By the seventh month of my pregnancy, I sometimes felt a stroking motion on the inside of my abdomen, a repeated arc of movement traced by a tiny limb.

My daughter Lucy weighed 6 pounds when she was born two months later. My father’s side of the family often produces small babies. Too small to regulate her own body temperature, she needed to be held in order to sleep. She was “living on” me, the pediatrician said.

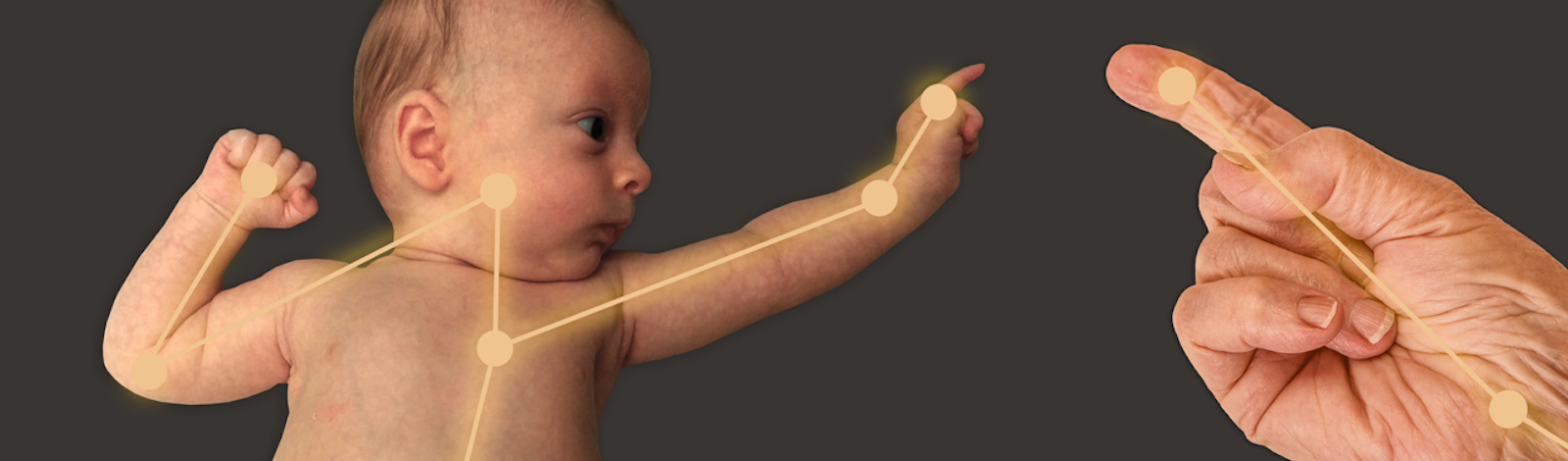

Sometimes to free up my hands I would lay her along my thighs, the dip between them holding her snug. Her wrinkled arms and legs stayed drawn in to her chest, but then one arm and leg would extend, the arm reaching out in front of her and sweeping out to the side, taking in the expanse of the room until she lay twisted like an archer. The motion already was familiar to me: the asymmetrical tonic neck reflex.

When a baby’s head is turned to one side, the asymmetrical tonic neck reflex prompts the infant into the archer’s pose. One arm extends, while the opposite arm and leg flex. This reflex begins about 18 weeks after conception and helps the baby to make her way down the birth canal. Outside the womb, the fencing (or archer’s) reflex allows the baby to discover her hands and develop hand-eye coordination.

When my parents came to New York to meet Lucy, she lay in the crook of my father’s arm, tracing her lazy arcs across the ceiling. Dad’s dementia was advancing, but he knew how to hold a baby. He’d raised six.

Lucy fell asleep on Dad, and I watched them together, remembering the smell of my father’s skin as I had drifted off to sleep against him as a child. “Slow, steady heartbeat,” said my mother. “That’s what babies like.”

