Stone steps descended into the ground, and I walked down them slowly as if I were entering a dark movie theater, careful not to stumble and disrupt the silence. Once my eyes adjusted to the faint light at the foot of the stairs, I saw that I was standing in the open chamber of a cave.

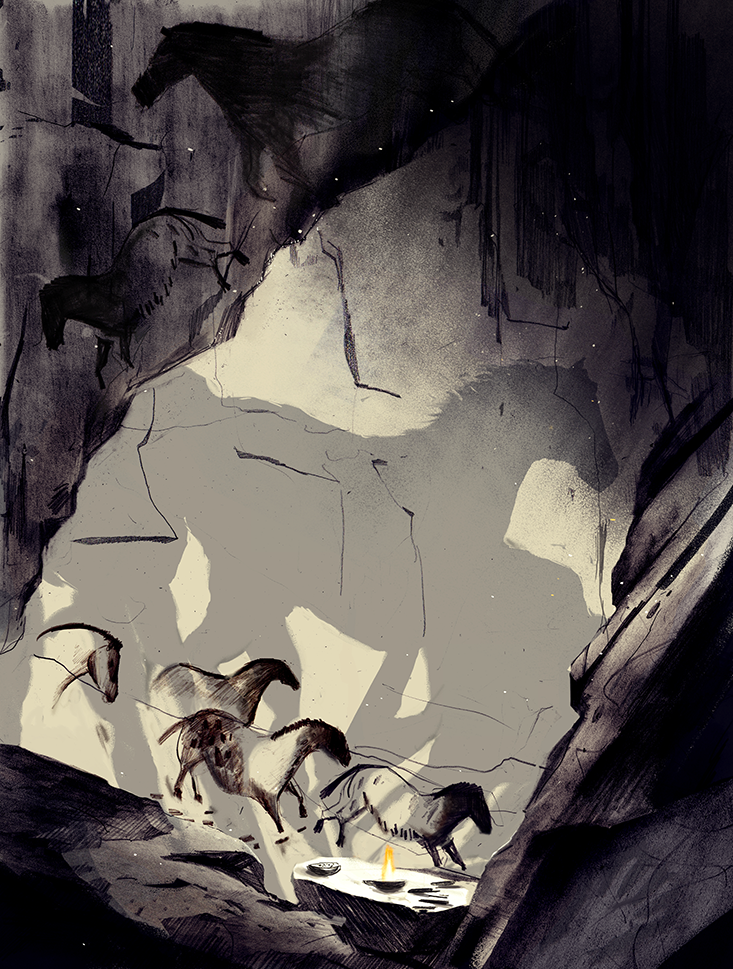

Where the limestone wall arched into the ceiling was a line of paintings and drawings of animals running deeper into the cave. The closest image resembled a bison, with elongated horns and U-shaped markings on its side. The bison followed several horses painted solid black like silhouettes; above them was an earthy-red horse with a black head and mane. In front of that was a very large bison head that was completely out of scale with respect to the other images.

It was the summer of 1995, and in the dim glow, I gazed at the ghostly parade just as my ancestors did roughly 21,000 years ago. Radiocarbon dates from Lascaux cave suggest the art is from that period, a time when wooly mammoths still roamed across Europe and people survived by hunting them and other large game. I stood in silence as I tried to decode the work of the ancient people who had come here to express something of their world.

When Lascaux cave was discovered in 1940, more than 100 small stone lamps that once burned grease from rendered animal fat were found throughout its chambers. Unfortunately, no one recorded where the lamps had been placed in the cave. At the time, archeologists did not consider how the brightness and the location of lights altered how the paintings would have been viewed. In general, archeologists have paid considerably less attention to how the use of fire for light affected the development of our species, compared to the use of fire for warmth and cooking. But now in Lascaux and other caves across the region, that’s changing.

Artists at Lascaux used fire to see inside caves, but the glow and flicker of flames may also have been integral to the stories the paintings told. “Today, when you light the whole cave, it is very stupid because you kill the staging,” says Jean-Michel Geneste, Lascaux’s curator, the director of France’s National Center of Prehistory, and the head of the archaeological project I worked on that summer. Worse yet, most people only see cave paintings in cropped photographs that are evenly lit with lights that are strong and white. According to Geneste, this removes the images from the context of the story they were meant to tell and makes the colors in the paintings colder, or bluer, than Paleolithic people would have seen them.

