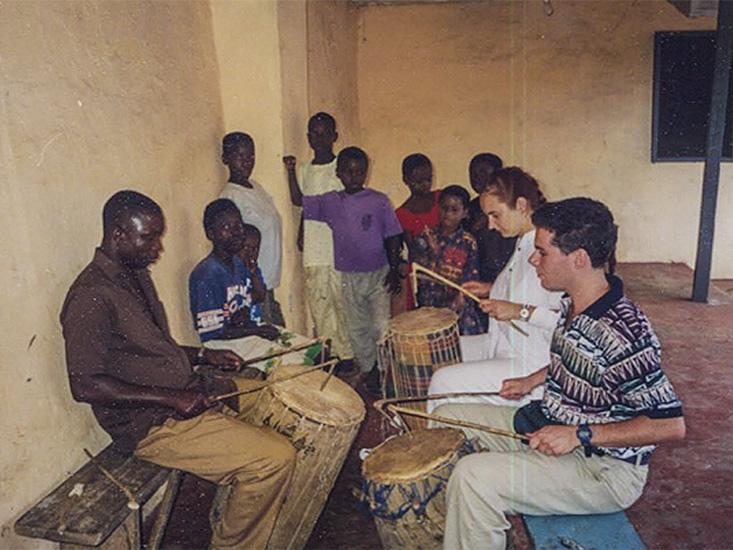

My wife Ingrid and I had been in Aburi, Ghana for just over a week when our host, Kwame Obeng, informed me that I’d be joining the royal drummers for a performance at the chief’s palace the following afternoon, in celebration of an important holy day.

It’s not as if I was unprepared. I’d first met Obeng three years earlier, when he came to Toronto to coach a drumming troupe made up of Ghanaian immigrants and a lone Westerner (myself). We became close: Obeng called me mi nua, or “my brother,” in Twi, the language of his ethnic group, the Akan. And when his visa expired after a year, he invited me to continue studying with him back home in Aburi, a small town nestled in the verdant Akuapem Hills. Two years later, I took him up on his invitation. And now it was time to show him what I could do. What happened next was a complete surprise to me. I would never find out if it was a surprise to Obeng.

The day of the performance, Obeng stationed me and his nephew, a young man named Kwame Antwi, at a pair of enormous, barrel-shaped bommaa drums standing side by side. Each bommaa was carved from a 5-foot length of hollowed-out tree trunk, and both were painted a lustrous black and wrapped in red velvet fastened with brass studs. Just in front of us and to our left, Obeng himself stood before a pair of massive, goblet-shaped atumpan drums with antelope-skin heads. Directly behind us, a quartet of young boys and middle-aged men played three smaller drums and an iron bell. They were the rhythm section, while the two Kwames and I formed the front line.

I had no choice but to soldier on at the drums. While I did, I also struggled to comprehend what was happening.

As the performance began, Kwame Antwi and I began bashing away at the thick cowhide heads with long, L-shaped sticks fashioned from tree branches. We made quite a pair: him long and lean and dark, me short and soft and very, very white. The raised platform at the opposite end of the courtyard gradually filled with chiefs and palace officials draped in togas and dresses, all in different colors: turquoise, scarlet, cobalt, maroon. There was very little chitchat. Instead, our audience listened in silence as we played the drums, and various notables got up to make speeches and offer prayers to their ancestors.

The rhythms played on the big bommaa drums consist of several sets of patterns that are executed in unison by both drummers, each one longer and more complicated than the last. At first, I was able to match Antwi stroke for stroke. But as we moved into the longer and more complex material, things went completely off the rails. Suddenly, Antwi seemed to be adding rhythms that I’d never heard before. I tried to keep up with him, to imitate his hand movements even if I couldn’t quite make out what he was playing.

But I couldn’t. Standing there in front of the assembled royals, the truth slowly dawned on me: The rhythms I was supposed to play in public in Aburi were not the same as the ones that Obeng had taught me in Toronto, and which he had repeated for Ingrid and me during a brief private lesson just the previous day. Instead, they included swathes of material that were radically different from anything he’d shown us thus far; so different that I couldn’t figure them out, let alone execute them, in the heat of the moment. But no one else seemed willing to admit it.

