This is the story about a singular fish. Or a hundred billion of them. Each year, one hundred billion individual fish, give or take a few billion, are intensively farmed. Hundreds of millions are kept in private homes and studied in scientific laboratories. And trillions in the wild face relentless hunting and the Sixth Mass Extinction. Fish are some of the most used and the most threatened animals on the planet—and yet, paradoxically, we may understand and appreciate them the least.

You often hear fish referred to as primitive or “lower” animals, but a new wave of scientific research reveals truly remarkable lives playing out underwater and, until recently, beneath our notice. Fish use tools, have personalities, participate in site-specific cultures, engage in parental behavior, form friendships, and can establish interspecies relationships with other aquatic animals and, it seems, with us. Stories from around the world tell of long-term relationships between particular humans and particular fish, including, for example, a viral video about a 25-year friendship between a Japanese man and a sheepshead wrasse.

Even the word itself, “fish”, lumps together a fantastic array of wildly different species, at least as many and as diverse as all terrestrial vertebrates combined. Giraffes, gibbons, geese, and geckos have their diversity matched in herring, halibut, hagfish, and hammerheads. Moreover, the vast majority of modern fish species evolved hundreds of millions of years after humans shared a common ancestor with them—which means that modern fish are not primitive forerunners to our lineage any more than humans are primitive forerunners to theirs.

And yet, fish are consistently treated as though they deserve less moral consideration than their air-breathing counterparts. In the U.S., for example, many jurisdictions do not technically consider fish to be animals, which means they cannot be protected by animal cruelty laws. On the global scale, aquaculture is a multinational corporate endeavor that attracts billions of dollars of investment and is now “experimenting” with the cultivation of hundreds of species, many of whom possess traits that would never be considered suitable for farming in terrestrial animal agriculture: carnivorous species, solitary species, species with lifespans of a century or more, and migratory species who travel thousands of miles each year.

But it is science itself that may provide the most unsettling example of our folly when it comes to fish. Scientific information about the mental similarities between fish and humans has not only resulted in an awakening of our ethical duties towards them. It has also fueled a rise in their use as models of human pathology and disease. In tandem with discovering the cognitive sophistication of fish and to some degree because of these discoveries, fish are now promoted as suitable organisms for studying depression, anxiety, stress, psychosis, despair, addiction, PTSD, and pain—studies that require their lives be made deliberately miserable.

What might fish want us to learn, not just about them, but also from them?

The yawning gap between who fish are and how humans feel entitled to treat them may, nonetheless, contain some glimmers of hope. First, the injustices that modern fish face are relatively recent developments, which means they may not be fully entrenched, yet. Second, our uniquely breezy exploitation of their lives is surely founded, in part, on a lack of familiarity. Collectively, human beings spend almost no time around fish, at least not freely living, breathing, choosing, learning, and purposeful fish. Making matters worse, fish have radically different body plans and modes of expression than humans. The net result is that fish are deeply foreign and strange to us, and the typical human response to difference is, unfortunately, debasement. But not always. Difference can also be a source of curiosity and wonder.

Fish are fleet and weightless, living in a medium (water) of which they are made, whereas we are ponderous and weighty, living in a medium (air) of which we are not made. Fish sense water flow with a specialized structure called the lateral line, taste and smell with their entire body, and can detect electromagnetic fields. Could more information about what it is like to be a fish expand our moral imagination and lead to real-world actions to shield them from further harm?

Recent history suggests a cautious “yes.” Though there is a long, long way to go, as knowledge about fish lives has improved, so too has interest in their wellbeing. Most major animal advocacy groups now campaign for fish alongside other animals. Funding bodies increasingly award grants for fish welfare research and are investing in the development of international standards of care for captive fish. Meanwhile, scholars and practitioners are forging new legal ground to support efforts to protect fish from future exploitation.

New information about fish has an important role to play in supporting these ongoing efforts. Crucially, however, knowledge about how fish are negatively affected by human activity is not enough. Making just decisions also requires that we know about who fish are. What are their interests, experiences, preferences, capabilities, and relationships? How do these features vary between species and between individuals? What might fish want us to learn, not just about them, but also from them? If approached with a spirit of humility, respect, and openness, the answers to these questions are sure to be as varied and fantastical as fish themselves.

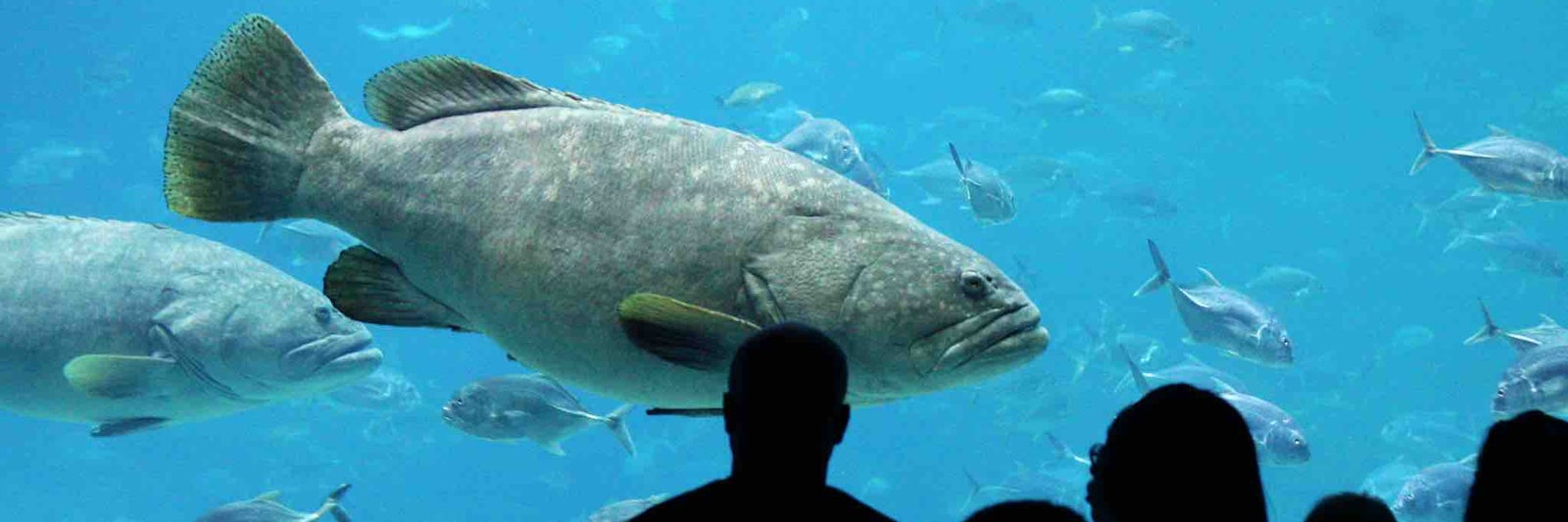

Lead image: Watching fish at the Georgia Aquarium. Credit: Madison