Images and videos usually serve as the most concrete, the most unarguable, and the most honest evidence of experiences and events we cannot witness ourselves. This is often the case in court, in the news, in scientific research, and in our daily lives. We trust images much more deeply and instinctively than we do words. Words, we know, can lie. But that trust makes it all the more shocking—and serious—when images lie to us, too.

Photoshop isn’t entirely to blame. Doctoring photographs long predates software—Mussolini famously had his horse handler removed from a photograph taken in 1942 so it would appear he was able to control the horse himself—but software certainly makes altering images easier, cheaper, faster, more convincing, and much more widespread than ever before. (Thankfully, most alterations are done out vanity—though even some of these can stir up considerable controversy. In 2014, for example, the website Jezebel offered a $10,000 reward to anyone who would provide it with unretouched photographs of Lena Dunham taken for Vogue.)

But beyond the world of glossy magazines and personal Instagram feeds, the authenticity of individual photographs can have much higher stakes—high enough for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), for instance, to announce, last year, that it was launching a Media Forensics program. It’ll fund new tools and techniques to, in the words of the DARPA description, “level the digital imagery playing field.” Those tools and techniques will likely prove useful to more areas than just national security.

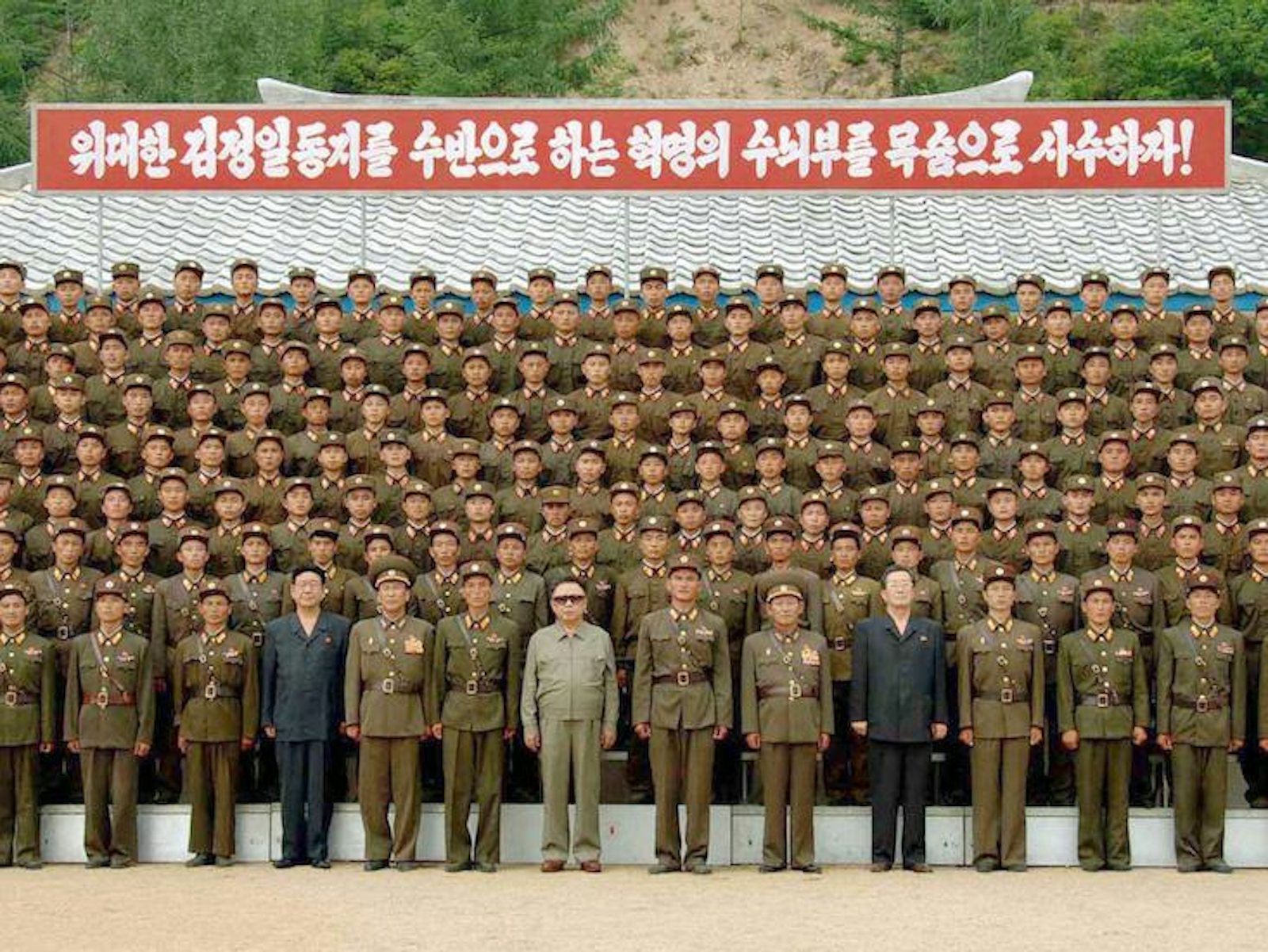

Scientists, for example, aren’t immune to the temptation to doctor imagery. An editor of one biology journal estimated that one fifth of the images submitted to the journal for publication had been manipulated inappropriately, according to a 2005 article in Nature. Image manipulation can also have consequences in the arenas of politics and business. In 2008, the North Korean Central News Agency released a photograph of Kim Jong-il posing with military officers that many believed had been doctored to dispel rumors that he was sick or dead. In 2011, in the middle of a lawsuit between Apple and Samsung Electronics over intellectual property infringement, Apple was accused of resizing images of the Galaxy S smartphone and Galaxy Tab tablet in court filings to make those devices more closely resemble Apple’s iPhone and iPad.

It may come as a surprise that, even though we’re aware that photographs can—and are—being manipulated, the technology for manipulating images is nonetheless improving so rapidly that it seems we’re actually getting worse at detecting altered or fake photographs.

In a 2016 paper, Hany Farid, a computer scientist at Dartmouth, along with some colleagues, found that “observers have considerable difficulty” telling computer-generated and real images apart—“more difficulty than we observed five years ago.” On the bright side, though, when the researchers provided 250 Mechanical Turk participants with a brief “training session”—by showing them 10 labeled computer-generated images and ten original photographs—their ability to distinguish between the two types of images improved significantly.

