If you see a car along that road,” Tyler Nordgren warned me, “don’t look at the headlights. It’ll ruin your night vision for 2 hours.” Nordgren and I had pitched our tents under the brow of Mount Whitney in the Alabama Hills, a field of boulders near Death Valley. We watched it get dark, and in the nighttime horizon, the sky was perforated by stars and streaked by the Milky Way. Or, to put it in approximate scientific terms, it was probably a 3 on the Bortle Scale, the 9-level numeric metric of night sky brightness.

Even so, we could still see domes of hazy light from 200-odd miles south in Los Angeles and 250 miles east in Las Vegas. That encroaching urban glow was like highlighter calling attention to the issue that Nordgren, a prophet whose cause is light pollution, wanted to illustrate for me.

“We’re losing the stars,” the 45-year-old astronomer told me. “Think about it this way: For 4.5 billion years, Earth has been a planet with a day and a night. Since the electric light bulb was invented, we’ve progressively lit up the night, and have gotten rid of it. Now 99 percent of the population lives under skies filled with light pollution.”

Nordgren is an affable, engaging, and quotable Cassandra, an enthusiastic and patient teacher who loves his subject and wants you to love it, too. Those attributes, along with a book for a lay audience, Stars Above, Earth Below, A Guide to Astronomy in the National Parks, have pushed him to center stage of a small but impassioned movement to preserve natural night skies. When he is not lecturing at the University of Redlands, a California liberal arts college, Nordgren is a much sought-after itinerant preacher intent on bringing people revelation of the stars they have, almost everywhere, lost sight of.

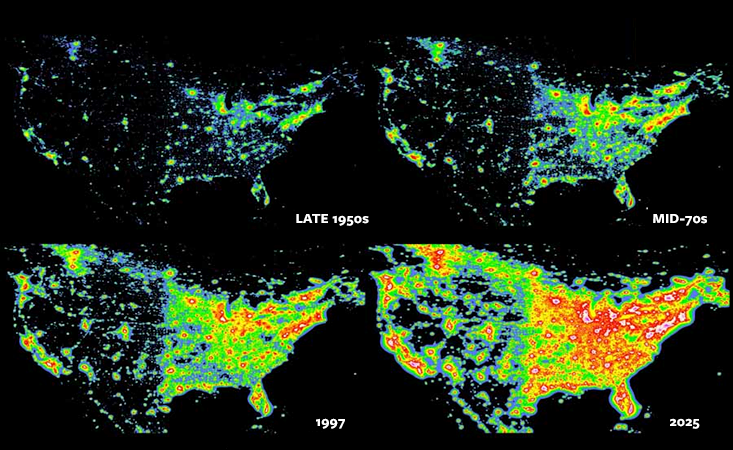

Almost the entire eastern half of the United States, the West Coast, and almost every place with an airport large enough to receive commercial jets, are too lit up to get a good view of stars. The phenomenon is illustrated by the First World Atlas of Artificial Night Sky Brightness. Based on spacecraft images of Earth in 1997, it shows a spectrum from black, representing the natural night sky, to pink, in which artificial light effectively erases any view of the stars at all. Green is where you lose visibility of the Milky Way. The map of the contiguous 48 states—and much of Europe—looks like a video-game screen showing a carpet bombing, the map a splash of green, yellow, red, and pink.

For roughly the past two decades, at least two-thirds of the U.S. population have not been able to see the Milky Way at all, and it will get worse before it gets better. The dawn of light-emitting diode (LED) lighting is expected to significantly lower costs and spur consumption. In addition, LED lighting produces light with a bluer cast, which is more effectively scattered by the atmosphere. “This has the potential to be the nail in the coffin for seeing stars in most communities,” Nordgren tells me.

Nordgren wears his hair in the style of a naval officer, cropped on the sides, and I sense that he probably looks much like the boy he once was, who had his sights on becoming an astronaut. Poor vision forced him to settle on becoming on a mere astronomer. He wrote his doctoral thesis at Cornell on dark matter in spiral galaxies, graduating in 1997. Carl Sagan, whose popular TV series Cosmos had inspired Nordgren to begin with, was there at the time, and Nordgren still regrets that whenever he was in the presence of his idol he would lose his capacity for speech. He couldn’t even find the courage to introduce himself, and when finally he did, Sagan had said, “I know who you are.”

The light pollution issue first came up in 1992 when Nordgren went to Cal Tech’s Palomar Observatory near San Diego. At the time it had the world’s largest telescope. Already, though, the night glow from the surrounding area was forcing astronomers to go elsewhere.

“In 2005, I went back to Palomar to do some work on Adaptive Optics, looking at storm clouds moving atop Uranus and Neptune, and it was really a shock,” Nordgren recalled. Giant housing, casinos, resorts. In ’92, you were like, ‘Look how bad this is!’ Then in ’05 we were just an island in a sea of lights.”

Light pollution was threatening to pull down the curtain on future research for astronomers, Nordgren said, making existing observatories useless and efforts to build new ones in the U.S. more difficult as they had to be built in places that put astronomers in conflict with environmentalists and Native Americans.

