Victor Vescovo is one of just 70 human beings who have summited the peaks of the tallest mountain on every continent as well as traveled to the North and South Pole—an achievement known as the Explorer’s Grand Slam. But in 2019, the retired U.S. Navy intelligence officer leapfrogged his fellow explorers when he dove to the absolute bottom of each of the world’s oceans in a project called the Five Deeps.

In fact, Guinness World Records credits Vescovo as the person who has traveled the greatest vertical distance without leaving Earth. He’s also the first person to descend to the deepest spot in the Atlantic Ocean, called the Brownson Deep, as well as the Molloy Deep, which is the bottom of the Arctic Ocean, among numerous other firsts.

Superlatives and records are only part of it for Vescovo, though. As the cofounder of a successful private equity firm called Insight Equity Holdings, the science fiction-lover has personally financed a surge in deep sea exploration, spending millions on a submersible capable of going deeper and staying down longer than ever before. He’s discovered pristine, lunar-like landscapes at the bottom of the sea, and encountered life forms previously unknown to science, such as a new species of snailfish and stalked tunicates known as Ascideans. Using the best mapping sonar available outside of the military, he’s also mapped these regions in greater detail than ever before.

Vescovo has even begun taking others down into the ocean’s depths. On February 10 of 2020, HSH Prince Albert II of Monaco accompanied Vescovo in his submersible, the DSV Limiting Factor, on a dive to the Calypso Deep, the deepest point in the Mediterranean Sea. In June of 2020, Vescovo was joined by Dr. Kathy Sullivan, an astronaut and the first woman from the United States to walk in space, to the lowest-lying point on the planet—a plain at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean’s Mariana Trench, some 35,872 feet below sea level, known as Challenger Deep.

Nautilus recently had the chance to sit down with Vescovo over Zoom to learn more about his experiences in the deep.

Let’s start with the first thing any sane person would ask you. What’s it like to be at the bottom of the ocean?

The first feeling was definitely relief that it actually worked, and I was still safe. And then that second emotion is just a great sense of elation and victory that we actually pulled it off, and I’m actually here. It is such a rare thing for people to do. I think I was only the fourth person to [touch down in the Challenger Deep] so there’s a great sense of pride, not just for myself, but for my whole team that was able to make it happen. And then, the third kind of emotion was almost like being a kid. I mean, here I was back in April of 2019, and I had my own submarine at the bottom of the ocean, and I had no real agenda other than to go exploring where very, very few people had ever been before or not at all.

I had my own submarine at the bottom of the ocean, and I had no real agenda other than to go exploring….

You have encountered frostbite and altitude sickness during your ascents of the world’s tallest peaks, and even survived a really serious rock slide. Have there been any of those oh-shit moments in the submersibles?

There have definitely been some of those moments. In testing, when we first took the submarine down to 5,000 meters in Great Abaco Canyon off of the Bahamas, we had a little bit of an electrical short inside the capsule. We actually saw a small puff of smoke. We were two hours from the surface, and that’s the last thing you ever want to see or feel. And we understood quickly kind of what had caused it, but it certainly caused a couple of seconds of intense emotion. And then on one of my dives at the Tonga Trench, the second deepest place on earth, I was actually at the bottom, and I got some indications that I was having a “thermal event”, as we euphemistically call it. One of the large batteries in the submarine that is outside the pressure capsule was having a serious issue. It turned out that it was having a large dump of voltage. It was basically on fire.

You can’t really have a fire at that depth and under that pressure, but it was melting. I isolated the battery. The training took over and I solved the condition, and I actually continued to dive for about another hour until my batteries drained out and then I ascended. But I’ve been a pilot since I was 19 years old and I’ve trained in aircraft of all types and helicopters. And it’s the same discipline where any number of things can go wrong, but you have so much training and you repeat the emergency procedures so many times that it just becomes automatic, and you do what you need to do to solve the issue and get back safely.

Can you talk about the difference in feeling between climbing a peak like Everest and descending to the deep ocean?

When you are climbing, especially on that last summit day, people don’t really realize it but you have tunnel vision. You can barely take care of yourself or really be fully aware of what’s around you. You’re hypoxic, you’re exhausted. You’re in goggles. Climbing Everest or any large mountain is physically punishing. It is grueling. You’re doing it for months. You’re out in very difficult conditions. You’re always cold. It’s a very different experience than going to the bottom of the ocean, which is much more of a mental and technical challenge. It’s more like going to the moon in a capsule where you’re in a dangerous situation that if anything dramatically goes wrong, it could be a very quick trip to the nether-lands. But it’s similar in that there is danger there.

I think there’s more danger in mountaineering than there is in deep ocean diving. But it’s something that you train for. And when you go down to the very bottom of the ocean and you are exploring places that no human has ever seen before, and you know that just outside that window is eight tons per square inch of pressure, in the back of your mind you’re going, “That’s pretty extreme. Is this really safe?” But you know that it is. It’s just like getting into a jumbo jet and flying at 33,000 feet. People don’t think twice about it anymore, but in the early days, that was a serious endeavor.

