The R/V Falkor, the main research vessel of the Schmidt Ocean Institute, is normally on a very tight schedule. Researchers from around the world apply for time with the Falkor—which is outfitted with a remotely-operated underwater vehicle, or ROV, named SuBastian—to investigate places that would otherwise be difficult to reach. In 2020, the ship was slated to monitor low-light coral reefs in Australia’s North West Shelf, test out new seafloor imaging techniques, and explore the effects of a 19th century landslide near Papua New Guinea.

But when the Covid-19 pandemic started, a lot of these plans were cancelled or pushed back. In mid-April of 2020, the Falkor and its crew found themselves in Australia with a blank month on the calendar.

Robin Beaman, a marine geologist at James Cook University, was already scheduled to use the ship later in the year. The Schmidt Ocean Institute reached out to him to see if he could find the Falkor something to do in the meantime.

The resulting expedition, called “Visioning the Coral Sea Marine Park,” surprised everyone—because of the creatures and formations encountered, but also because of who found them. Scores of scientists and interested civilians were able to participate in the voyage from afar, thanks to the unusual research strategies required by these unprecedented times.

Rob Beaman (chief scientist): I have lots of ideas about where expeditions could go. They typically take years—from an idea through planning, grant-writing, all of that—to come to fruition. But we had literally a couple of weeks.

And so with that in mind, I pulled out an idea that I’ve had for a long time, which was to go out into the Coral Sea—specifically the Queensland Plateau, in the Coral Sea Marine Park—and map these thirty very, very large coral atolls, two of which are in the top twenty largest atolls in the world. We set out a plan over a month to basically do laps around each one of these thirty reefs.

Carlie Wiener (Schmidt Ocean Institute director of communications and engagement strategy): What’s most exciting about Australia is that all the dives that we’re doing are in waters that have never been looked at before. They have no dedicated science ROV in Australia, so all of this is new.

Kai Tea (PhD student in ichthyology, University of Sydney): This area [of depth] has traditionally been known as a twilight zone. It’s too deep for conventional scuba diving, and it’s too shallow for the RV submersibles. It’s very poorly known in terms of diversity and what lives down there.

Rob Beaman: It was a discovery-type science expedition, where you don’t really know what’s out there.

The Falkor has a crew of dozens: technicians, chefs, pursers and deckhands who keep things running, and who quarantined before castoff in order to safely live aboard the ship. Normally, the research scientists leading the voyage would also be on board, constantly meeting with each other and the crew to analyze, brainstorm, and plan. But the pandemic made this impossible. So—like many workplaces across the world—they had to move everything they could online.

Carlie Wiener: On this particular cruise, what was exciting was, the entire science party was remote, which we’d never done before.

Rob Beaman: No one had done this, right? Neither Schmidt or any of us. We just had to figure it out.

Deborah Smith (marine technician): A lot of the work went into trying to figure out how we were going to communicate with the science team every day—so they could feel like they were still there, and working on the data, but not on the ship.

Rob Beaman: At 8:00 in the morning every day, we would have a Zoom meeting. The master, the chief technician, the lead ROV person, maybe the first or second mate—they would be in the ship’s library. And then I’d be in my bedroom. The other principal investigators could join us from wherever they were in Australia.

Deborah Smith: The Falkor has a system that can show people both the cameras from the ROV, and different cameras around the ship. We can also display the computer screen of any of the systems on board. We ended up setting [Rob Beaman] up with remote computer access, to be able to watch the mapping as it was happening. That really helped him stay on top of where we were going.

Rob Beaman: I was at home with my family, and I could watch the ROV dive in real time. We’d set up an audio link, so when it was streamed to me, I could speak to it.

Deborah Smith: The Falkor has really great bandwidth, but one of those things that happens when you have an entire science team on board is you end up sharing that bandwidth with 16 more people. And so we were fortunate in a way that we didn’t have those extra 16 people trying to do their emails and Facebook and everything else. We were able to dedicate it more to science.

