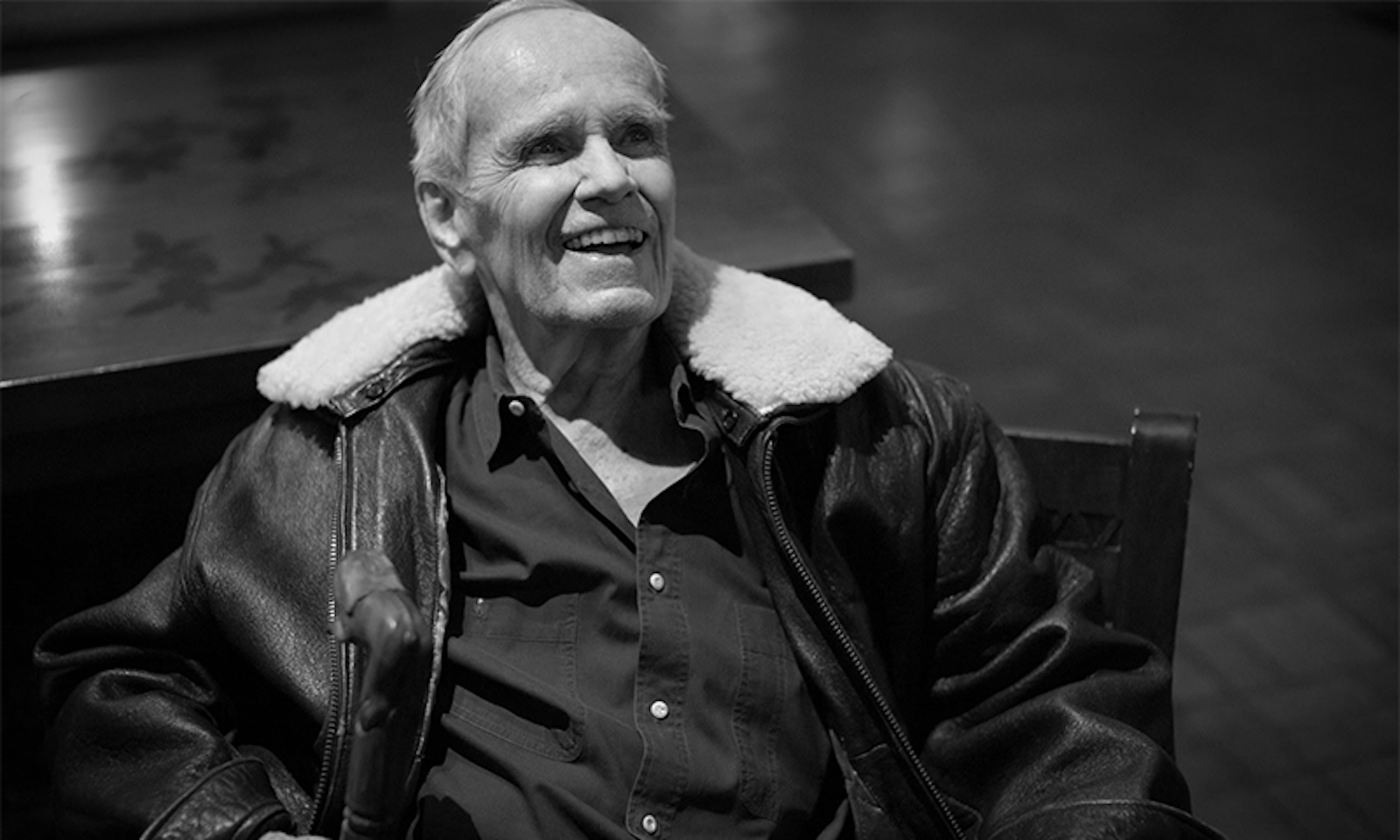

I always feel grateful that Nautilus is associated with Cormac McCarthy, who died on Tuesday at his home in Santa Fe. He was 89 years old. In 2017, the great American novelist published his first and only piece of nonfiction, “The Kekule Problem,” in Nautilus.

