A few years ago, astronomers at the European Space Agency took a snapshot of the early universe. The image is oval and speckled with blue, orange, and red dots, signifying slight temperature variations where galaxies and giant voids of empty space would one day form. It captures the cosmic microwave background, ancient light created when the universe was only 370,000 years old. The physicist Brian Greene said it was as beautiful as any piece of art. But Jonathan Feldschuh, a New York-based artist, disagreed.

Feldschuh, who has a physics degree from Harvard, thought that the image didn’t really capture what was so remarkable about the discovery. He wanted many people, not just world-class physicists, to feel moved when peering at evidence of our universe’s fiery birth. So, he set out to create a new, artistic representation of the data in the hopes of astonishing more of us.

In his series called “The World Egg,” Feldschuh downloaded the European Space Agency Planck satellite’s raw data and processed it with the same software used by astronomers. He then used digital media to transform the points of light into wispy whorls of color that didn’t precisely match the temperature variations in the data, but pointed to something beyond them. “I wanted to make an image that conveyed one idea really powerfully,” he says, “The all-inspiring nature of what we’re doing and what we’re seeing.”

Images are part of a rich and sophisticated dialogue that extends back thousands of years.

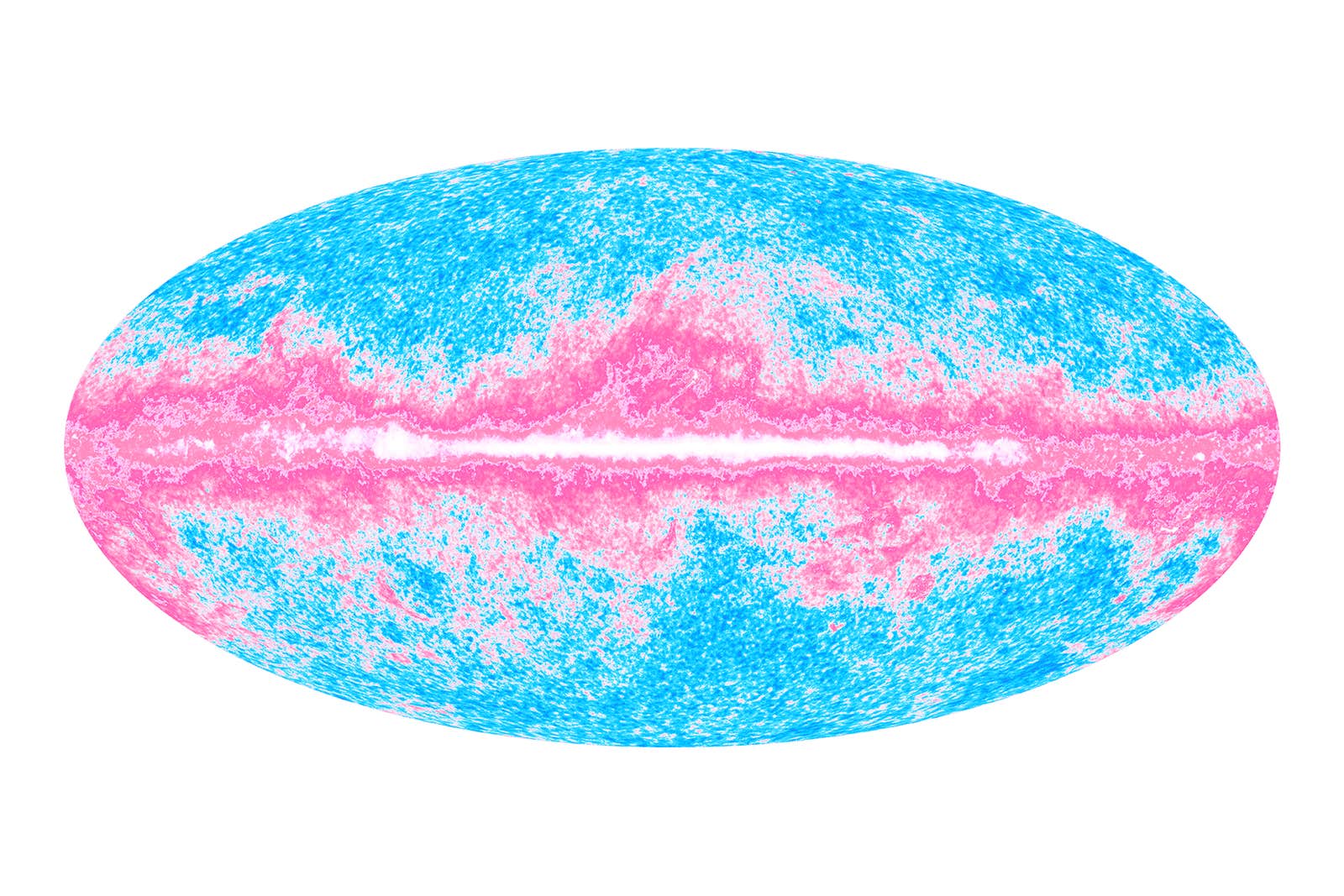

Take, for example, his piece titled “Universe Baby Picture,” in which he symbolized the early cosmos by coloring the picture the same pink and blue hues of the standard swaddling blankets in hospitals. To add visual tension, he placed in the foreground a flaming white-hot strip representing the Milky Way, which he likens to a Faberge egg on the verge of cracking open. The juxtaposition creates an awe-inspiring image of the universe’s infancy.

“Scientists often ignore the way that images convey anything other than actual information,” he says. “But as an artist, you’re very aware of the fact that images are part of a dialogue that extends thousands of years and is incredibly rich and sophisticated.”

Like Feldschuh, many creative individuals throughout history have used the language of art to transform scientific discoveries into something that resonates more deeply with culture and society. We need only think of Albrecht Durer, the German Renaissance artist who integrated medical theories into his etchings, or the 19th century painters who created grand creature-filled landscapes inspired by the work of Charles Darwin. Today, a new generation of artists is taking its cue from the recent advancements in modern scientific cosmology, and Feldschuh, Jody Rasch, and Gianluca Bianchino, are a few shining examples.