“Alex, what is wrong?” Antwi asked as the two of us sat down next to Ingrid during a break. “You played these yesterday, no problem.”

“The rhythms are different,” I said, still in shock at having totally blown my public debut.

“What?”

“These rhythms are different. They aren’t the ones I played in Toronto. They aren’t the ones we played with Obeng in our lesson yesterday.”

“Of course they are the same,” said Antwi. “Only faster!”

That would be the standard line from our Ghanaian friends for the next several months: The rhythms are the same, only faster! But they weren’t. As our hosts continued to insist that they had taught me the correct rhythms, I flubbed performance after performance: at rituals, at funerals, sometimes for enormous crowds. I couldn’t stop performing—we’d traveled thousands of miles to learn this music, and our presence in the ensemble was a source of prestige for Obeng—but the chiefs and palace officials who knew fontomfrom best must surely have realized that I was perpetually botching it, even if they were unfailingly polite, saying only “woaye ade!” (“well done!”) after every attempt.

I had no choice but to soldier on at the drums. While I did, I also struggled to comprehend what was happening. Eventually I boiled it down to two choices: Either we had radically divergent ideas about what constituted musical sameness and difference, about what gave a piece of music its unique identity and aural signature; or Obeng was intentionally hiding the full rhythms from Ingrid and me for unknown reasons. Was it deception or mental disconnect?

My confusion—and my sudden incompetence—would not have been such a big deal if the style of music we were playing, called fontomfrom, were just background music, the Akan equivalent of cocktail piano. But it wasn’t. Every time chiefs appeared in public on official business, the royal drums came out. They were a vital element of regalia, a principal accoutrement of office. Perhaps even more importantly, the big bommaa and atumpan drums didn’t just make music for dancing. They talked. Literally.