Can you describe what it’s like to find trash in a place that no one has ever been before?

Within about 15 minutes on my very first dive to the Challenger Deep, out of the corner of my eye I saw a sharp right angle, and nature doesn’t do that. I turned the submarine around, and I got closer and sure enough, it looked like it was plastic. It could have been fabric. I wasn’t quite sure, but it had faded lettering on it, almost a stylistic ‘S’. So there was no question that it was human contamination. Now fortunately, that was the only visible human contamination I saw on the Challenger Deep—other than, and I have to point this out, cables from remotely operated vehicles from other scientific expeditions. I’ve now seen far, far more of that at the bottom of the Challenger Deep than I have of any human consumer contamination. In fact, I’m now a joint author on an article that is basically saying parts of the Challenger Deep should be a no-go area for any kind of submersible device, because they almost certainly will get entangled due to the sheer volume of contamination.

At the Calypso Deep at the bottom of the Mediterranean Ocean, when I was with Prince Albert, he and I directly observed just a wide variety and a significant amount of human contamination from plastic bowls to ropes, to rigging, to random pieces of metal, definitely plastics and all sorts of things. It was pretty extensive, which was unfortunate.

You were just saying ROV cables from scientific exploration are now among the pollution at the bottom. Do you ever worry that what you’re doing may be changing these places, and also opening them up to future exploration, deep sea mining, anything along those lines?

It’s certainly a balance. One can look at, for example, Mount Everest, where so many people, including myself, have ascended. On certain days, it’s just packed with climbers trying to get to the summit. But the issue here with respect to the deep oceans is that Hadal exploration—that is, exploration below 6,000 meters—is so incredibly rare and the oceans are so massively large, I think that we are well on one side of that equation, that the benefits of exploration far, far outweigh the damage that we could potentially have in it. These are completely new areas to explore with respect to geology and marine biology. There is so much to discover. Especially in a manned submersible that does not have an expendable tether. All we have are steel weights that will rust out over time. You can’t even see them once you leave the area because they blend in or are submerged by the bottom. I think we have a minimal impact. Yet the scientific data that we come back with is very valuable.

Do you ever think about the privilege inherent in what you do? You’re seeing things scientists have spent their whole lives studying, but never seen. How do you think the role of the entrepreneur and the adventurer can complement that of the scientist?

Absolutely. I think about that quite a great deal. And I feel extraordinarily fortunate that I live in a society that allowed me to work very hard for many decades to create the wealth that made the expenditure of monies possible to create this submersible and, frankly, this whole diving system—including the sonar, the full-ocean-depth landers—and then go explore.

If one looks back in history to the Golden Age of Exploration, where private entrepreneurs sponsored expeditions to the Arctic and the Antarctic, without them we wouldn’t have had a lot of the exploration that we did. Going even further back to the Middle Ages, it wasn’t even the nobles or other people that were always sponsoring the science. It was wealthy merchants that had issues that they wanted to solve or traders that wanted to have a good economic outcome and set people off to explore new routes to Asia or other places. So there is a role for wealth creation driving scientific advancement, and I just feel privileged to be part of that very long chain.

In February of 2020, you invited H.S.H. Prince Albert II of Monaco to join you on a descent to the Calypso Deep, or the deepest part of the Mediterranean Sea. Prince Albert II is known as one of the world’s most environmentally-committed Heads of State and later said the experience inspired a “feeling of approaching the truth about nature and about humankind.” How did that collaboration come about?

I was invited to visit Prince Albert II in Monaco when he heard about the Five Deeps expedition. His great-great-grandfather, Prince Albert I, was a significant explorer in his own right. Actually, there are parts of Svalbard in Norway that are named after him. And when we went down to the Challenger Deep, we caught biological samples of amphipods that were named by the original Prince Albert I. So I went to Monaco and presented those samples, and he was very appreciative. And then I just off-handedly remarked, “You know, we’re going to go to the bottom of the Calypso Deep. You’re welcome to come if you’d like.” I didn’t think he’d seriously consider it. But a week or two later, his staff came back to me and said, “Yes, actually the Sovereign Prince is very interested. He’d would be very much interested to do this dive.” I later discovered that he loves doing personal exploration himself. He’s been to the North Pole, the South Pole, all these other things. So it was just a pleasure to arrange that with him, and it certainly made the permitting process go a hell of a lot faster.

What’s the most surprising, or shocking, or amazing thing that you’ve seen in all these dives? Is there a single thing that really stands out?