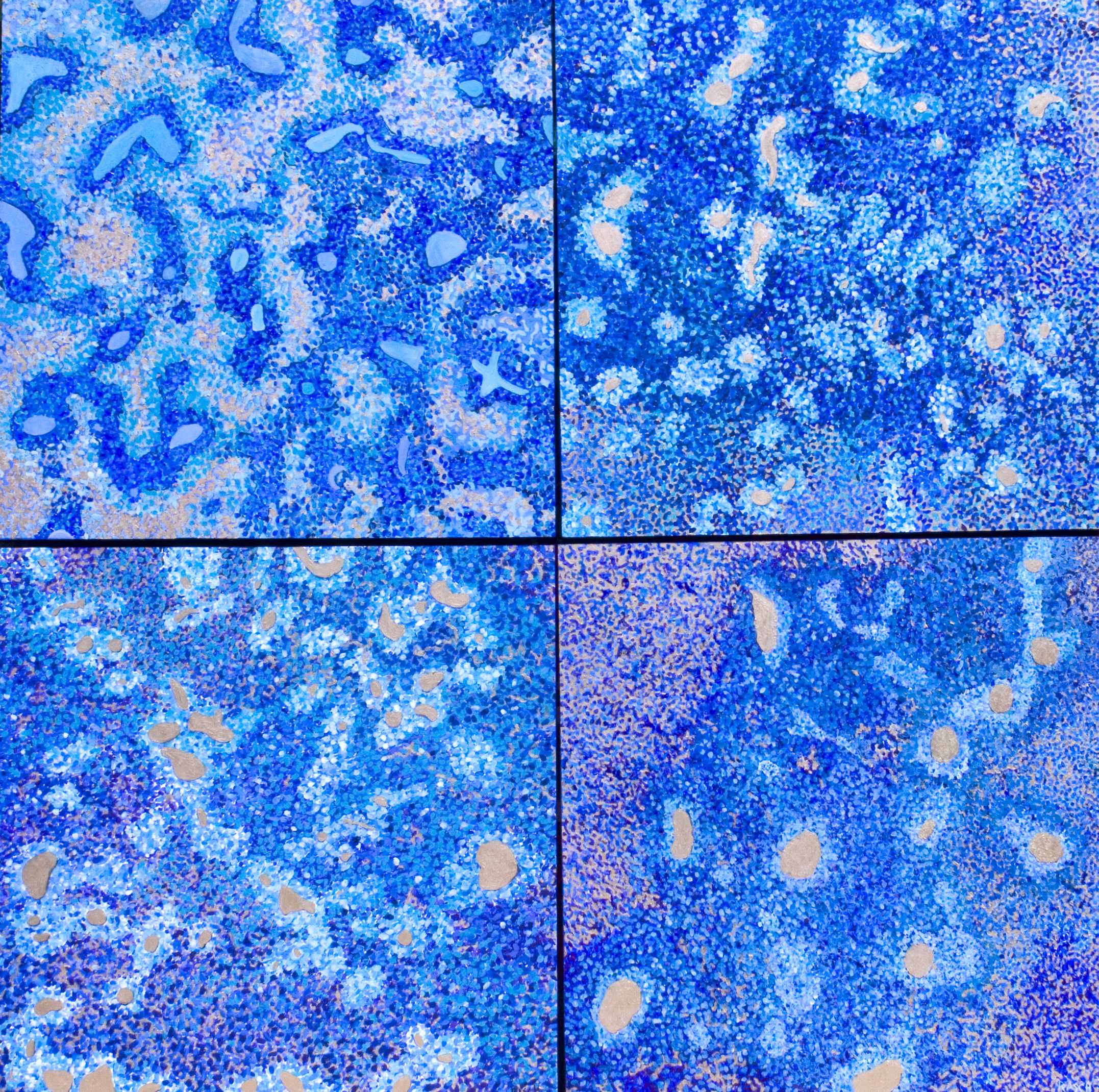

Rasch, another New York-based artist, is drawn to how scientists render the invisible visible, particularly with phenomena like black holes and dark matter. One example is his fascination with four images taken by the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope on Mauna Kea. These images are of four different regions of the sky at four different points throughout the year, and together capture roughly 10 million galaxies. They also map the elusive and still-theoretical dark matter, which is made visible in shades of blue and white. Taken as a whole, the images feel out of focus, as if you’re looking at a brilliant night sky through smudged glasses.

“A lot of what I’m trying to do is communicate the philosophy behind the science.”

Under Rasch’s artistic influence, the original images are transformed and imbued with meaning. His piece, “Four Seasons of Dark Matter,” includes four individual panels, each painted to represent one of the original four images. Although his compositions are still abstract, he didn’t want a facsimile of the original, and so chose a lighter blue palette. He also varied the sizes of the shapes, creating visual depth that is easier on the eye. He formed the shapes using pointillism, a technique in which small, distinct dots of color form an image, allowing him to play on the idea that the scientific images are themselves created by tiny particles of light. He also placed gold on selective portions of the paintings, making the invisible visibly brilliant.

But for Rasch, the gold serves an additional function. In medieval paintings, the commanding power of gold was often used to identify holy figures. Taking inspiration from these paintings, Rasch says he “wanted to capture that same feeling and concept but in a very different environment.” By adding gold to his science-based paintings, he invokes the idea of gold as a symbol of power and makes a statement about the role of science in the world today: It’s taken religion’s place. “A lot of what I’m trying to do is not to communicate the science, but the philosophy behind the science,” Rasch says.