The light pollution problem grew significantly during a period that was, courtesy of the Hubble Space Telescope, a golden age in astronomy. Hubble went into orbit in 1990 and sent back images of space, unencumbered by backlighting, that would have made Galileo’s head spin. But Hubble, despite its marvels, somewhat confused the issue, leading people to assume that astronomy would proceed apace even if astronomers were being shown to obstructed-view seats. The trouble is that Hubble isn’t sustainable. Its costs are, as it were, astronomical. It requires space shuttle missions to maintain, and there are no more of those, so Hubble will be gone in a few years. The next project to replace it is over budget and far behind schedule. The long-term solution will rely on terrestrial observatories.

Finding places to put these, though, isn’t easy. As astronomers lose the functionality of existing observatories to light pollution, and move to places like Mount Graham in Arizona and Mauna Kea, the location of the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, they’ve been protested, sued, and made to feel like wanton intruders, wreckers of the environment, and defilers of sacred spaces. Really ambitious observatory projects, therefore, look overseas. When the Square Kilometer Array Telescope came up for bidding, a process like hosting the Olympics, the U.S. wasn’t in the race. Foreign observatories bring with them concerns about long-term political stability.

The question of light pollution gripped Nordgren. Like Sagan, he decided that educating the public was key. When he got his first sabbatical in 2007-2008, he decided he’d spend the time normally reserved for lab work and writing to travel to national parks to give talks. He knew from experience how visitors to the national parks wanted to reconnect to the stars above. But almost all national parks programs were about things on the land. He wanted to remind visitors that the parks, as the last preserves of natural night, were also about the skies. He devoted three weeks in each of a dozen places, among them the Rocky Mountain National Park, the Grand Tetons, Glacier, Acadia, and Great Basin.

“I was reluctant to tell other astronomers what I wanted to do,” he said. “There’s a view that astronomers should be in observatories. I remember one guy at Cornell saying, ‘Tyler, if you do education, you’re wasting your Ph.D.’ ” This was something Sagan had run into, people who assumed he wasn’t a serious scientist because he was on television. “But Carl was a good scientist,” Nordgren said. And when Nordgren did share his plans he got a warm reception. “Some people said, ‘I wish I’d thought of that!’ ” The parks rangers themselves were mostly very receptive, with some exceptions.

“There were some who had no idea what to make of what I was doing,” he said. “I remember folks at the Great Smoky Mountains, when I said I wanted to work with astronomy and night skies, the ranger said, ‘We call it ‘The Great Smokies.’ We don’t do a lot of astronomy here.’ He was baffled. And then I’d run into people in management for whom it was a 9-to-5 job. When it got dark they went home, so they never saw firsthand the night sky programs, and this was 2007-2008, when budgets were very tight.”

