On a late fall morning, Joseph Alexiou fastened his life jacket and stepped into an eight-foot fiberglass boat floating on the Gowanus Canal. A licensed New York City tour guide, and an amateur historian, Alexiou was preparing to take a passenger on an unsanctioned tour of the waterway he’d spent three years researching for his book, Gowanus: Brooklyn’s Curious Canal. Alexiou, 32, confessed that when boating on the canal, he felt slightly afraid for his life.

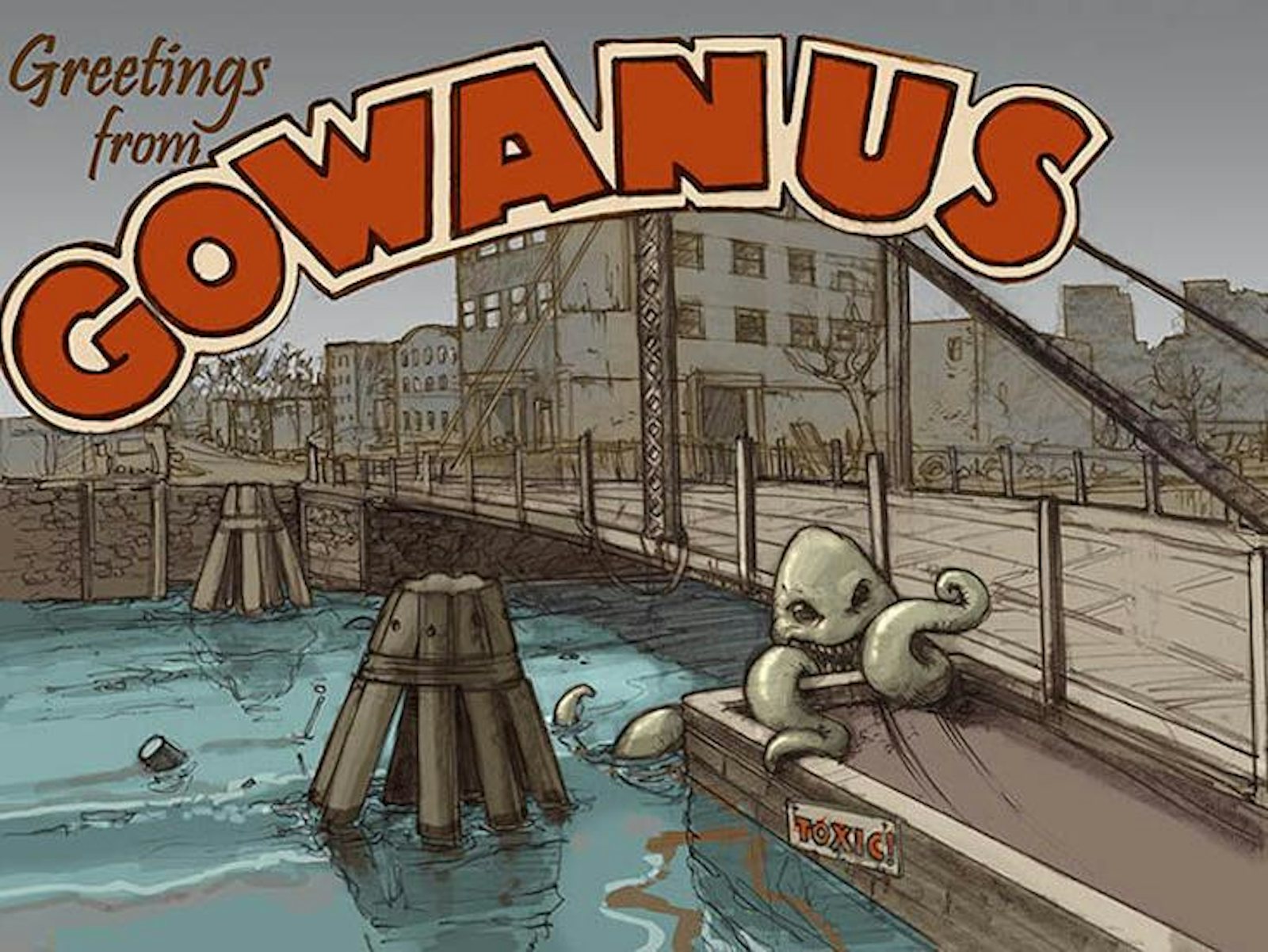

The rowboat pulled away from the rubble at the foot of Second Avenue, beside the new Brooklyn parole check-in office and across from Whole Foods Market. The water was milky green, with an almost oily thickness, and gangs of loose lumber blew crosswise in the wind. Alexiou took a picture of graffiti that said “Keep Gowanus dirty.” Then he began to rattle off, with apparent encyclopedic accuracy, the history of every building in sight.

In the 1800s, Brooklyn’s manufactured gas industry, which turned coal into gas (illuminating the city before electricity), had facilities along the Gowanus and became a major culprit in the colossal pollution of the 1.8-mile long canal. What’s more, the canal has always been a wetland, alternately draining and flooding the surrounding area. During heavy rain, untreated sewage pours into it from several points, the result of New York’s combined sewer and storm drain system and the canal’s low elevation. “Only the monumental, astronomically expensive effort of engineering could change this fact of geography, and so during the greatest rainstorms, swelling tidewaters fill the main and lateral sewer pipes,” Alexiou wrote in Gowanus. “Once these are full, the waters fill area basements—a fact of nineteenth-century life that continues today.”