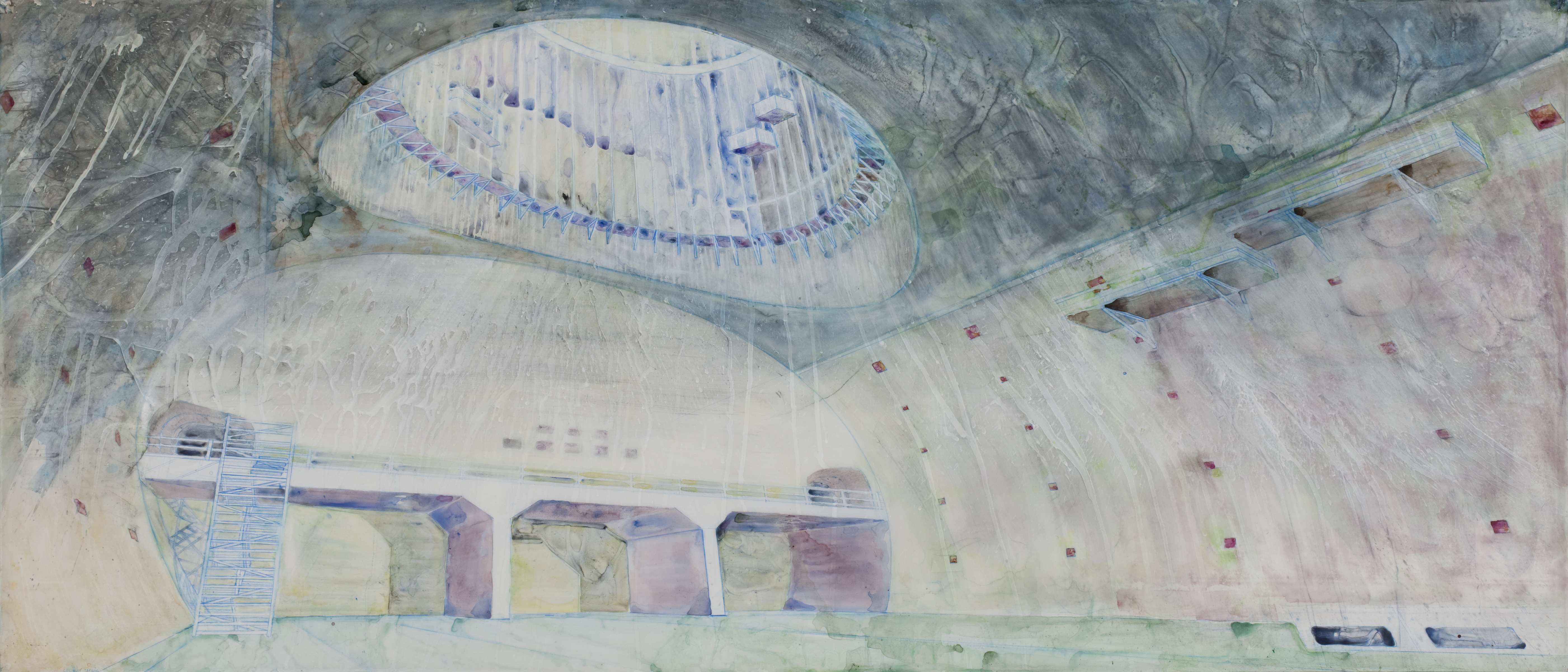

Feldschuh does just this in his stunning Large Hadron Collider series. Victor Weisskopf, a former director-general of CERN, once referred to particle accelerators as the “gothic cathedrals of the 20th century.” Feldschuh agrees. To him, the grandeur of the Large Hadron Collider, a 27-kilometer-ring beneath France and Switzerland, is similar to that of an ancient cathedral. Both were massive undertakings, requiring hundreds if not thousands of individuals to complete their construction, and both are places where we ask the deepest existential questions possible. One of his paintings shows the Large Hadron Collider’s empty halls casting the same heavenly glow that a church’s cupola might.

The pieces in the Large Hadron Collider series are painted on both sides of sheets of Mylar, a plastic-like material traditionally used for architectural drawings. On one side, Feldschuh made painstakingly precise drawings of the facility to represent the engineering prowess. On the reverse side, he made a splatter painting by dropping paint from a ladder onto the sheet. It represents the moment of impact when particles within the accelerator collide, reminding viewers of the machine’s goal to explore the unknown. Both sides of the Mylar sheets juxtapose the large with the small, a theme that can be seen within the collider itself since physicists had to build a huge particle accelerator to observe the lightest particles. In this way, Feldschuh transforms a complex scientific instrument into a statement about one of our greatest human endeavors.

Bianchino, a New Jersey artist, is inspired by string theory and orderly chaos. One of his most notable series is titled “Space Junk,” an installation that employs found objects, such as umbrellas and painted pieces of wood, lights and videos to resemble the satellites slowly falling apart high above the Earth. The many lights cast colorful shadows of the physical objects. This suggests a world that’s so materially complex that it appears to harbor more dimensions than our own, hinting at the hidden dimensions postulated by string theory. Although the sculpture looks hectic, some of the shadows move across the wall in well-defined patterns. The sculpture encourages us to think about the unorchestrated ballet of real space junk, floating just miles above our heads.

It’s this sort of wonderment that science points us to and that Bianchino believes art can instill in us. In his series called “Transportals,” spectators peer through lenses, some of which are mounted so low on a wall that a tall adult must bend down and assume the viewpoint of a child—which is precisely his goal. “Ultimately, what I’m trying to bring to viewers is a child-like curiosity about the universe,” he says, “which I think may have been lost.”

Lead Image “Universe Baby Picture,” by Jonathan Feldschuh