I took a picture of Lucy’s hand, uncurled in sleep against Dad’s spotted skin. He had artist’s hands, tools well-used. My mother said Lucy had “starfish hands,” the tiny, translucent fingers tapered at the tips. “She’s like a dancer,” said my mother. “Our little archer.”

Primitive reflexes develop before we are born and their primary function is to nourish or protect us. Neurologists call them “primitive” in part because the infant’s brain has traditionally been seen as a primitive edition of an adult’s. Also, primitive reflexes fade as we grow up. When neurologist Marshall Hall coined the term “reflex” in the 1830s, he positioned it in direct contrast to voluntarily activity—that is, activity controlled by the frontal cortex.1 In the 1930s, the neurologist Gysbertus Rademaker reinforced this hierarchical view, describing primitive reflexes as basic units that gradually became hidden as higher brain centers became more active.2 These neurologists saw the nervous system as separate compartments that slowly connected as a child grew, uniting under a “gradual increase of cortical influence.”

The hierarchical understanding endures today. But, as the neurologist Bert Touwen wrote, primitive reflexes in infants belong in a different category than those that practitioners test in both children and adults during an annual physical. A tap on a patient’s knee or elbow with a rubber hammer elicits a simple nerve circuit response. The suckle, grasp, or fencing reflexes are more complex and variable. Moreover, they have a way of coming back.

There’s a porous boundary between reflex and reaction.

Primitive reflexes can be activated in patients with advanced dementia, coexisting with voluntary movement. Conventional wisdom holds that the work it takes the cortex to suppress them becomes too taxing in old age. Keeping the heart beating and the lungs inhaling and exhaling has to take priority. Traumatic brain damage and neurologic disease can also bring back primitive reflexes. Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and other forms of dementia involving frontal cortex lesions can impair the connection between intention and action, making room for reflexes not seen since infancy. Deep anesthesia can produce this same effect. Doctors talk of patients who, under heavy sedation, grasp someone’s finger, root for a breast to suckle, or twist into the archer’s pose.

Brocklehurst’s Textbook of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology calls the phenomenon of primitive reflexes returning in adulthood “cortical release.” To this day, cortical release is not well understood.

When Dad first went into the nursing home near his and my mother’s home in western New Hampshire, we read him the Just So Stories, a favorite from his childhood. I would bring him wildflowers I picked on the hill where my parents lived. One morning in August, I walked in with a bouquet of goldenrod. “I didn’t even know it was summer,” he said, his voice swelling with sadness. It was a rare return of speech after months of silence.

A few evenings later, I was driving up to the nursing home and noticed children playing baseball. The warm summer light colored their white uniforms pink. “Can I wheel him down in a chair to watch?” I asked his nurse.

“I wouldn’t advise that,” she said. “Too risky.”

I massaged Dad’s hands and feet like he had taught me when I was young. He retired from the graphic design business when I was 3, so my family had breakfast together in my parents’ bed every morning before school. Toast and jam. He’d use the tea cozy as a hat and pretend he was the pope. “Rub my hands before I go paint all day,” he’d say.

After school, I’d visit him in his studio behind the house. “I just can’t believe all the knowledge I’ve worked to acquire is going to die with me,” Dad would say to me. “Why won’t you let me teach you calligraphy, or how to sail, or how to build a box kite or a Japanese garden?” My awareness that he was older than other fathers, that it was already time to pass down knowledge, was too much to take on just yet.

A few weeks later, we got a call to come home again. “Only if it’s not inconvenient,” said my mother, reflexively reverting to English politeness in her pain.

His eyes were wide and his face full of wonder, trying to show my mother what he could not say and what he seemed to know she could not see.

The director of the nursing home met with me and my sister, our mother mute with sadness beside her. “His pneumonia is progressing,” she said. “I’d give this a week. Everyone’s different, but this looks like a week to me.”

We went back to Dad’s bed. “You’re doing everything just right,” my mother told him with a kiss.