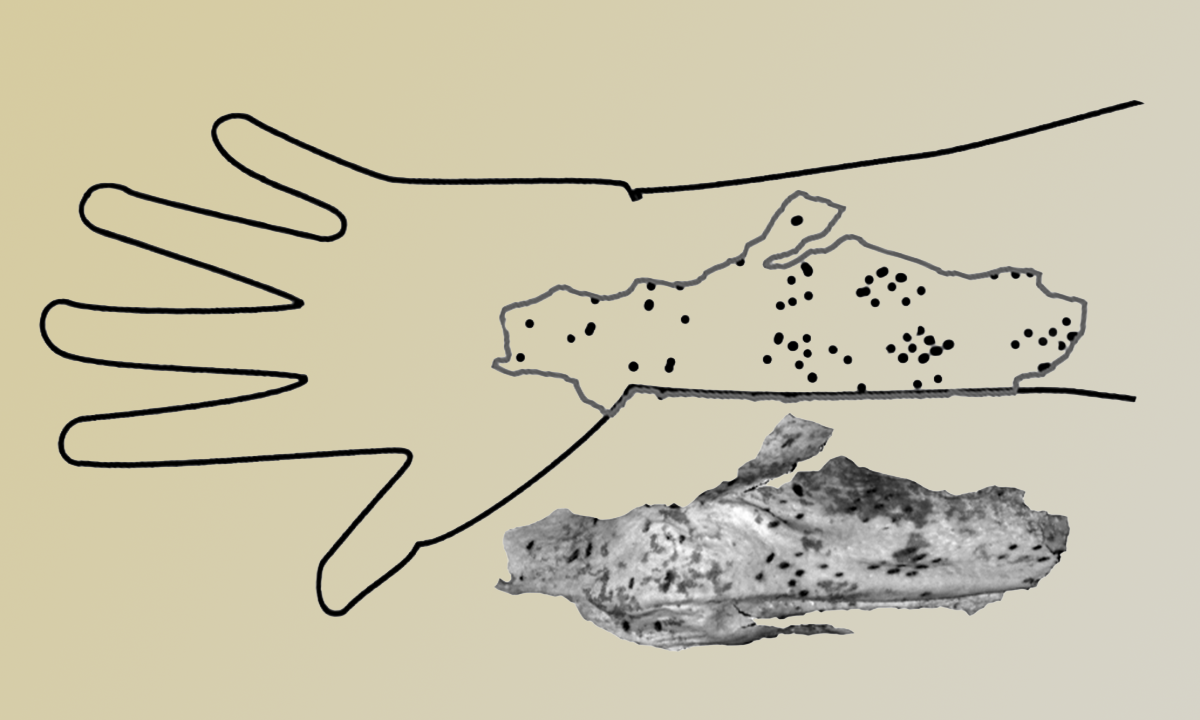

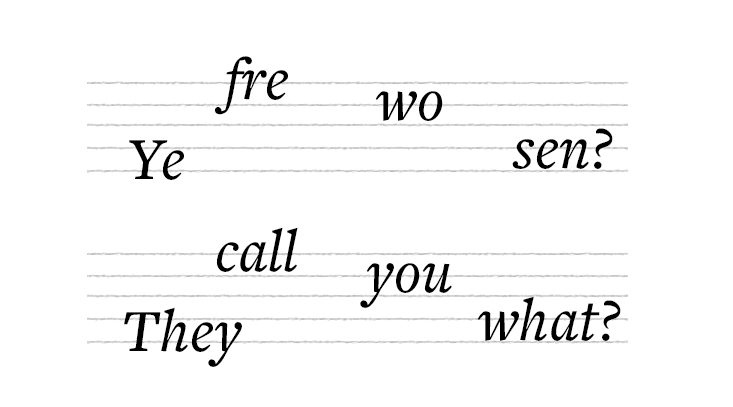

Twi is a tone language, like Mandarin Chinese: Each syllable has its own pitch, each word or phrase its own unique melody. Change those tones, alter those melodies, and the meaning of the words changes, too. Something as simple as asking a person’s name becomes an exercise in birdsong.

By imitating the tones and rhythms of Twi, the Akan can “speak” with their musical instruments—their horns and trumpets, their drums and bells—almost as clearly as they do with their mouths. The atumpan, which produce two distinct pitches, are particularly well suited to this task; but the bommaa can do it, too. That was why the crowd at the palace had been so quiet: They were listening to what the drums had to say. The phenomenon, widespread in both West and Central Africa, is known as surrogate speech. It can add a layer of semantic depth to even the simplest music.

Every time that the chief, Nana Djan Kwasi, got up and walked around the courtyard, for instance, the two Kwames and I engaged in a little call-and-response.

Kwame Obeng: bom bom

Kwame Antwi and me: BRRM BRRM!

The rhythmic phrase bom bom BRRM BRRM, bom bom BRRM BRRM had a nice beat to it, and could just have been pleasant filler, something to play while the chief moved from place to place. And on one level, it was. On another, though, it was an earnest plea from the principal talking drums in the ensemble: Nana, bre bre! Nana, bre bre! “Chief, slowly! Chief, carefully!” If a chief stumbles in public, it’s a sign of bad luck. So we were asking him to watch his step.

The drums didn’t just speak to the living, but also to the dead: the revered ancestors who have left this earthly plane, yet continue to influence the affairs of their kin. The Akan believe that their ancestors are forever watching over them, and must forever be placated with prayers, offerings, and other remembrances. They also believe that their ancestors are particularly sensitive to the sound of the drums. That’s one of the reasons why Akan drummers normally take great care to avoid mistakes. You wouldn’t want to anger your ancestors by saying the wrong thing. In the old days, a sloppy royal drummer was likely to have an ear cut off. So when I butchered my part alongside Antwi that day at the palace, I wasn’t just making the group sound bad—I was sticking a wrench in the gears of a rich cultural system where speech, art, and religion are all intertwined. Little wonder my heart was pounding in my ears as I walked away from the drums, the echoes of my mistakes still ringing through the courtyard.