Reconstructions of the original grease lamps produce a circle of light about 10 feet in diameter, which is not much larger than many images in the cave. Geneste believes that early artists used this small area of light as a story-telling device. “It is very important: the presence of the darkness, the spot of yellow light, and inside it one, two, three animals, no more,” Geneste says. “That’s a tool in a narrative structure,” he explains. Just as a sentence generally describes a single idea, the light from a grease lamp would illuminate a single part of a story. Whatever tales may have been told inside Lascaux have been lost to history, but it is easy to imagine a person moving their fire-lit lamp along the walls as they unraveled a story step-by-step, using the darkness as a frame for the images inside a small circle of firelight.

Geneste supports his hypothesis by pointing to the various sizes of animals. “If you want to have several animals in a narrative relationship it is necessary to have them small,” he says. “If you want only one animal, you make them big.” If Geneste is right, the paintings I saw in the Hall of Bulls could have been read like a comic strip, as a series of frames: first the bison, then two black horses, more horses, a focus on the bison, and so on down the length of the chamber.

“When you light the whole cave, it is very stupid because you kill the staging.”

What’s more, a flickering flame in the cave may have conjured impressions of motion like a strobe light in a dark club. In low light, human vision degrades, and that can lead to the perception of movement even when all is still, says Susana Martinez-Conde, the director of the Laboratory of Visual Neuroscience at the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix, Ariz. The trick may occur at two levels; one when the eye processes a dimly lit scene, and the second when the brain makes sense of that limited, flickering information.

Physiologically, our eyes undergo a switch when we slip into darkness. In bright light, eyes primarily rely on the color-sensitive cells in our retinas called cones, but in low light the cones don’t have enough photons to work with and cells that sense black and white gradients, called rods, take over. That’s why in low light, colors fade, shadows become harder to distinguish from actual objects, and the soft boundaries between things disappear. Images straight ahead of us look out of focus, as if they were seen in our peripheral vision. The end result for early humans who viewed cave paintings by firelight might have been that a deer with multiple heads, for example, resembled a single, animated beast. A few rather sophisticated artistic techniques enhance that impression. One is found beyond the Hall of Bulls, where the cave narrows into a long passage called the Nave.

High on the Nave’s right wall, an early artist had used charcoal to draw a row of five deer heads. The images are almost identical, but each is positioned at a slightly different angle. Viewed one at a time with a small circle of light moving right to left, the images seem to illustrate a single deer raising and lowering its head as in a short flipbook animation.

Marc Azéma, a Paleolithic researcher and filmmaker at the University of Toulouse in France, has studied dozens of examples of ancient images that were meant to imply motion and has found two primary techniques that Paleolithic artists used to do this. The first is juxtaposition of successive images—the technique used for the deer head—and the second is called superimposition. Rather than appearing in sequence, variations of an image pile on top of one another in superimposition to lend a sense of motion. Superimposition can be seen in caves across France and Spain, but some of the oldest examples come from Chauvet cave in France’s Ardèche region. Burned wood and charcoal streaks along Chauvet’s walls indicate that campfires and pine torches lit the cave.

At 32,000 years old, the oldest paintings at Chauvet cave are about 10,000 years older than those at Lascaux, but they are no less accomplished. One of the most extensive images in the cave is the “Grand Panneau,” a large panel that shows lions, rhinoceroses, bison, horses, and a wooly mammoth. Azéma explains that the panel may relate two separate narratives of lions stalking prey. Near the center of the panel is a charcoal drawing of a rhinoceros that seems to have seven or eight horns, as well as several backs. The rhinos look as if they are piled on top of one another, but Azéma has teased apart each section of the image to show that it could in fact be one rhino in varied positions. In this superimposition, he says, the rhino raises and lowers its horn. Azéma refers to these images as the beginning of cinema because they depict both narrative and motion.

During my visit, the light inside Lascaux shined steady and just strong enough for me to make out the colors in the rock walls and the paintings. We were only permitted to stay for about 20 minutes, which was enough time to see all the images except for a few that are difficult to reach. Preserving the artwork there has been a constant battle. Intermittently since 2001, Lascaux has been closed due to infestations of molds and fungus that threaten many of the paintings. One type of black mold even seems to feed on the light that people bring into the cave.

I had stood in the Nave with barely enough room to turn around without brushing against the walls. Looking at the art felt like reading a partially translated language. The shapes of the animals were familiar, but their meaning was obscured by the distance between my mind and those of 21,000 years ago. Paleolithic art may have been spiritual—prayers for a successful hunt—or maybe they related specific events—the time when a pride of lions hunted a large rhinoceros. Or perhaps it was like modern-day art, and fulfilled a variety of roles that aren’t easily put into categories. Even though the images were mostly of animals, what the art conveyed to me was humanness. The images were an attempt to express a reaction to a dynamic environment. Now that we live in a halogen and LED lit world, it’s easy to forget that the way we illuminate the world affects how we see it.

Zach Zorich is a freelance science journalist and contributing editor at Archaeology magazine.