He lay back and listened. After a while we were silent, and he stretched out his leg before tracing slow arcs in the air with his hand. Over and over again his arm gathered in and uncurled, taking in the scope of the room.

His eyes were wide and his face full of wonder, trying to show my mother what he could not say and what he seemed to know she could not see.

It was Dad’s fencing reflex, the same gesture Lucy had practiced before her birth to ease her passage from one world to the next.

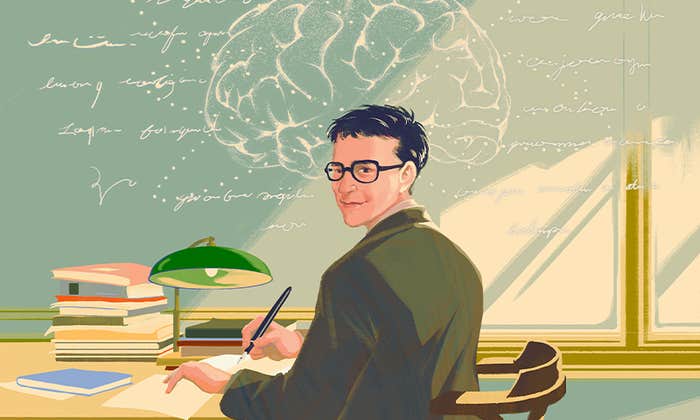

There is a video of Dad and Lucy from the year before he went into the nursing home. In it, they are seated on opposite sides of the breakfast table in New Hampshire, surrounded by my mother’s houseplants. They are drawing, though Dad hadn’t been down to his studio to paint in a few years by that point. We had brought up some sketching pens, but he ignores them for a row of Lucy’s chunky toddler crayons. Lucy, 2, uses a paint box.

They focus hard on their work, chins down, lips pursed with purpose. They both breathe through their noses. Dad’s white beard, longer than he had kept it before his illness, rests on his chest. The dog walks through, sniffing under them, but they are busy and do not immediately notice.

Lucy stabs and swirls her brush, pushing the color across the page. Dad lifts his crayon like a conductor’s baton, each finger poised and light. He places it gently on the paper, just as he had handled a paintbrush in the past, and draws a complex purple squiggle. He pauses at the end to stroke his beard and squint at the paper as he had his canvases.

He shifts a white crayon to the back of the line and uses a bright pink one to trace above the path of the original purple. Then a blue, then an orange. With each pass, the loops swell higher, the sharp corners pinch more tightly.

There’s a porous boundary between reflex and reaction. We sometimes think of our reactions to crises as reflexive, but they are behavioral, originating from the less ancient parts of our brains. Reflexes, too, can be colored by experience. The neurologist Karel Bobath wrote that he favored the word “reaction” to describe an infant’s step reflex, in order to express the “variability and potentiality of adaptation to the different demands of the environment.”3 Touwen wrote that neurologists are not always strict about the separation between the terms “reflex” and “reaction.” Reflexes, he argued, do not exist separately from the world. He preferred to view the nervous system as existing in a “dynamic state,” one that grew “because of a continuous influx of energy and information.” The rooting reflex, for example, begins with a rhythmic side-to-side motion before developing into a complex function, a gathering-in of the breast. Whether “reflex” or “reaction,” Touwen wrote, these responses must be an “age-specific display adapted to the infant’s needs.”

Watching the video later, I couldn’t help but wonder if a part of Lucy’s drawings that day had grown out of her primitive reflexes, and if Dad’s drawings weren’t informing his remerging ones.

The evening after I got back to New Hampshire, I climbed into bed with Dad and curled my body around his. It was a protective gesture, but it was also full of longing, an effort to absorb all the time that was left. We watched Audrey Hepburn and Gregory Peck in Roman Holiday, both of us dozing on and off. Dad had grown up collecting bottles to pay the 11-cent entrance fee for Saturday afternoons at the Commodore movie theater in West Philadelphia. He and his brother Brad had taken acting classes together at night for fun when they were young men. Dad loved to tell a story of Laurence Olivier immersing himself so fully into a role that he had had no recollection of how the performance had gone once he came off stage.