This music was important. Why, then, did Obeng insist on withholding information that would have prevented us from blowing almost every performance we gave while we were in Ghana? Did he have some ulterior motive? Or was there some basic aspect of Akan music that rendered it opaque to us on a fundamental level—culturally, psychologically, or even neurologically?

Ingrid and I were both graduate students at the University of Illinois before we left for Ghana in the summer of 1997. I was a Ph.D. candidate in ethnomusicology, a kind of musical anthropology, and Ingrid was completing a doctorate in percussion. In other words, we weren’t exactly musical hacks. But the difficulty of fontomfrom was unexpected, and exceptional.

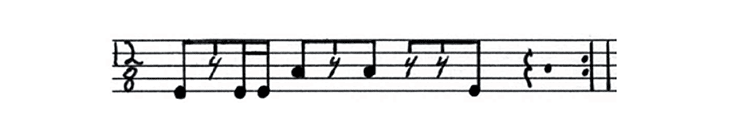

Unlike the drumming that often accompanies African dance classes in the West, fontomfrom doesn’t have a particularly strong groove. But like most West African drumming, it does contain many different moving parts, from the long, complex patterns played on the bommaa and atumpan to the short, highly repetitive patterns played on the smaller drums and the iron bell. All of these rhythms interlock; often, they complete one another, the sounds of one drum filling in the silences of the others to produce unexpected patterns, like individual strands in a tapestry.

Fontomfrom rhythms can also be curiously ambiguous. For instance, you might think you’re playing a waltz (ONE two three, ONE two three), while the guy next to you sounds as if he’s playing a march (ONE two, ONE two). In fact, if you listen to him long enough, you might change your mind and decide that you, too, are really playing a march. In that sense, playing in a fontomfrom ensemble is like being inside a sonic version of an Escher lithograph: As you shift your attention from one part to another, the entire picture seems to change.

Attempting to decipher those brief, puzzling segments was like trying to catch a falling knife.

