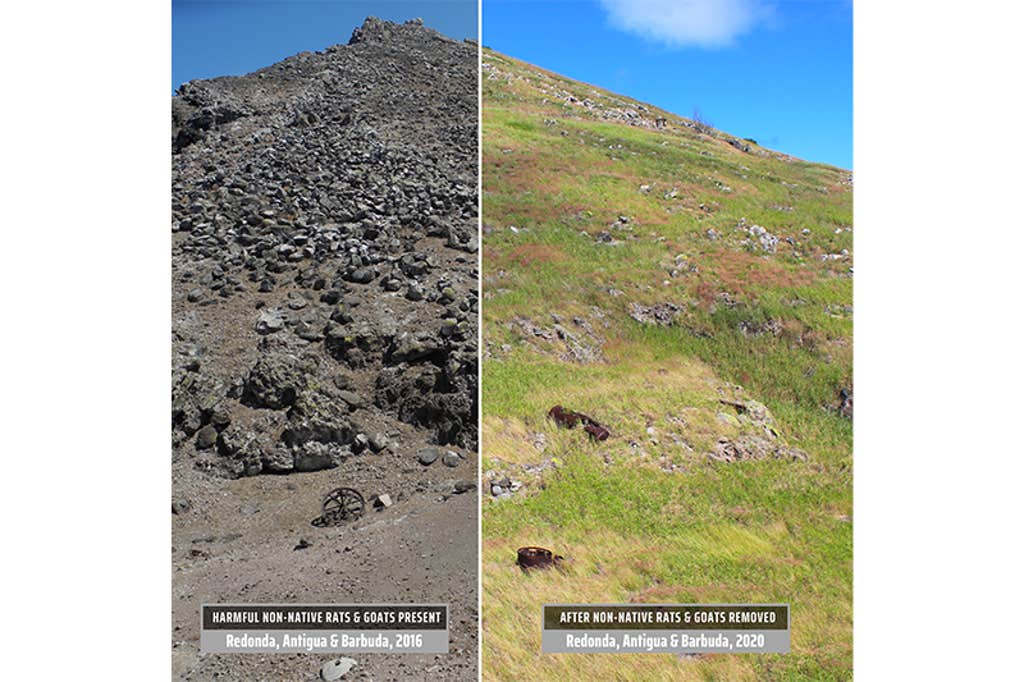

Local Caribbean lore had it that the island was inhabited by monsters—chimeras that were half human, half goat. Until recently, the reality had echoes of this dark vision. The tiny island of Redonda—just a mile long and situated halfway between Nevis and Montserrat—was overrun by 50 feral goats and 6,000 giant rats that feasted on nesting seabirds like the rare brown booby.

When the birds were away on migration, the rats turned to eating all plants and animals that remained, including each other. Once lush in vegetation and home to endemic geckos, lizards, and a thriving bird community, over time, the rats—which were almost certainly accidentally released by European voyaging ships in centuries past—turned Redonda into barren rock, with wildlife and vegetation on the verge of collapse.

Aggressive total eradication of the rats saved native species from the brink of extinction.

In 2012, the Environmental Awareness Group (EAG), a non-profit headquartered in Antigua and Barbuda focused on the sustainable use and management of natural resources in the Caribbean, started a 10 year long restoration project that saw Redonda Island revert from rats to riches. Aggressive total eradication of the rats saved native species from the brink of extinction.

The success of the mission was in part due to the work of Shanna Challenger, an Antigua local who joined EAG in 2016. Then 21 years old and freshly graduated with a bachelor’s degree in ecology and conservation from the University of the West Indies, Challenger oversaw the sweeping overhaul of Redonda in her role as the island’s Restoration Program Coordinator. The fieldwork shaped her relationship with nature, and she has since gone on to spearhead other local Caribbean conservation projects, as well as to raise the profile of endemic species in Antigua and Barbuda.

Nautilus recently spoke with Challenger over Zoom about her experience in Redonda and her vision for the future ecology of Antigua and Barbuda.

Tell us about how the rats were removed from Redonda island.

Before I tell you about the rats, I must tell you about the feral goats. I don’t know how it is where you are from, but in Antigua, people are very goat-sensitive. It’s a delicacy here; we have something called goat water—it’s kind of like a soup or a stew with chunks of goat in it. And so, the government of Antigua and Barbuda, who own Redonda island, said they were not going to support this project if y’all kill the goats. So, before we could do anything else, we had to relocate the goats. We had to bring the goats to Antigua.

Wow, okay, so how do you move goats off an uninhabited island?

By helicopter. But first we had to catch them. Redonda was very inhospitable back then. There was no fresh water, no shade during the day. We decided to build a corral, an oasis with water and shade to lure the goats in. But the goats were suspicious, they completely ignored the corral for months. So we put out traps, we put out snares. But the goats would just hop over them. We even got a net launcher. Then finally, six months later, we were able to catch one goat.

Ha. Clever goats!

Yes. And only after months of visiting Redonda were we able to see better what the goats were doing, and then we had the great idea—let us try and capture the kids! We noticed the older goats followed the kids. We thought, if we capture the kids and put them in the corral then the moms will come. And if you have moms and kids, you know who’s gonna come next? The dads! And that is how we ended up getting them into the corral from where we could move them by helicopter to Antigua.