In 2010, the canal was declared a Superfund site, authorizing the Environmental Protection Agency, and other government agencies, to clean it up. More than $500 million has been requested to combat 150 years of pollution. If you fell in, Alexiou said, you’d be treading in human feces and shower water. If you touched bottom, he added, you’d be stepping in “coal tar, PAH, PCBs, and heavy metals like cadmium, lead, and mercury—they call it black mayonnaise.”

The Fourth Street Basin, beside Whole Foods, used to be a dumping ground for dead horses.

Lately the canal has become an outdoor lab for a group of scientists, based at Genspace, a microbiology workspace in Brooklyn, who say they may have discovered new life forms in the snaking, oily sludge.

Their research began in the summer of 2014 when a team of volunteers and scientists paddled out in full HAZMAT regalia to sample the black mayonnaise from 14 sites on the canal, looking for a variety life. At Genspace, scientists extracted DNA was extracted from the muck and sent to the Weill-Cornell Medical College to be sequenced. In her lab, Genspace executive director Ellen Jorgensen smeared a dab of this sludge onto a slide and slid it under a dusty microscope. It smelled strongly of asphalt. “Fifty percent of the DNA we couldn’t identify,” she said. “It may be new,” as in, some life forms in the canal might be unknown to science.

What the Genspace-Cornell team did identify were 42 kinds of bacteria, two viruses, and five life forms from the domain Archaea, organisms that are not bacteria, fungi, plants, or animals. Many of these microbes are uniquely adapted to the canal’s extreme environment, and aren’t normally seen in healthy waterways. The Fourth Street Basin, beside Whole Foods, used to be a dumping ground for dead horses. Test results show that it’s now home to Methylococcaceae, a family of microbes that consume methane. The Gowanus’s signature rotten-egg smell comes from Desulfobacterales, which “breathe in” sulfate and “exhale” hydrogen sulfide. The sludge gets its black color from hydrogen sulfide reacting with metal ions.

As Alexiou wrote his book, he tried to remain objective but soon decided that contemporary city agencies and developers were, in his view, making the same mistakes as their 19th-century predecessors: ignoring the canal’s problems and failing to sustainably develop the surrounding area. “The more I became aware, I couldn’t sit there and be silent,” said Alexiou, who, from 2006 to 2011, lived a block away from the canal on Bond Street. He became an activist, protesting, meeting with community groups, and founding the Gowanus Preservation Society.

Given how polluted the canal still is, Alexiou feels that the pace and scale of development are irresponsible. The Superfund remediation is still in the planning phase; no actual cleanup has occurred yet. But Alexiou is not anti-gentrification. He likes bars with canal-front views, performance venues like the Bell House, and boutique art galleries like Site:Brooklyn—currently exhibiting winners of a Gowanus-centric design competition—as much as anyone.

The canal was so deadly that captains would allegedly pilot their boats through it to kill the barnacles attached to their hulls.

Elizabeth Hénaff, a microbiologist at Cornell who helped collect and study the sludge samples, was at Site:Brooklyn on a recent Friday to explain the winning project, which proposes to cultivate and accelerate the naturally bioremediating bacteria present in the canal. These microbes have evolved (at a rate of one generation every twenty minutes) to the point where they are consuming, she said, some of the Gowanus’s worst pollutants, like arsenic, fertilizer, solvents, and coal tar, a carcinogenic and insidiously durable byproduct of gas manufacturing. She is particularly excited about Pseudomonas putida, which consumes toluene, a neurologically damaging solvent used to produce paint.

A few oar strokes farther on, Alexiou pointed out a 19th-century brick sewer outlet—the reason many bacteria found in the human digestive system also live in the canal. Moraxella, linked to bronchitis and pneumonia, was found near the largest sewer outflow at the head of the Gowanus. Unspecified Enterobacteriaceae, the family containing Salmonella, Escherichia coli (E. coli), Yersinia pestis (bubonic plague), and Shigella (dysentery), were found throughout the waterway, along with Enterococcus, the signature bacteria of human waste. During Hurricane Sandy, shore-side buildings were inundated. “Is it responsible to build housing for lower-income people right next to toxic waste?” Alexiou asked, referring to another proposed project.

As we passed under the Carroll Street Bridge, a green johnboat with an electric trolling motor hove into view. The occupants were from Geosyntec, a company that consults on contaminated sites. They were downloading data from white floating devices that monitor groundwater welling up from the bottom. They handed Alexiou a green card reading “Wondering What We’re Doing?” and listing a website, gowanussuperfund.com, run by National Grid, a British company that operates the New York gas utility of the same name. The multinational is heir to Brooklyn’s 19th-century manufactured gas industry, and will be performing a portion of the cleanup at the EPA’s request.

Alexiou suspected that Geosyntec was measuring the movements of coal tar, which migrates slowly through the ground and along the canal bottom where, Alexiou said, the layer of toxins can be 10-feet thick.

Rowing back to the makeshift rubble landing at Second Avenue, Alexiou saw a cormorant—a dark-feathered aquatic bird—land, dive, and surface with something to eat. The activist-author was jubilant. For him, this bird, and the slimy plants wavering beneath the surface, is evidence that the canal can sustain more than just microbes. (Genspace volunteers also captured a live shrimp, which they named Mickey.) At least this much is different, Alexiou mused, from the days when, he was told, the canal was so deadly that captains would allegedly pilot their boats through it just to kill the barnacles and other sea life attached to their hulls.

With this thought in mind, Alexiou cautioned his passenger who, like himself was protected only by jeans and a light jacket, to disembark gingerly, to avoid a splash.

Tyler J. Kelley is a freelance journalist living in New York City. His feature-length documentary film, “Following Seas,” will premier at the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival on April 9, 2016.