One night last month at Union Hall, a bar in Brooklyn, I attended a show put on by the Empiricist League (“A creative community for those who believe in evidence, observation, and experiment”) called “Mind Hacking.” The event description, on Facebook, consisted of a series of questions that I, in a contrarian mood, began to answer pessimistically: “In an increasingly divided world, how can we ‘hack’ our minds to cultivate traits like compassion and trust?” You can’t. “How do partisanship and group identity impact our ability to think and analyze, especially in our social media-driven world?” More than we’d probably like to know. “Can we train ourselves to be more rational and less capricious in how we approach the world?” Fat chance.

But it seemed like a fun evening. Jay Van Bavel, Director of the Social Perception and Evaluation Lab at N.Y.U., would be there, talking about the “dangers of the partisan brain.” As would Paul Bloom, psychologist at Yale and author of, most recently, Against Empathy, and David DeSteno, a psychologist at Northeastern University, where he directs the Social Emotions Group. Bloom would discuss how empathy smothers cooler, impartial forms of moral judgement, and DeSteno would reveal experimental evidence showing boosts in compassion from meditation. A friend of mine, a writer at Fortune, thanked me for the invite, saying, as we took our seats, “A gathering like this is my church.”

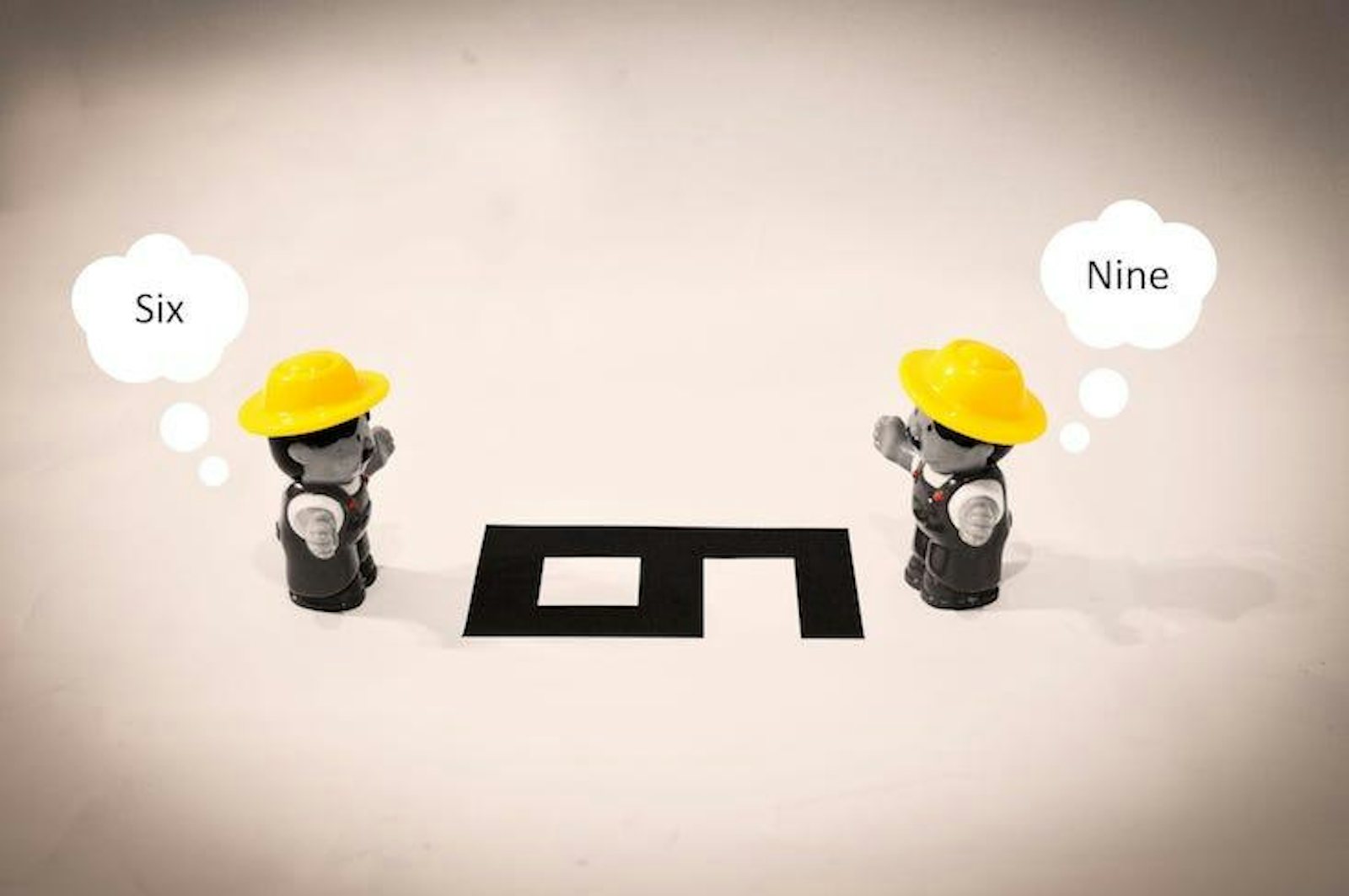

On stage, Van Bavel offered a little background. He said our psychology adapted to survive in a “socio-cognitive niche,” evolving many sorts of group-grounded biases—evident in sports—in what we believe and report witnessing. He then projected a photo on a screen behind him. Raise your hand, he said, if you think the crowd size on the left (at President Obama’s inauguration) has more people than the one on the right (President Trump’s). Everyone giggled as they raised their hands.