A lot of people think that we moved them Mission Impossible-style, swinging underneath the helicopter. But it’s about a 20 minute ride, so we just held on to them. We made hoods to go over their eyes so they stayed calm and didn’t feel too stressed out about the situation. We used pool noodles to wrap their enormous horns.

So pool noodles on their horns, a hood over their eyes?

They did end up looking a little ridiculous.

Quite the helicopter ride.

Yes, we were able to bring over 50 goats from Redonda, the large ones one at a time. I will say that even while we were there on the island some were already dying. When they came to Antigua, they didn’t even know what water was really, so it was hard to get them to drink. It was hard to get them to eat, because they had gone without for so long. Some died of disease. But for the most part, we were able to save those goats. We also did genetic testing, and they have Spanish origins, which was very interesting.

On a personal note, I no longer eat goat water as you can imagine. I don’t eat goats at all after I got so close with them.

I imagine eradicating the rats was a different story altogether?

Rat eradication must be done during the driest parts of the year. That’s when the rats are super hungry, they’re at their most vulnerable, willing to do anything to get food. We covered the island in rat poison. We had a team of about 10 people do it—abseilers to access the cliffs, and ground teams. I was a part of the ground team, of course, because I wasn’t going on the cliffs.

On the ground team, we divided the island up and we placed bait every 100 feet. Within two weeks the population immediately went down.

Redonda was very inhospitable back then. There was no fresh water, no shade during the day.

Did the poison affect any of the other species on the island?

The goats were mightier than thou—they weren’t interested in the bait at all. The lizards are very curious, so they were trying to scratch at it, but it’s completely harmless to them. It’s only lethal to mammals—the antidote is vitamin K, just as a fun fact. We started the eradication in December 2016 and the last sign of a rat that we ever saw was on the 20th or so of March 2017. And to this day, knocking on wood, we still have not seen any rat signs since then.

What did you do with the rat bodies?

We collected most of them, and some are still preserved in Antigua for research. We didn’t want any going into the sea because the coral reefs around Redonda, they’re pretty important.

What does Redonda look like today?

Since the rat eradication, the island has completely rebounded. We’ve seen the lizard populations skyrocket. We have a six-fold increase in some of the species of endemic lizards. We are having plants that we haven’t seen in decades. We even had a hummingbird, and we are looking at re-introducing a burrowing owl. But we’ve not brought over any vegetation or anything, we just allowed nature to recover naturally.

Even in the marine space, we are discovering new coral colonies popping up, more foraging turtles, more parrotfish, etc.

Why would the marine areas recover, if most of the restoration work was done on land? What is the connection?

Studies have shown that when you do an invasive animal eradication on terrestrial space, there’s also a link to the surrounding marine area. When there was no vegetation on Redonda, there were a lot of rocks falling and sediment washing straight into the ocean. Big boulders just dropping into the sea and crushing the coral reefs. Since we have removed the rats and goats, the trees and roots hold the soil together, so there’s a lot less runoff and sedimentation going into the water.

There’s also an increase in the number of seabirds, which are pooping more. The guano washes into the sea and the nutrients are helping the coral recover. The ecosystem is sponge-dominated, so it’s very important for the Hawksbill turtles. And it’s a protected area, so we have restricted the amount of people who can access the near shore of the island. Reducing that human pressure, and the boat anchor damage as well, has also helped the reefs.

How did it feel the first time you saw the island changing?

I’m not gonna lie, on the helicopter coming in I started to cry because I couldn’t believe it! I thought not only has she recovered, but she was continuing to recover, and it was like this conservation, it works!

When I was camping during the rat eradication at one point there was dirt in my toothpaste, dirt in my soap, dirt in my tent, I felt like dirt the entire time. And to go from that … never in my wildest dreams would I have thought that she would have recovered so much and so quickly. Now, every tree I see, I have to take a selfie with it!

I’m at peace when I’m on Redonda. When I wake up and see all the animals in their own niche, my heart sings. It is so inspirational and so inspiring to see that it’s not just on paper that conservation works, it’s in real life. And it is local, led by Caribbean people.

Has the project changed how conservation is viewed locally?

In the world of eco-anxiety and eco-grief, people question if the environment is even worth saving. But just because all of the bad things are happening doesn’t mean that you have to give up on doing the one little good thing that you can do. We are always encouraging people to get rid of invasive species where they can, to get more people involved in the conservation field because it works, and it can happen a lot quicker than you can imagine.

Redonda’s restoration is now taught at the university where I studied. I’m so grateful to do the work that I get to do, and to show people this. We have people coming from other Caribbean islands to learn from us.

But I warn, this kind of work, it’s not glamorous. There’s nothing really glamorous about dissecting rats.

What is the ecological project that gets you out of bed these days?

I’m now primarily focused on the recovery of the Antiguan racer snake, which used to be endemic here. It’s completely harmless. All it can do is kind of give you like a little stinky musk—that is its defense mechanism. It was formerly the world’s rarest snake, now it’s the fourth rarest. Its numbers got up to about 1,200 in 2015. But, with conservation, it’s a continuous process and so even though we were able to have the numbers go up, pressures on its survival are increasing, especially since COVID-19. There’s been an increase in the number of human developments all over the Caribbean, habitat degradation, and climate change. It is getting extremely hot for the snakes.

I want to bring the Antiguan racers back to Antigua. We’re in the process of having conversations with the government to get a piece of land where we would be able to put up a predator-proof fence, and make sure that piece of land is completely free of invasive species. We are calling it an ark. ![]()

Lead photo by Ed Marshall