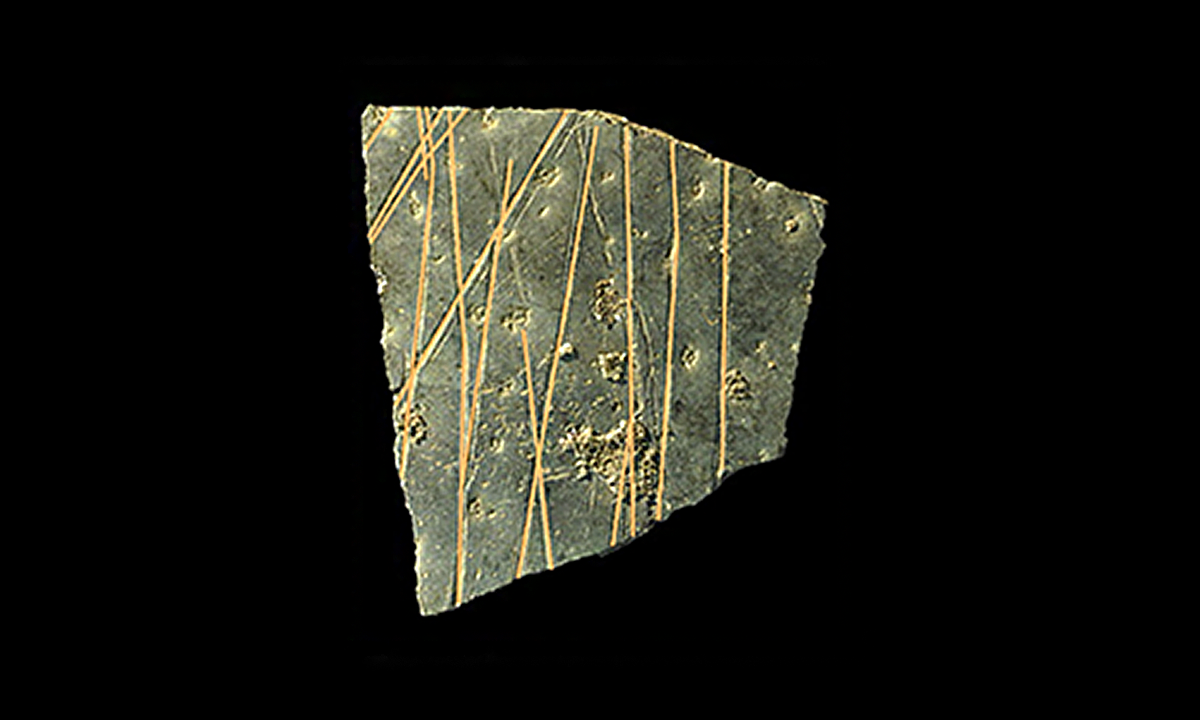

The bommaa patterns that I was suddenly expected to play in Ghana, however, were in a league of their own. Bits of them weren’t just rhythmically ambiguous; they were rhythmically dysfunctional. A musicologist would say they were ametric, or lacked a clear relationship to any kind of steady pulse whatsoever. But there was definitely some kind of logic to them, because whenever two drummers who actually knew what they were doing took over at the bommaa, they not only managed to play in perfect unison; they also coordinated their entrances and exits against the matrix of the other drummers’ parts with flawless consistency. Clearly, they knew—and heard—something we didn’t.

It didn’t help that Ingrid and I could barely hear the bommaa rhythms at all. While we were usually paired with an experienced court drummer in performance, we were also constantly being told to play “louder,” “faster,” and “with more force,” which only made it harder for us to make out the rhythms that our partners were playing (and easier for everyone else to hear our mistakes). Not that it would have been easy under other circumstances: It is hard to describe just how loud a fontomfrom ensemble is, with its clangorous iron bell, its piercing small drums, its booming atumpan, and its thunderous bommaa. To make matters worse, Nana Djan Kwasi’s palace courtyard was an enormous echo chamber. We taped every performance we gave at court, but the sound of the big drums ricocheting around the concrete walls and corrugated metal roof completely overloaded our microphones, turning all of our recordings into a howling mess.

Toward the end of our stay, a friendly sub-chief at the court of Nana Djan Kwasi allowed us to record Obeng and the rest of the royal drummers under more controlled conditions in a nearby village. With the help of these tapes, Ingrid nearly got the rhythm down. She was able to sing long stretches of it under her breath as she listened along: “Da da, da da, da DA da da DA ...”

“Hey, Al, it’s actually starting to make sense! “I can follow along with most of it now.”

“Me, too,” I said. “But there are a few places where they still lose me.”

“You mean like here?” Ingrid said, cueing up a segment of the tape for me.

“Yeah,” I said, squinting slightly. “What the hell is that?”

Western music has evolved in concert with its own notation system, so that Western musicians tend to hear what they can read, and read what they can hear. It did not evolve to reflect the rhythmic subtleties of fontomfrom. There were, we discovered, brief snippets of those bommaa rhythms that we could not notate accurately; as far as our musical system was concerned, they did not exist. Perhaps as a consequence, we couldn’t quite hear them, either: They sounded blurry, like figures in an Impressionist landscape. The problem was almost certainly not with our ears, but with our brains.

Bill Thompson, a psychologist at Macquarie University in Australia who specializes in music perception and cognition (and whom I once served as a graduate assistant at York University in Toronto), suggests that we may have lacked a mental template, or schema, for categorizing these rhythms, and were therefore unable to perceive them clearly. “Rhythm is an interesting case,” Bill told me, “because my sense is that the capacity to ‘hear’ a particular rhythmic pattern is first and foremost equivalent to the ability to ‘predict’ what will come next at varying time spans.” In the absence of such a schema, Bill adds, “we cannot predict what will come next, and have the experience of ‘not being able to hear the rhythm.’ Of course we ‘hear’ the rhythm in a literal sense, but we just can’t predict the unfolding pattern.” The ethnomusicologist David Locke, a specialist in West African drumming at Tufts University, experienced something similar when studying a form of fontomfrom played by an ethnic group known as the Ga. Echoing Thompson, he believes that a “lack of organizing features of mind” can make it “hard to even perceive what the ears are receiving.”