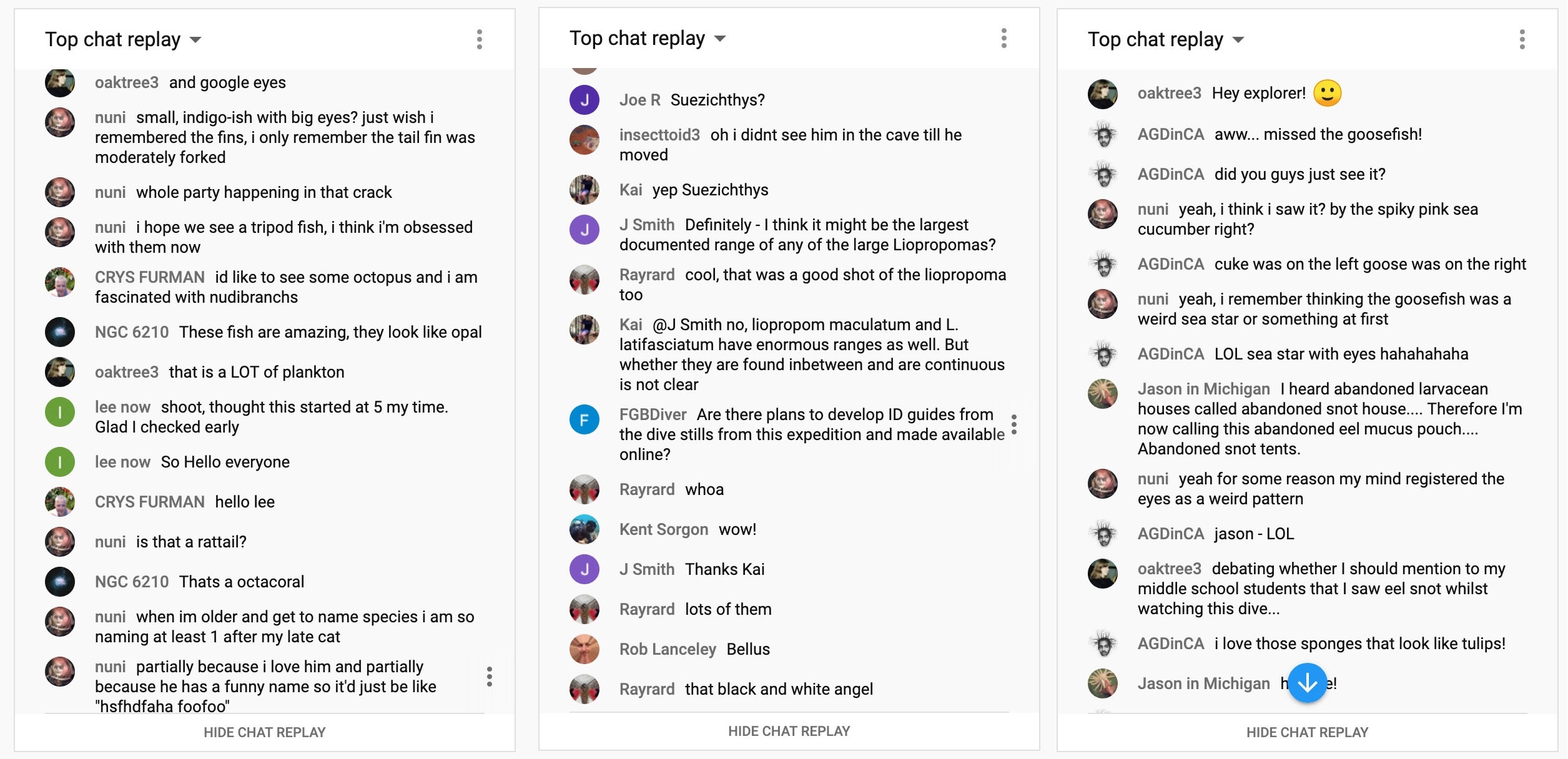

The Schmidt Ocean Institute publicly live-streams all their ROV dives—their version of open-sourcing. Anyone who wants to can follow along, chatting with each other and the voyage experts about what they’re seeing. This, combined with the remote protocols they had established for the core team, had an unanticipated consequence this time around: Scientists from all over the country could participate.