But it’s no laughing matter, Van Bavel said. Did we know that a political scientist, Brian F. Schaffner, posed the same question to a nationally representative sample of 1,388 adults in the United States, using the same image, in a study conducted within a week of Trump’s inaugural? A fifth, 20 percent, of the respondents got the answer wrong, choosing Trump’s crowd as the bigger one. That’s over 60 million people in U.S. population terms.

The supposed plausibility of a favorable lie makes spreading it seem less bad.

Trump voters made up 15 of that 20 percent, the other 5 percent being non-voters (3 percent) and Clinton voters (2 percent). That’s a “negligible” amount, Schaffner wrote in his paper, “essentially in line with what we would expect simply from measurement error,” like a subject accidentally clicking the wrong box. He found that the “difference in selecting the incorrect photo based on one’s vote choice or approval of Trump is statistically significant.“

How could that many Trump voters and supporters have gotten this wrong? Not because they were delusional, Schaffner wrote in the Washington Post, but because they were “expressive[ly] responding,” the term for “knowingly giving the wrong answer to support their partisan team.” Yet knowingly giving the wrong answer on this survey (as opposed to on national television, as the former White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer did) could in no way materially support Trump. “If a significant portion of Trump supporters are willing to champion obvious fabrications” in such cases, he wrote in his Post piece, “challenging fabrications with facts will be difficult” when it matters.

Part of the reason people champion obvious fabrications, or at least aren’t outraged by them, has to do with how the falsehoods are framed. Trump’s spokespeople, like Kellyanne Conway, imply that the crowd at Trump’s inaugural could have been bigger than Obama’s if only better weather had encouraged more attendance. “New research of mine suggests that this strategy can convince supporters that it’s not all that unethical for a political leader to tell a falsehood—even though the supporters are fully aware the claim is false,” Daniel A. Effron, a social psychologist at London Business School, wrote last month in the New York Times. In his paper detailing that work, he explained, “When a falsehood aligned with participants’ political preferences, reflecting on how it could have been true led them to judge it as less unethical to tell, which in turn led them to judge a politician who told it as having a more moral character and deserving less punishment.” The supposed plausibility of a favorable lie makes spreading it seem less bad.

Partisanship doesn’t just affect moral and perceptual judgments—even cold, quantitative reasoning can’t escape its pull. In the control condition of a 2006* study, mathematically savvy people were given an analytical problem to solve and aced it. However, when the problem was politicized—it involved comparing crime data in cities that banned handguns against cities that did not—math skills were no longer predictive. When the problem proved that gun control reduced crime, liberals solve it well, and ditto for conservatives when gun control proved the opposite. In a recent paper that begins, fittingly, with an ominous quote from George Orwell’s 1984—“The Party told you to reject the evidence of your eyes and ears. It was their final, most essential command”—Van Bavel and Andrea Pereira, a postdoc working in his lab, offer this takeaway: “In short, people with high numeracy skills were unable to reason analytically when the correct answer collided with their political beliefs.”

Looking to politics for social fulfillment is a recipe for subordinating your beliefs to the party line.

But resistance is not futile. Orwell himself had a reputation for overcoming bias. “His passion and generosity were rivalled only by his detachment and reserve,” Christopher Hitchens wrote of the great writer. Van Bavel, chatting with me over a beer after his talk, said that we could all learn to cultivate an Orwellian detachment. The “hack” was to enmesh yourself in a community where your social identity hinges on the accuracy and thoughtfulness of what you say, rather than on the ideological points you might score. He said “Science Twitter”—the many communities of scientists active on the platform who share and discuss their and their colleagues’ work—“is great at that.” Get something wrong, or take too much of an interpretive license with the data, and you’ll be chastised.

In their recent paper, Van Bavel and Pereira write, “To make this effective in a political context, it is necessary to determine which goals produce social value for an individual and fulfill those needs. When people are hungry for belonging, they are more likely to adopt party beliefs unless they can find alternative means to satiate that goal.” Looking to politics for social fulfillment is, in other words, a recipe for subordinating your beliefs to the party line. Social media—where many people consume political news and where falsehoods spread faster and deeper than the truth—feeds party-line beliefs and polarization. In a recent study of 2.7 billion tweets posted between 2009 and 2016, researchers found that “Twitter users are, to a large degree, exposed to political opinions that agree with their own.” This result is a “modern paradox,” Van Bavel and Pereira write. “Our increased access to information has isolated us in ideological bubbles and occluded us from facts.”

There are ways to defuse partisanship’s grip on your judgments. One is to reward people for accurate views. The authors write that “holding people accountable or paying them money for accurate responses can reduce partisan bias.” Priming people to adopt the mindset of “scientists, jurors, or editors,” can also help. Van Bavel and Pereira encourage us to foster a curiosity for science, “to seek out and consume science information in order to experience the intrinsic pleasure of awe and surprise.” A 2017 study found that it “promotes open-minded engagement.” “People with high levels of science curiosity seem to be more willing to consume news that is not in line with their political identity,” they write.

Granted, getting people to stay out of echo chambers and take a more passionate interest in science is no small request. So the best place to start might be with yourself. In a 2013 study, scientists found that people’s “mistaken sense that they understand the causal processes underlying policies contributes to political polarization.” Coming clean with how little you know could be the best way to overcome political bias.

Brian Gallagher is the editor of Facts So Romantic, the Nautilus blog. Follow him on Twitter @bsgallagher.

* This post originally linked to a 2013 paper when describing a control condition from an experiment that was actually part of a 2006 study. The 2013 paper cites the 2006 study.