Parallel universes have been science-fiction writers’ favorite trope ever since there was such a thing as science fiction. As far back as 1666, Duchess Margaret Cavendish wrote a book called The Blazing World in which the heroine passes through a portal at the North Pole into another universe, where the stars look different and animals can talk. In the 1930s C.S. Lewis introduced a new generation to the concept of parallel universes. “I am in your world,” said Aslan. “But there I have another name. You must learn to know me by that name. This was the very reason why you were brought to Narnia.”

Lawrence Krauss, a cosmologist at Arizona State University, thanks fiction writers for early encouragement. He watched the Twilight Zone as a boy. “There’s an episode called ‘Little Girl Lost,’” he recalls. “This girl’s parents can hear her calling them, but they can’t see her.” Her parents happen to live next door to a physicist, whom they seek out to help them find their daughter. It turns out she had fallen through a portal in her bedroom wall into another dimension. “I remember thinking, ‘Boy, one day I want to grow up and be a physicist so I can help people,’” Krauss says.

Today we know there really could be alternative realities. In some, there would be another you living another kind of life; in other theories, another dimension could exist in the same room as you. So, writers got that much right. But in a way they have been curiously unimaginative. Their multiverses aren’t nearly as extreme as the ones physicists conceive of.

The Twilight Zone episode represents one of the multiple varieties of scientific multiverse: parallel worlds separated within a spatial dimension that we are unable to move in. Another comes from the cosmological theory of inflation: universes that budded off from our own in cosmic prehistory. But both of these have a common feature. Different worlds might have different laws of physics. In some of them, you might throw an apple and it would fall up—assuming there were even such a thing as an apple. Have you seen that in any movie? Even the “Upside-Down,” the parallel world in the Netflix series Stranger Things, is just an ordinary landscape in need of a good sweeping.

Moreover, fiction keeps running afoul of the annoying rule of physics that forbids us from moving between our world and another. If those other worlds could be so easily accessed, we’d have seen them by now and there’d be no controversy over their existence. And if you could miraculously exit our world, you’d almost surely die in the process. “There goes all the fun from pop culture!” says Krauss. He elaborates: “The reason those multiverses are invisible and are not ruled out by observation is that the particles and forces that govern our life are constrained to exist in our three-dimensional universe.”

The type of multiverse that dominates comic books, television, and films is the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. In this breed of multiverse, the laws of physics do not vary, but new worlds are created every time a particle or other quantum system is presented with multiple options.

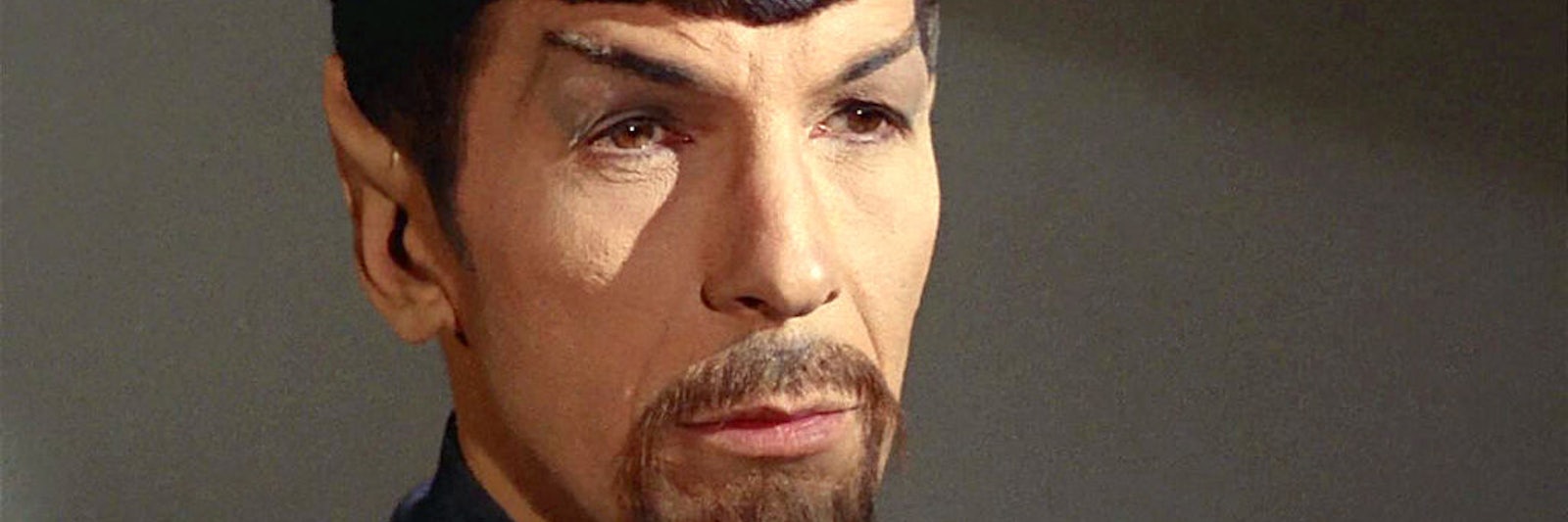

In the Star Trek episode “Mirror, Mirror” from 1967, Captain Kirk and his crew looked around their ship: “Everything’s all messed up, changed around, out of place, it’s our Enterprise, but it isn’t. Not our universe, not our ship, it’s something… parallel.” In the recent Marvel blockbuster Dr. Strange, we see Benedict Cumberbatch learn to travel between worlds. He can open portals in spacetime with mental concentration and a swirly motion of his hands.

The most recent science-fiction show produced by Netflix, The OA, follows the same multiverse path as Dr. Strange. But this time the other-dimensional universe is a kind of afterlife that does not require you to die in order to have access. When performed with a certain level of feeling, the “Five Movements”—a kind of dance, sound, yoga combo—is supposed to open a portal to a parallel world.

Unfortunately, the quantum many worlds are no more accessible to us than extra spatial dimensions or cosmological bubble universes. “The difficult thing about many-worlds,” says Sean Carroll, a theoretical physicist at Caltech, “is that the worlds aren’t located anywhere. You have a temptation to say, ‘Well, where are they? These other worlds?’ They sort of exist all at the same time, but they’re not physically located anywhere in space. They are different versions of space themselves.”

And even if they were accessible, it would take more than mere brainpower to open them. For this reason, Krauss isn’t a fan of the artistic license taken in Dr. Strange: “What really offends me the most is this New Age notion that somehow thinking about the universe determines what it is. It comes from this really perverted misunderstanding of quantum mechanics. Somehow it suggests that when you observe the universe, you change the entire universe. You can’t make the universe the way you want it to be by thinking about it.”

The multiverse movie that scientists usually rate the highest is Sliding Doors, wherein the simple act of Gwyneth Paltrow’s character missing her train creates a new branch of reality. We see the world play out as if she had or hadn’t missed her train. “That’s a pretty faithful story in terms of there is a crucial event that happened and things go two different ways,” Carroll says. “They don’t really interfere with each other in any way, but you follow the two parallel tracks.”

But Carroll doesn’t worry that most TV shows and films aren’t super-accurate. “I actually really like the idea that people get inspired by seeing these things in movies,” he says. “It’s not supposed to be scientifically accurate. The spirit of science is there.”

Lead image: Alt-Spock from Star Trek episode “Mirror, Mirror.” Credit: CBS Photo Archive / Contributor