Rob Beaman: The voyage was streaming in real time. Outreach was important, to be able to let people know what we were doing and invite them in. That became an integral part of the voyage.

Carlie Wiener: I want to make sure we’re reaching as many people as possible. A lot of people have never gotten to see these areas before, and they live very close to the region. I also think with a lot of people at home during COVID, there’s been a hunger. When you’ve run out of all the things on Netflix, what do you look at next?

Lisa Price (livestream devotee): I started out [watching undersea livestreams], I think 2016 maybe. When I first found those, I was like, “Oh, this is fascinating.” I just got hooked on it.

I didn’t find Schmidt until December, 2019. It just popped up in my feed on Youtube. They had a chat open, and you could talk, ask questions, and the people on the boat were actually answering you. It just pulled me in.

Kai Tea: I kind of joined the expedition midway. I wasn’t following super closely because I was busy with other commitments. But I got tagged in a post [by people who had been watching the dives]. They tagged me because the RV submersible picked up a fish that nobody could identify, and they suspected it to be a new species of groppo.

Groppo are a group of fishes that are found exclusively in the supporting habitats within Australia. There are only two or three species that are known, and none of them looked anything like the one that was picked up on video. So I got really excited. I think that got back to Rob.

Rob Beaman: It wasn’t too difficult to just reach out to Kai and say, “Hey Kai, rather than just kind of do it on the side, why don’t you be part of the team?”

Kai Tea: I got all my fish friends and colleagues on Twitter really excited as well, and it just grew. Rob calls it the Fish Army.

Rob Beaman: I found this world of fish people. They’re very enthusiastic.

Then we brought in Daniela Ceccarelli, who’s a coral reef ecologist.

Daniela Ceccarelli (independent marine ecologist): If this expedition went on as normal, I probably wouldn’t have been on it. Usually for an expedition, you have to drop everything and just go out to sea. Being on the Falkor itself would actually be a lot harder for me than just being at home watching the ROV from the screen, because I get seasick. I’m one of the cursed marine biologists.

I’ve done a fair bit of diving on the Coral Sea shallow reefs, but I had no idea about the deep sea. None of us really did. That’s the blank patch on the map, for me.

Kai Tea: As the expedition progressed, we started seeing a lot of really cool things, like corals and nautilus, that were outside of our area of expertise. I told Rob, talk to Greg [Barord]. I’ve never met Greg in person, but we’re friends on Facebook, and I’ve seen him posting a lot about nautilus.

Greg Barord (research biologist with Save the Nautilus): I saw [the livestreams] on Facebook as well, just like lots of folks, and kind of watched. Then I got these nautilus questions from Kai who I’d never met.

Daniela Ceccarelli: There was this intense sense of collaboration—having these sort of virtual colleagues from all over the world tuning in. We get to just be nerds together.

Lisa Price: I’m a stay-at-home mom now. I have a degree in psychology. When I started college, I wanted to go to vet school, [or] be a marine biologist. I had some health complications, and they kind of put a stop to me being able to do those types of jobs.

I’ve learned to just keep a piece of paper and a pen next to me. And if I hear something I haven’t heard before, I write it down. Usually, if I see it two or three times, I’ll start to remember it.

I watch so much. I’ll be sitting there watching [another organization’s livestream], and the scientists are like, “What is this?” I’m sitting here screaming at the screen, wishing I could reach in there and tell them, [because] I’ve seen it like 900 times. It’s really cool being able to do that with Schmidt, because the scientists are watching, and I’m just in there telling them, “Hey, it’s so and so.”

Rob Beaman: When you go out on a deep sea oceanographic expedition, you start with a core group of people and hopefully you come back with the same number of people. But it never expands. Here, we were expanding.