Since Nautilus set sail in 2013, we’ve tacked in line with the Santa Fe Institute, where brilliant minds have convened since 1984 to illuminate the complexities and connections beneath the world’s surfaces. Santa Fe Institute cofounder Murray Gell-Man, a Nobel laureate in physics, met McCarthy in 1981, when the novelist won a MacArthur Fellowship, the famous “genius” grant. The physicist learned the artist had a curiosity as boundless as the universe. At the Santa Fe Institute, McCarthy had a home away from home for 39 years.

Our print journal made its way around the Institute, where McCarthy read and admired it, we learned from the Institute’s president, David Krakauer, who has written a host of articles for us, including one last year about his friendship with McCarthy. When McCarthy wanted to publish ideas that had been cycling through his mind about language and the unconscious, he turned to Nautilus.

I was excited to publish “The Kekule Problem” because it reads in tune with McCarthy’s fiction. It’s a song to the mysteries of the unconscious, a dreamland that feeds solutions to our conscious minds, as it did when it offered the configuration of the benzene molecule to 19th century chemist August Kekule while he slept.

The idea that language is the root of thinking, that it evolved to bond humans, seemed to offend McCarthy. Language wasn’t a biological invention; it was a human invention. Let’s say language emerged 100,000 years ago, as “influential persons,” a sly McCarthy writes, say it did. That’s an eyeblink to the 2 million years “in which our unconscious has been organizing and directing our lives. And without language you will note.”

This is the artist at work. You can appreciate the language in McCarthy’s fiction for its lexical richness, gothic rhythms, and descriptive precision. In Suttree, you positively live on the grimy shore of the Tennessee River, where the “water was warm to the touch and had a granular lubricity like graphite.” Same for Blood Meridian. The Southwest desert is your home, or prison. You look up at the night sky. “All night sheetlightning quaked sourceless to the west beyond the midnight thunderheads, making a bluish day of the distant desert, the mountains on the sudden skyline stark and black and livid like a land of some other order out there whose true geology was not stone but fear.”

The artist doesn’t want you to live on the surface. McCarthy’s fiction is a portal into the unconscious where primeval feelings dwell. Language is paradoxical that way. It’s a signpost to the places where language has little say.

It might seem like another paradox to say the artist of the unconscious was deeply engaged in science, where conscious precision rules. Not so. McCarthy’s fiction captures the life force that is the very subject of science. McCarthy’s final two novels, The Passenger and Stella Maris, delve explicitly into physics and math, reflecting his decades of conversations with scientists at the Santa Fe Institute. But his microscopic eye on the natural world was always there.

In this exquisite passage from 1979’s Suttree, the narrator, on a “hushed and mazy” Sunday afternoon, lies down on a cot in his houseboat on the river: “The heart beneath the breastbone pumping. The blood on its appointed rounds. Life in small places, narrow crannies. In the leaves, the toad’s pulse. The delicate cellular warfare in a waterdrop.” That is science. And art.

“The Kekule Problem” received criticism from linguists who felt McCarthy was, in short, giving language short shrift. To me, McCarthy uses language, the remarkable human invention, to open us to the verities of life and our connection to nature before the modern world closed the doors. This has always been his theme.

In McCarthy’s 1994 novel, The Crossing, a teenage cowboy traps and becomes emotionally attached to a pregnant wolf in Mexico. The boy is briefly arrested by Mexican deputies, and the wolf is mauled by dogs when it’s chained in a pit and forced to fight. To put the wolf out of its misery, the boy shoots it in the head and carries it to the mountains to bury it. As he closes the wolf’s dead eyes, he “could see her running in the mountains, running in the starlight where the grass was wet and the sun’s coming as yet had not undone the rich matrix of creatures passed in the night before. Deer and hare and dove and groundvole all richly empaneled on the air for her delight, all nations of the possible world ordained by God of which she was one among and not separate from.” ![]()

Kevin Berger is the editor of Nautilus.

Lead photo: Cormac McCarthy at Santa Fe’s La Fonda Hotel in 2023. Credit: Kate Joyce.