According to myth, ghostly blue lights often called will-o’-the-wisp can trick travelers wandering through cemeteries or wading through wetlands, leading them off track and toward their doom. These lights were thought to derive from the flickers of lanterns carried by otherworldly beings such as fairies and ghosts, who were intent on misleading hapless humans. Such sights have long stirred “vulgar superstition and philosophical curiosity,” wrote the Rev. John Mitchell in 1829.

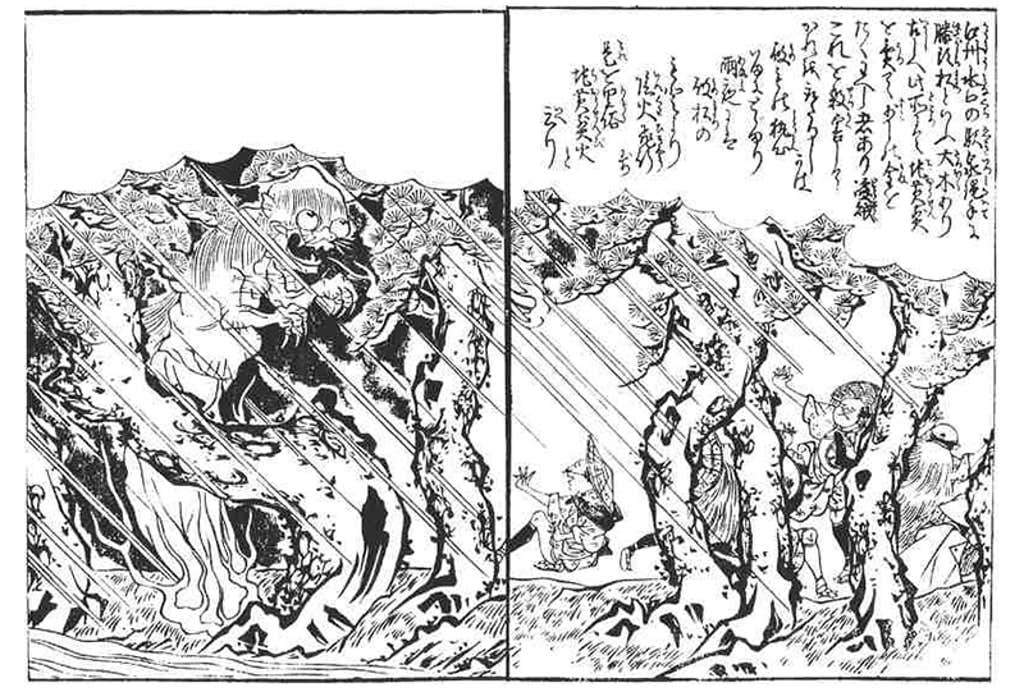

Also known as jack-o’-lanterns or hinkypunks, among other whimsical monikers, these types of apparitions have appeared in stories and artwork from around the world, from the United States and Japan to Scotland and Thailand.

It has long been suspected that these seemingly supernatural happenings were actually a natural phenomenon: “Fables … are of little value for the purposes of science,” Mitchell noted two centuries ago, suggesting that the true source was “a vapour,” possibly hydrogen sulfide, “issuing from the mud” that then ignited upon contact with the air.

More recent research has pointed toward methane as the culprit: As decaying organic matter in these wet environs releases methane, this swampy gas undergoes oxidation in the air and suddenly ignites to produce that spooky blue glow of lore. But it wasn’t clear what set off this spark out in nature, because oxidation typically requires a significant pulse of energy. “That has been the mystery for this spooky light,” wrote Richard Zare, a chemist at Stanford University, via email.

Now, Zare and his colleagues say they have illuminated the jolt behind these mystical flames: “microlightning,” according to a study published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

When bubbles of methane reach the water’s surface they burst, Zare says, creating a mix of positively and negatively charged “microbubbles.” When bubbles with opposite charges mingle, it sets off a tiny flash of lightning. This spark kick-starts the oxidation of the methane and the corresponding blue glow.

Zare and other scientists coined the term microlightning in 2024 when they observed the same phenomenon in water droplets. To see whether this could explain the will-o’-the-wisps mystery, the researchers designed a “microbubble generator” that shoots methane-air bubbles into a tank of water.

Amid “dense bubbling conditions,” the authors recorded quick flashes between bubbles that seemed consistent with microlightning. They also observed other signs of these small flashes in the tank, including slightly increased water temperature and leftovers from methane oxidation such as carbon dioxide.

This revelation goes beyond spooky bogs: Zaps of microlightning in mists of watery spray may have even triggered the chemical reactions that forged the molecules needed for the earliest lifeforms.

“When you realize the possible connection to making the building blocks of life on early Earth, it is in my opinion potentially quite profound,” Zare says. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter here.

Lead image: Hermann Hendrich / Wikimedia Commons