For the scientists and others, watching the livestreamed dives was a way to explore and connect during a strange and homebound time.

Rob Beaman: We ended up doing 14 ROV dives, way more than we expected.

Carlie Wiener: I’m always interested in the dives. I have them on all the time. We’re having family dinners and my two-and-a-half year old is watching what’s happening.

Rob Beaman: It’s 4K vision, super clear. You can see what’s in front of you, but then you can zoom right down and look at tiny little amphipods growing on top of a sea cucumber which is sitting on top of something else.

It’s so addictive. It was riveting. Even grabbing a bite of lunch was difficult. I’d be buttering the bread, I’d have the audio going and they’d say, “Oh, there’s a such and such,” and I’d rush back.

Lisa Price: Anytime the divers go live, my son and my husband will go, “Oh, mom’s watching again, we’d better leave her alone.” And they both go in different rooms, and it’s just me on my phone looking at my screen.

On Facebook, I will post pictures if I see something really cool. And then, you know, friends will be like, “You really like fish.” And I’m like, “Yeah.”

Greg Barord: When you hear the term scientist, you might have preconceived notions of what that means. But we yell and scream and shriek just like everybody else when something cool happens.

Rob Beaman: You never knew what was around the corner. A giant isopod, or some weird pygmy octopus just drifting across the landscape.

Lisa Price: If I’m awake, I watch from the very beginning to the very end. It messes up my sleep schedule really bad—whenever they start going live there in Australia, I’m up all night.

Daniela Ceccarelli: There was this atmosphere of almost childlike suspense. And when something did pop up, it was really joyful. I had days when I had other things to do, but I would just be glued to the screen for like eight hours.

Kai Tea: There are tons of fishes in the sea, and I don’t know all of them. We got collections managers, experts from museums, really really keen hobbyists. It just grew into a really big collaborative project. Everybody was chiming in with ideas.

Rob Beaman: It was great to see the fish army. [One would] say “Oh, it’s this.” And then [another would] say “No, it’s missing a stripe on its left dorsal fin.” Something like that.

Lisa Price: On the chat, everyone is so nice. On the last expedition, we named the chatroom ’The Tether’s End.’ We’re kind of like Cheers, where everybody knows your name at the bar.

Deborah Smith: I love the deepwater dives, because I really think it’s amazing to see that much life in such a weird, barren place. But at the end of it all, I was like, “I don’t actually remember what we saw!” I think you get so focused on trying to execute the dive, and execute some of the technical aspects of it, you do miss it.

But ultimately I think my favorite thing is when we do get to see cool things—like some really cool squid, or the nautilus, or things like that. The crew really get excited, because we feed that video throughout the whole ship.

During the expedition, the Falkor mapped nearly 14,000 square miles of the coral sea, and shot 91 hours of video footage. The researchers, who have stayed connected, are now trying to figure out exactly what they found.

Rob Beaman: The 3D model we had of the coral sea before the Falkor went is this flat plateau, and these smooth edges rising up to the coral reef. But the very first map [by the Falkor] showed multiple ledges—big canyons enslicing into that, and these very large-scale underwater landslide features. Apart from just the joy of seeing the seafloor revealed for the very first time, straight away we’re asking, “How does this happen?”

And then of course the geology drove the biology. The synthesis of the mapping data leads to helping us understand what the shape of the seafloor is like, which leads to helping us understand what caused those features, which then links to the marine life that’s presently living there.

Attached to boulders and rocks, often from these landslides, were lots and lots of soft corals and deepwater, coldwater corals—slow-growing, long-lived marine life that don’t rely on any sunlight. It’s not a seafloor desert by any means.

Daniela Ceccarelli: There was a parallel with what we see in shallower waters, which is that when there’s a little bit more complexity in the geomorphological structure of the reef, there also tends to be more life.

I’m interested in patterns—are there patterns in the way that species are put together? If we saw the same kind of structure somewhere else nearby, would we expect the same species composition?