Whatever the reason, attempting to decipher those brief, puzzling segments was like trying to catch a falling knife. I can still remember the sense of shock I felt when I realized that I was experiencing the aural equivalent of a blind spot. It was as if a highly selective stroke had robbed me of the ability to read the letter Z or see the color purple. Those rhythms, some of them passing in the blink of an eye, were literally beyond my ken.

So it may not have mattered whether Obeng had taught us everything we needed to know; I doubt we could have played it even if he had. But the question remained: Why didn’t Obeng acknowledge that the patterns he taught us in private were not the rhythms we were expected to play in public?

After some effort, Ingrid and I managed to persuade Kwame Antwi, my partner at the big bommaa drums, to teach us the extended patterns that we were supposed to play during public performances—the ones that Kwame Obeng refused to admit even existed, and that I couldn’t mimic, no matter how hard I tried. But the experience only left us more confused than ever. Rather than playing what we so dearly wanted to hear, or even running through what Ingrid called the “ridiculous baby-version” of the bommaa rhythms that Obeng insisted on showing us in our lessons, Antwi played yet another simplified variation of them. Antwi’s lesson-version was slightly more complicated than Obeng’s, but still nothing like the real deal. Yet when I said as much, Antwi steadfastly maintained his innocence.

“Yes, it is the same,” he said.

“It doesn’t sound the same. And it isn’t what Kwame Obeng shows us in our lessons with him, either,” I said.

“Yes, they are the same!” he insisted.

“The same as what?” I wanted to scream.

Maybe the problem was the surrogate speech function of fontomfrom. What if those elusive rhythms had no semantic content, so that Obeng and Antwi didn’t consider their absence (or presence) to constitute a meaningful difference? That might render the “lesson patterns” and the “performance patterns” equivalent to our teachers, even if they seemed like obviously distinct entities to us. Or perhaps the two Kwames evaluated musical identity according to some other criteria altogether—criteria that were as foreign to us as the mystery rhythms themselves.

I thought that I’d been tapping out some harmless dance rhythms, when in fact I had been participating in a brief audio play about the ritual slaughter of children.

Desperate for insight, Ingrid and I turned to J.H.K. Nketia, a renowned ethnomusicologist who was then director of the International Center for African Music and Dance at the University of Ghana. Nketia was my hero: An Akan from the Ashanti region, he did fieldwork in Akuapem in the 1950s, and wrote the seminal work on Akan drumming. He didn’t so much as blink an eye when we told him about the simplified bommaa rhythms that Obeng and Antwi tried to pass off as the real thing in our lessons. But he did smile a bit.

“They may be simplified, but they are still the same,” he said.

“Because they share certain rhythmic motifs?” Ingrid asked.

“Yes, there is that. But not just that,” he said. “A piece consists of a number of different elements that lend it identity. If those elements are present, it is the same. If not, it is different. This is a concept you will have to struggle with.”

But which elements make up a rhythm’s identity? When Obeng came to Toronto, he taught me and my fellow drummers both basic and alternate versions of the accompanying patterns played on the smaller instruments, spelling the differences out clearly. In Aburi, however, Obeng didn’t even acknowledge the differences between the basic bommaa rhythms we learned in our lessons—rhythms he had previously taught me in Toronto, and that I had performed at events in Canada and the United States—and the lengthier and more complex ones we were supposed to play in public. If I knew what Obeng was paying attention to in each example, maybe I could understand the stark differences between them. But I didn’t know, and maybe, given the sheer difficulty of recognizing fontomfrom rhythms to begin with, I couldn’t.

Or, maybe our teachers were just screwing with us.

