over—almost every time there would be someone hanging back. “I can come out of the closet now,” he or she would say. “I think Jaynes is wonderful too.”

Marcel Kuijsten is an IT professional who runs a group called the Julian Jaynes Society whose membership he estimates at about 500 or 600 enthusiasts from around the world. The group has an online members’ forum where they discuss Jaynes’ theory, and in 2013 for the first time they hosted a conference, meeting in West Virginia for two days of talks. “It was an incredible experience,” he says.

Kuijsten feels that many people who come down on Jaynes haven’t gone to the trouble to understand the argument, which he admits is hard to get one’s mind around. “They come into it with a really ingrained, pre-conceived notion of what consciousness means to them,” he says, “And maybe they just read the back of the book.” But he’s playing the long game. “I’m not here to change anybody’s mind. It’s a total waste of time. I want to provide the best quality information, and provide good resources for people who’ve read the book and want to have a discussion.”

To that end, Kuijsten and the Society have released books of Jaynes’ writings and of new essays about him and his work. Whenever discoveries that relate to the issues Jaynes raised are published, Kuijsten notes them on the site. In 2009 he highlighted brain-imaging studies suggesting that auditory hallucinations begin with activity in the right side of the brain, followed by activation on the left, which sounds similar to Jaynes’ mechanism for the bicameral mind. He hopes that as time goes on, people will revisit some of Jaynes’ ideas in light of new science.

Ultimately, the broader questions that Jaynes’ book raised are the same ones that continue to vex neuroscientists and lay people. When and why did we start having this internal narrative? How much of our day-to-day experience occurs unconsciously? What is the line between a conscious and unconscious process? These questions are still open. Perhaps Jaynes’ strange hypotheses will never play a role in answering them. But many people—readers, scientists, and philosophers alike—are grateful he tried.

Veronique Greenwood is a science writer and essayist. Her work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Discover, Aeon, New Scientist, and many more. Follow her on Twitter here.