Kai Tea: We’ve gotten a lot of good videos and photos of not only [potential] new species, but also new range extensions and new records of fishes that have previously not been recorded from Australia. A lot of these represent really big geographical extensions. We’re seeing some fishes that were previously known to be endemic to Hawaii, for example, which is all the way across the Pacific. We’re also seeing a lot of fishes that are known only from dead specimens in jars and museums, that we’ve not been able to see in real life. We don’t really know their biology, or what color patterns they have in life.

We also have a lot of potentially new species. But this is a little bit harder to investigate. This part of the expedition had no fish sampling, so we can’t necessarily describe them as new species, but it gives us a good indication of what’s down there for future research and projects.

We are now working on writing a checklist of all the new species that we’ve seen, or the new records that we’ve seen.

Lisa Price: With the cephalopods and the snails, the echinoderms—I’m usually really good at remembering those because I really like them. It’s just fascinating to me that an octopus that has nine brains and three hearts, and the way that they move. They’re just really intelligent and fun to look at.

The corals, I mean, I can’t even—I can usually tell the difference between a bamboo coral and maybe a rock coral, but I’m still learning and there are so many different types. [A few years ago] I didn’t even know that corals were animals.

Rob Beaman: I loved looking at the nautilus. They are an amazing animal, so strange. They were very common—far more common than we’d expected. On nearly every dive we saw a live nautilus.

Greg Barord: The nautilus is found in quite a few places in the Pacific. But it’s so hard to research. It’s exciting to be able to see it in different areas. Just like the fishes, there’s different color patterns. If you see a specific nautilus, it’s a really good indication of where you’re at.

This whole kind of ecosystem, it’s considered the deep sea, but it’s really not that deep. It’s really pretty close to shore. I hope that it’s opened up this new area where people are like, ’Whoa, that’s that close?’

Kai Tea: We also saw a whole bunch of fishes that are just so weird, so bizarre-looking. It’s always exciting to see people on Twitter and YouTube and Facebook reacting to them.

We don’t even know stuff that’s living in our backyard, literally under our noses. You stick a video camera 200 meters down and you’re seeing all these things that you’ve never seen before. It really gives you a greater understanding and appreciation for what’s living down there.

The Falkor has since gone out on more expeditions, including a sister trip to this one, which involved many of the same participants. Although scientists are coming back on board, the researchers have tried to incorporate the same spirit of openness.

Deborah Smith: I think being able to bring in scientists that weren’t necessarily [originally] involved in the science team or collaborate with people from around the world really is what this technology is made for. It’d be interesting to really push the boundaries of getting more people involved.

Rob Beaman: It was really mind-expanding in so many ways.

Greg Barord: It’s really exciting to be involved in live research like that, whether you’re in person or whether you’re remote. I think this whole expedition showed the chances we have to expand research like this in the future. The benefits of it were so, I think, obvious—hopefully it happens more and more. If not to bring in more researchers, but to bring in more students, and more folks who may not see this at any other time in their lives.

Lisa Price: One of the science leads that was on the last expedition, he actually sent me a message on Twitter saying, “Have you ever considered signing up to come on the ship?” And, well, I don’t have a marine degree or anything. What in the world would you use me for? [He said] “Oh, you don’t have to have one. You really should think about it.”

Kai Tea: The tradition has continued into the second leg. It’s really good to see the same people still getting really excited, sending messages to each other, getting IDs. I’ve also been receiving a lot of photos and footage sent to me after the dives, because we don’t pick up all of it necessarily during the live video stream.

Rob Beaman: There’s 33 people involved in this expedition now.

Kai Tea: We’re not seeing people face to face. But we’re still able to connect in a different way.

Conversations have been condensed and edited for clarity.

Lead image: A Hollardia goslinei, or Hawaiian spikefish, encountered on the Falkor’s expedition to the Coral Sea Marine Park. Credit: Schmidt Ocean Institute