Many African societies shroud their traditional lore in secrecy, and the guardians of those secrets—elders, priests, chiefs—often reveal them gradually, divulging them in bits and pieces as a person ascends through ever higher levels of trust. This can be because the information itself is inherently sensitive, and also because its esoteric nature lends power and prestige to those who possess it. “Studies of secrecy in Africa show that the content of a secret there is less important than the use of secrecy as a strategy,” the art historian Mary H. Nooter (now Mary Nooter Roberts) wrote in her book Secrecy: African Art That Conceals and Reveals. “Although the content of a secret may be guarded and concealed, the secret’s existence is often flaunted. To own secret knowledge, and to show that one does, is a form of power.”

Could that describe how musical knowledge was treated in Akuapem? Perhaps Obeng was unwilling to teach us the missing rhythms because they constituted some kind of privileged information. And maybe their status as an open secret—one that he and the other court drummers would play in public, but that we were not allowed to learn in private—served to highlight his own authority, and our own status as neophytes.

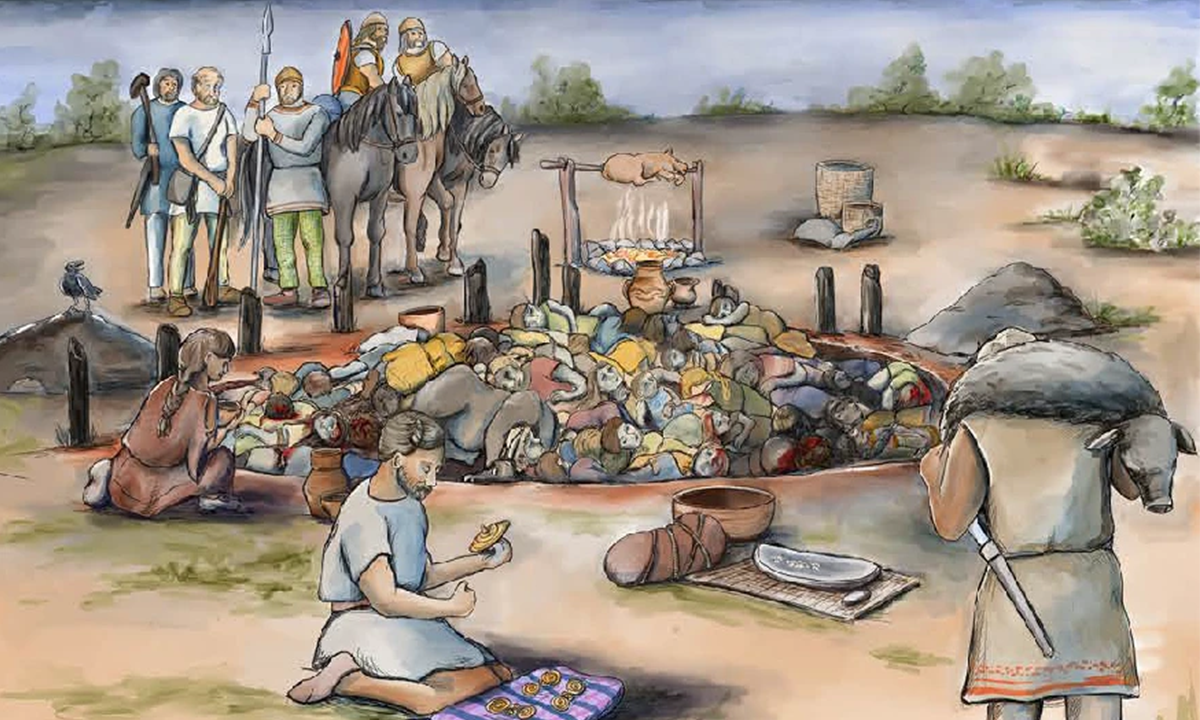

We had already experienced this dynamic of concealment and revelation first-hand. During our time together in Toronto, Obeng had never so much as mentioned to me that the smaller instruments in the fontomfrom “spoke” just like their larger cousins. Then, one day in Aburi, when Ingrid and I were at the palace helping Obeng move the fontomfrom drums around, he casually revealed what the iron bell and the three small drums were saying. It was a full-blown conversation:

Wanko a wobeko.

Woto, wobeto.