A lot of people told me that when I got to the bottom of the Challenger Deep, it’s pretty much a moonscape—that it’s relatively lifeless. And so I wasn’t expecting that much. And yet within about five or ten minutes of being on the bottom of the ocean floor, I saw something. I thought it was just a carcass. But as I got closer to it, it was a little holothurian—a sea cucumber. But an unusual, flat type. It was just a couple of inches long, but it was absolutely alive. In fact, it was undulating and swimming away from me. I think it was scared of me. And that really struck me in a positive way, too. I went, “Wow.” I thought there was going to be much less life. And yet right there was this little creature just trying to make his way in the world. And then I saw a lot more of them. So there was a lot more life at the bottom of Challenger than I expected.

We have seen the deepest octopus ever recorded. We’ve seen the deepest jellyfish ever recorded at 9,000 meters. We’ve recorded the deepest fish ever recorded. And we’re very proud of that because it actually has expanded the envelope of what marine biologists say is the depth capability of all these organisms. These are the kinds of discoveries that we’re hoping to engender and hopefully contribute to marine science.

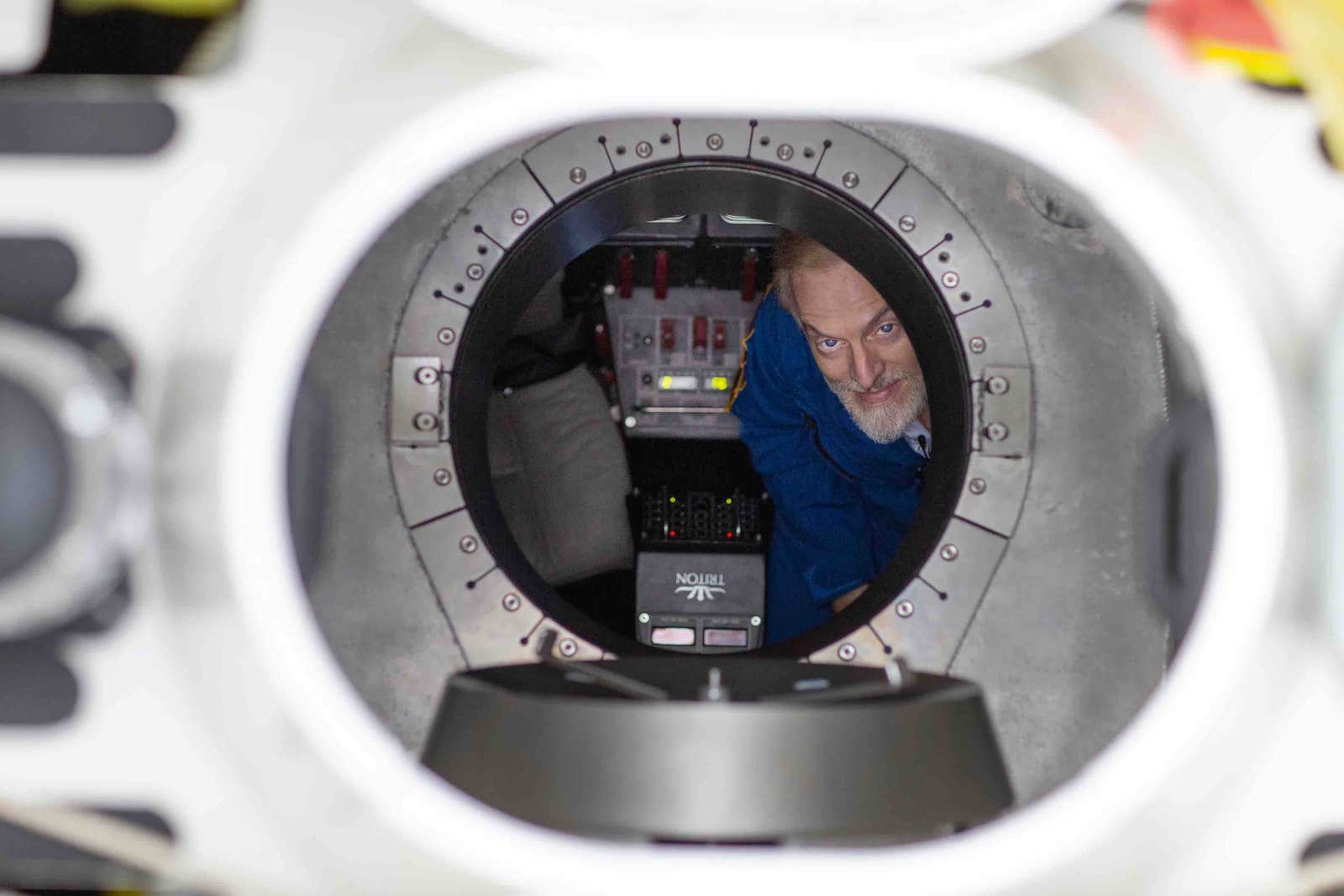

Lead image: Victor Vescovo inside the submarine that he piloted to the bottom of Calypso Deep, the deepest part of the Mediterranean Sea.