That’s encouraging, because manipulated or fabricated images can do serious damage to our sense of the past. Take, for instance, a 2007 paper titled “Changing history: doctored photographs affect memory for past public events.” The researchers showed participants, young and old, either an original or a doctored photograph of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests in Beijing or a 2003 protest in Rome against the war in Iraq. The manipulated images distorted the memories of the pictured events for those who saw them. They “remembered” the Tiananmen Square protests as being larger, and protests in Rome as being more violent—more property damage and injuries—than those who saw the unaltered images. The ones exposed to the doctored images even indicated they would be less likely to participate in protests in the future.

Other studies have since confirmed the power fake or misleading imagery has over us. For example, “Photographs can distort memory for the news,” and “Photographs cause false memories for the news.” And, over the past decade, as image manipulation software has become increasingly widespread and easy-to-use, the tools for detecting these manipulations have not kept pace, even though these effects make it abundantly clear how important it is to be able to reliably authenticate photos.

Farid has spent years trying to do that. In 2011, he co-founded Fourandsix Technologies, an image authentication service, to develop techniques to identify the fakes. He’s also trying to make these detection methods nearly as ubiquitous and accessible as the image-manipulation tools themselves by, for example, providing easy-to-use image forensics tests to customers. These tests range from analyzing the position and shape of people’s irises in photographs to whether or not the sources of light in a photograph are consistent for the entire image. Another approach is to look for the distinctive “fingerprint” of a digital camera—the unique digital markers it leaves on the image files it creates—in order to verify that an image was actually produced by a camera, rather than generated by computer.

No doubt these new methods for identifying altered images are important for digital forensics. But until the day comes when forensic image analysis is done entirely automatically, by an app, say, perhaps the answer to the modern influx of image manipulation software lies in training our own eyes to be a little less trusting, and a little more discerning. That more skeptical lens on the world is increasingly necessary.

Josephine Wolff is an assistant professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

Watch: Mario Livio, an astrophysicist who helped determine the universe’s rate of expansion, explains how the Hubble Telescope has changed the way we see the cosmos.