Wawie moframma kum?

Pren pren, pren pren.

“You will go even if you don’t wish to go.”

“You fall, you will fall.”

“Have you killed the little children?”

“Just now, just now.”

“What does it mean?” Ingrid asked. “Why were they killing the children?”

“It is about the old days, when the ancestors made ‘medicine,’ ” Obeng said. He went on to describe how human beings were once sacrificed at the palace, something I’d previously only read about in anthropological studies and historical texts. Needless to say, we were both taken aback—especially me. For several years, I thought that I’d been tapping out some harmless dance rhythms, when in fact I had been participating in a brief audio play about the ritual slaughter of children.

I don’t know why Kwame Obeng chose that particular moment to enlighten us, but I doubt it was happenstance. Perhaps, unbeknownst to us, Ingrid and I had somehow demonstrated our worthiness.

Another time, at a funeral, I asked Kwame Antwi if the small ornament that he and many others wore on the straps of their sandals meant anything.

“Yes,” he said.

“What?” I asked.

“Aburuburuw nkosua,” he said. “It is the name of a bird’s egg.”

“Is that some kind of proverb?”

“Yes.”

“What does it mean?”

“I do not know. We will have to ask Kwame Obeng.”

So we did.

Obeng responded in Twi: “If it is written, it is written; if it is God’s will, then it will happen.”

I turned back to Antwi.

“Does everyone know what these ornaments are called?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said.

“But do they know what it means?”

“No. Very few know that; only those who move with the royals.”

Antwi was Obeng’s nephew and his lieutenant in the palace ensemble. By any reasonable standard, he spent a lot of time moving with the royals. But even he didn’t know something as basic as the meaning of a proverb that was literally stuck to his feet most of the time.

Did the missing complexities in the music represent my own mysterious proverb, something I had not yet earned the right to learn? Was this all part of the process, by which I could only demonstrate my worth by figuring out the music on my own? Or was Obeng reluctant to teach me the missing rhythms for other reasons, yet equally reluctant to explicitly turn me down?

That’s as far as I got. Eighteen years later, the reasons for Obeng’s behavior remain as inscrutable to me in hindsight as those puzzling bommaa rhythms proved to be when I first encountered them.

And that is a lesson in itself.

As a musician and an ethnomusicologist, I assumed that with enough time and effort, I’d eventually grok both the music and the musical behavior of our hosts. In a way, I had to believe this; doing so was central to my own sense of identity, as it probably would be to anyone doing fieldwork in cultural anthropology. Certainly, none of my mentors in graduate school had raised the possibility that I (or anyone else, for that matter) might be confronted by a group of people whose music and motives would prove so stubbornly resistant to analysis and explication. In this age of extreme interconnectedness, when once-remote lands are only a cheap flight or a webpage away, it is tempting to think that all barriers to cross-cultural understanding are gradually disappearing; that there are no longer such things as strangers, just people we have not yet Googled or seen on the Discovery Channel.

This is an illusion. Make no mistake: There are plenty of people, living in plenty of places, who remain giant puzzles to us, cheap airfare or no. And that is by no means a bad thing. Quite the opposite—it is a testament to the range of human diversity, and to the limits of human understanding. My experiences in Aburi may have been frustrating, but I learned a lot. I no longer assume that all barriers to cross-cultural communication can be overcome. Nor do I assume that I can really, truly get into someone else’s head and see (or hear) the world as they do by sheer force of reason and will—including my own friends and family.

For these reasons, and also for the sheer intensity of our time there—we witnessed animal sacrifice and spirit possession, encountered cultural riches and material poverty rarely seen in the West, and suffered radical culture shock of a sort neither of us had experienced before, and haven’t again since—Aburi still fills me with a sense of awe. And I know that Ingrid feels the same way. When we talk about the things that shaped us as individuals and as a couple, we always return to Ghana, and the mystery of those bommaa rhythms.

Alexander Gelfand is a freelance writer and recovering ethnomusicologist based in New York City. He is working on a memoir of his time in Ghana.