Later that night, I leapt out of bed and stood in the stark light of the hall between our bedrooms, clasping hands with my mother and sister in a strange, impromptu circle. My mother was mute. We took a breath.

“Dad died,” my sister told me.

“Already?”

Primitive reflexes can be used to determine brain death. The jaw is tapped with a reflex hammer. Response to pain and the cough reflex are assessed. In the cold calorics test, ice water is piped into the inner ear to check for eye movement.

Neurologists say that the loss of any meaningful consciousness is fairly sudden. Five minutes after the heart stops, neurons begin to die. There is a similarity between out-of-body experiences under deep anesthesia and in near death, but after 10 minutes at the outside, life is gone.

A reversion to primal reflexes easily explains away a deathbed hand squeeze. Another reflex associated with death is more rare. With activation of the truncal muscles, as when a braindead patient’s chin is pushed toward the chest, or a respirator is disconnected, a signal is sent to the spine and the patient raises their forearms up to their chest. It is caused by the same nerve signal that triggers us to snatch back our hands from something hot or sharp before our brain has had time to feel the pain. The brain plays no role at all. The cells sending the signal are in the spinal cord. Unlike the return of primitive reflexes, this motor response does not represent a cortical release. It can be the source of false hope and great doubt for families of patients whose diagnosis is brain death. It is known as the Lazarus reflex.

I couldn’t help but wonder if a part of Lucy’s drawings that day had grown out of her primitive reflexes, and if Dad’s drawings weren’t informing his remerging ones.

Dad waited to die until we were home in bed for the night. He looked hard at a nurse who came in to check on him some time after midnight. Thirty minutes later he was no longer breathing. There were no reflex checks, no respirator to detach. Dad died on Tylenol.

“Isn’t that something,” said my mother as we entered Dad’s room. She had spent years in hospice work. “Once the person is gone, the body is just a shell.”

I couldn’t see that. Death did not seem so instantaneous to me. His hands and cheeks were cooling, but when I stuffed my hands between his shoulders and the bed, there was still warmth, energy. I sat beside him like that, feeling the warmth that was still left and looking down into his face.

“He just marched right on out of there,” said my mother.

I was having a hard time leaving him. My sister chased an impatient undertaker away to the parking lot.

I couldn’t think of one reason to get up and leave Dad, nor why my reluctance was out of the ordinary. I pressed my forehead into his chest, an instinctive, familiar gesture. He exhaled with a sigh.

“Dad is making noises when I lean on him,” I said, like I was complaining that he was stealing my ice cream or had guessed the contents of a birthday gift before unwrapping it. My mother laughed, and for a moment the four of us were in bed together again.

The sun had been up for a while when I finally left to go pick up Lucy, now 4, from our babysitter.

We went home to the garden Dad had built and watched Lucy draw with chalk on the red brick. We sat there all day with blankets and looked at the woods like we were waiting for something.

Amanda Darrach is a journalist and filmmaker based in Brooklyn. She is a student at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism.

References

1. Hall, M. On the Diseases and Derangements of the Nervous System, in Their Primary Forms and in their Modifications by Age, Sex, Constitution, Hereditary Preposition, Excesses, General Disorder and Organic Disease H. Bailliére, London (1841).

2. Rademaker, G.G.J. Das Stehen Springer, Berlin (1931).

3. Bobath, K. A Neurophysiological Basis for the Treatment of Cerebral Palsy Lippincott, Philadelphia (1980).

Additional Reading

Fillit, H., Rockwood, K., & Woodhouse, K. Brocklehurst’s Textbook of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology Saunders, Philadelphia (2010).

Touwen, B.C.L. Primitive reflexes—Conceptional or semantic problem? In Prechtl, H.F.R. (Ed.) Continuity of Neural Functions From Prenatal to Postnatal Life Lippincott, Philadelphia (1984).