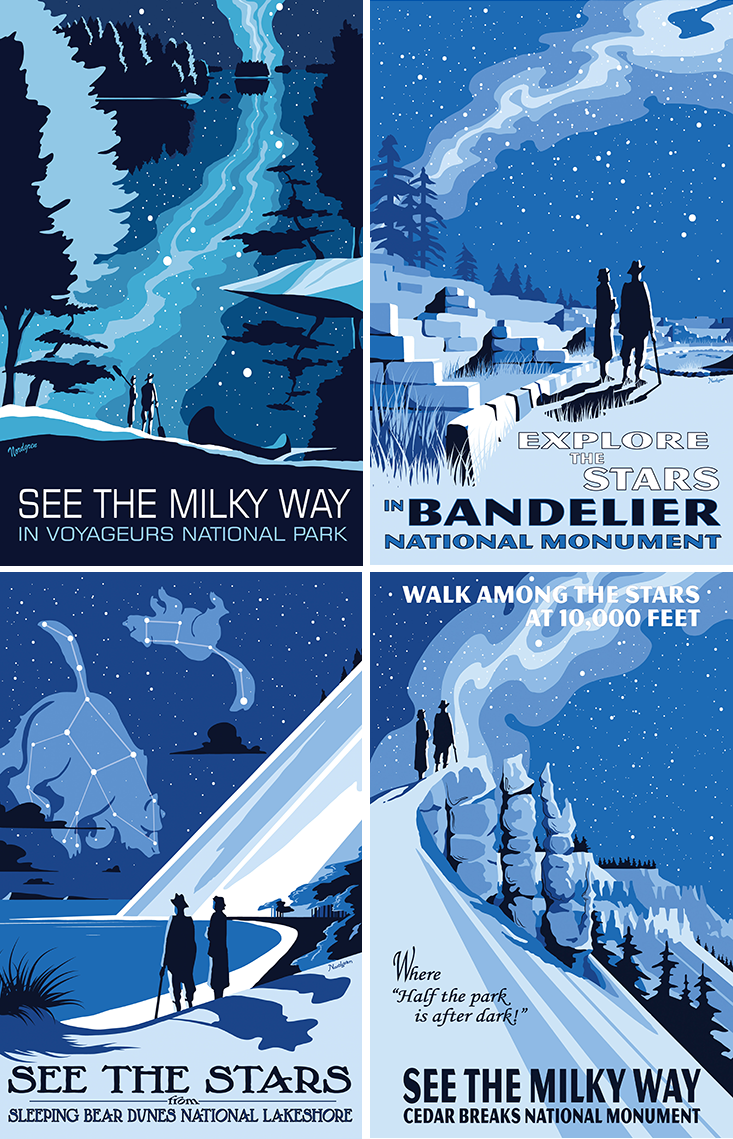

In addition to his night skies curriculum, Nordgren created an arts program called See the Milky Way. It went on for five years or so, with poster designs for 30 parks, monuments, and dark skies preserves.

The national parks odyssey also resulted in Stars Above, Earth Below, his guide which, though it sold out of a relatively modest 3,000-copy first print run and sells now through print-on-demand, found an enduring and loyal audience among rangers.

One of them was Kelly Carroll, a National Parks ranger at Great Basin. He invited Nordgren to keynote the annual astronomy festival he organized and was immediately won over.

“Every once in a while a scientist comes along who knows how to speak about science to the general public,” Carroll told me. “Tyler has a way of speaking about light pollution and the aesthetics of the issue. He helps make the connection of what it means to us to lose the night skies as human beings.”

Carroll, who was a geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey prior to joining the National Parks Service, told me that the need for someone like Nordgren is great. People are barely aware that “we’ve had an incredible part of our humanity taken away from us, but it’s been so gradual they don’t feel the loss,” he said.

Rangers tell Nordgren that the night programs get more attendance than all other programs put together. One great success story is Great Basin National Park which, in 2009, put on three night skies programs that drew 300 people. The following year they did 20 that were well-attended, so they instituted it as a primary offering. Since then overnight attendance has increased to about 9,000 a year. And while traditional daytime programs average about 25 to 30 people, the astronomy programs, which are mainly interpretive programs about night skies, typically pull in 150 to 175.

“The first time people come out for dark skies, and we get Bortle Class 1 and 2 here, it affects them deeply,” Carroll said. “They’re blown away. The connection with the stars is inside all of us, but it has been sequestered away.”

Christian Luginbuhl, an astronomer who worked with Nordgren at the Naval Observatory Flagstaff Station, explains to me that Tyler helps participants understand the cultural value of the nighttime sky. “It’s also one thing all of humanity has in common,” he tells me. “It’s the same sky in the Sahara as it is over Philadelphia. It’s also the same sky as Native Americans gazed up at 10,000 years ago. People think of light pollution as an astronomer’s concern, but Tyler helps establish this broad value, that it matters to everyone.”

I trained my eyes straight upwards, to the zenith, and settled in as Nordgren used a laser pointer to explain what we could see in the night sky: giant clouds of interstellar dust and plumes of vaporized debris, some the size of the Earth. He talked about the surface of Titan, a moon of Saturn with Earth-like features, where under a smoggy orange layer it all looks like Minnesota’s Land of 10,000 Lakes, with fractal shores and frozen methane raining out of the sky.

“We’re 25,000 light years from the center of the galaxy,” Nordgren said. “We’re way on the fringe of our own galaxy.”

“What is 25,000 light years in the other direction?” I asked.

“Then you’d be in an intergalactic area.”

“What would that be like if you were moving through it?”

“Nothing. It would be nothing.”

“But what’s nothing?” I said. “There can’t be nothing.”

He considered the matter. “No one knows,” he said. “I guess it would be like being in an inky blackness. I don’t know if you would have a perception of moving. You’d see like six stars. You know what it would be like? It would be like being in Los Angeles.”

He meant a night sky in Los Angeles.

We spend some time taking photographs, fiddling with camera settings, a lesson in shooting in the dark to augment my brief alfresco astronomy class. “Over the last decade there has been a revolution in photography,” Nordgren tells me. “Everyone has a camera now. In the 1950s, Ansel Adams went to photograph the national parks. Some feel that started the modern environmental movement. We’re there again. People are so stunned when they see the night sky photos they think they’re fake. Maybe this will be the impetus of a night sky environmental movement.”

After a cold but pleasant night by Mount Whitney, the view near dawn was splendid, the pale blue night above brightening to a spray of colors in the horizon. It wasn’t, though, the sunrise I took it to be. It was Zodiacal light, or false dawn. The beauty of a life in astronomy, at least as it’s described by Nordgren, is that every moment, it seems, is a phenomenon described in a way that’s both precise and lovely in its description.

“What you’re seeing,” Nordgren explained, “is that in the plane of our solar system, in the disk the planets orbit the sun in, there are grains of dust that float in there, in the same plane. Those grains of dust reflect and scatter sunlight. It’s exactly like the sunbeam you’d see in your house.”

Morning glory.

“The stars are still out there,” Nordgren told me. “They’re just waiting for us to pay attention again.”

This article was originally published in Nautilus Magazine on March 13, 2014.