In 1779 at the age of 10, William Scoresby Jr. attempted to stow away on his father’s whaling ship, Dundee, moored in the North Yorkshire town of Whitby, England. Historians would later write of his delight with this “floating mansion” and “its curious equipment,” and his “strange longing to participate in its progress and adventures.” His father, after discovering his son, was not angry and allowed him to stay aboard, and young Scoresby embarked on what became a life as oceanic adventurer, whaling captain, and scientist.

The whaling industry of Scoresby senior’s day was very much that; an industry, a brutal and barbaric trade and largely separated from the scientific endeavors and expeditions also occurring in the 19th century. After studying at the University of Edinburgh, Scoresby Jr. challenged this custom and undertook on his whaling voyages detailed scientific studies of the whales he caught and the Arctic landscape.

A lunar crater, part of eastern Greenland, and an early 20th century British research vessel would eventually be named for Scoresby Jr.; he appeared in Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, when Ishamael quotes Scoresby Jr. saying that “No branch of Zoology is so much involved as that which is entitled Cetology,” and describes him as “the best existing authority” on the subject of right whales. The much-beloved character of Lee Scoresby, aeronaut and explorer in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy, would be named after Scoresby, testifying to his ongoing legacy.

Recently whaling logbooks and narratives such as Scoresby Jr.’s have become valuable resources for contemporary scientists, informing projects like Old Weather: Whaling. Conceived between Zooniverse, New Bedford Whaling Museum, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the University of Washington, it uses data gleaned from historical accounts including whale catches, ice formations, locations and weather to give “ new clues about climate history.”

Statistical data is not the only source of valuable information. The illustrations that often accompanied texts—Scoresby Jr. was also a talented illustrator—can be useful in understanding how places and species were represented a pre-photo, pre-video age. Yet care must be taken when looking at this visual evidence; despite the veneer of scientific objectivity, it is far from neutral.

“One does not have to look far to see that if Scoresby Jr’s volume spoke of the natural environment of the Arctic, it did so in a culturally encoded language of national ambitions and aesthetic tropes,” wrote historian Benjamin Morgan in “After the Arctic Sublime.” Often liberties were taken to aestheticize certain realities via notions of the sublime and picturesque, and also would reflect a colonialist perspective.

Scoresby Jr.’s findings most notably resulted in the two-volume study An Account of the Arctic Regions: With a History and Description of the Northern Whale-Fishery (1820) and Journal of a Voyage to the Northern Whale- Fishery (1823). The first offers a history of the search for the Northwest Passage, a description of the Svalbard archipelago, tables of data and elucidations of sea, ice, atmospheric observations, and wildlife. The second recounts the history of the ‘whale fisheries’, discusses the classification of whales and catalogues the uses of whale bones and oil. It also includes anecdotes about fishing, descriptions of legal regulations, and mathematical models of climate and magnetism. The introduction to the 1969 reprint describes it as ‘a classic of whaling literature’ and an ‘outstanding pioneer work on the science of the sea.

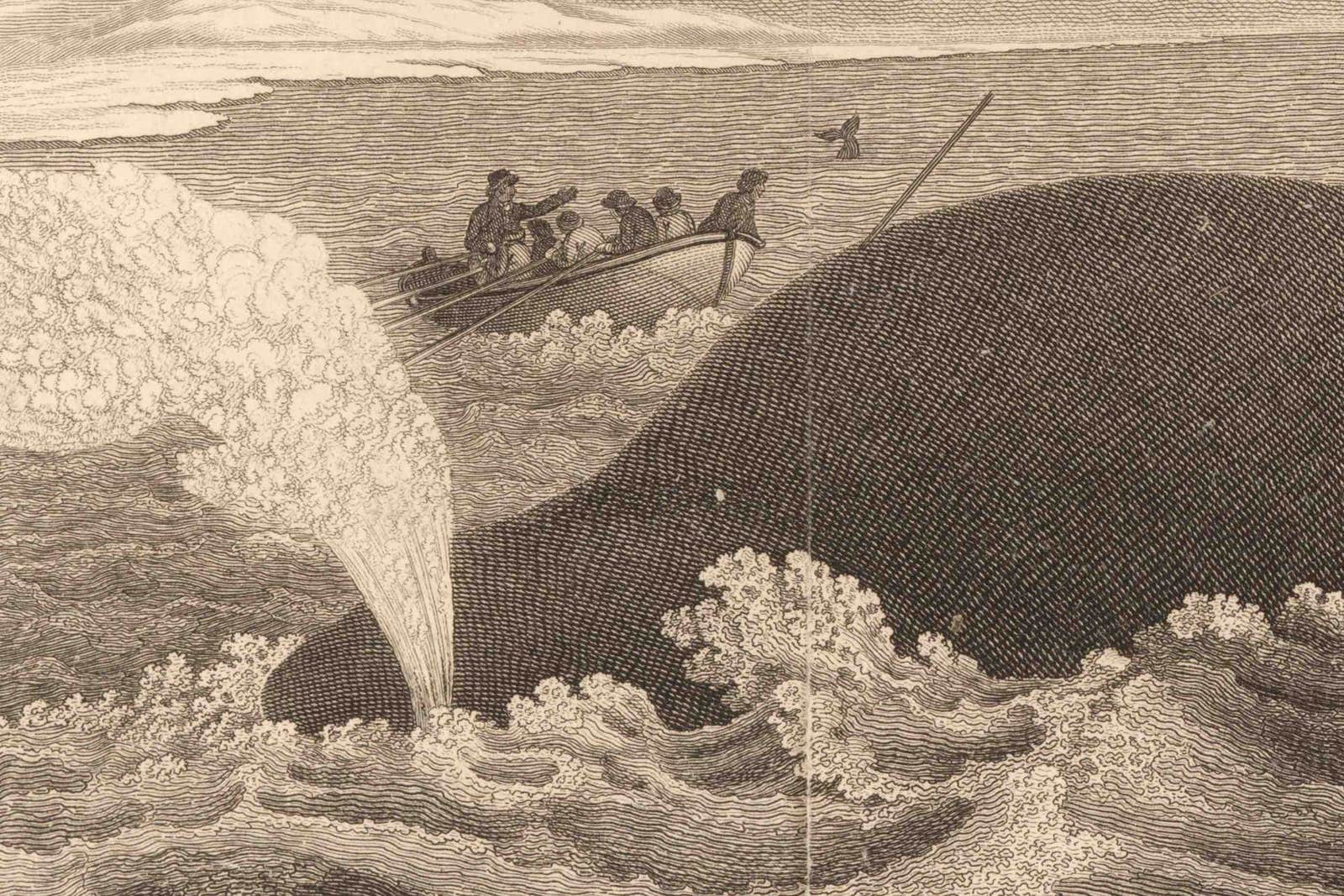

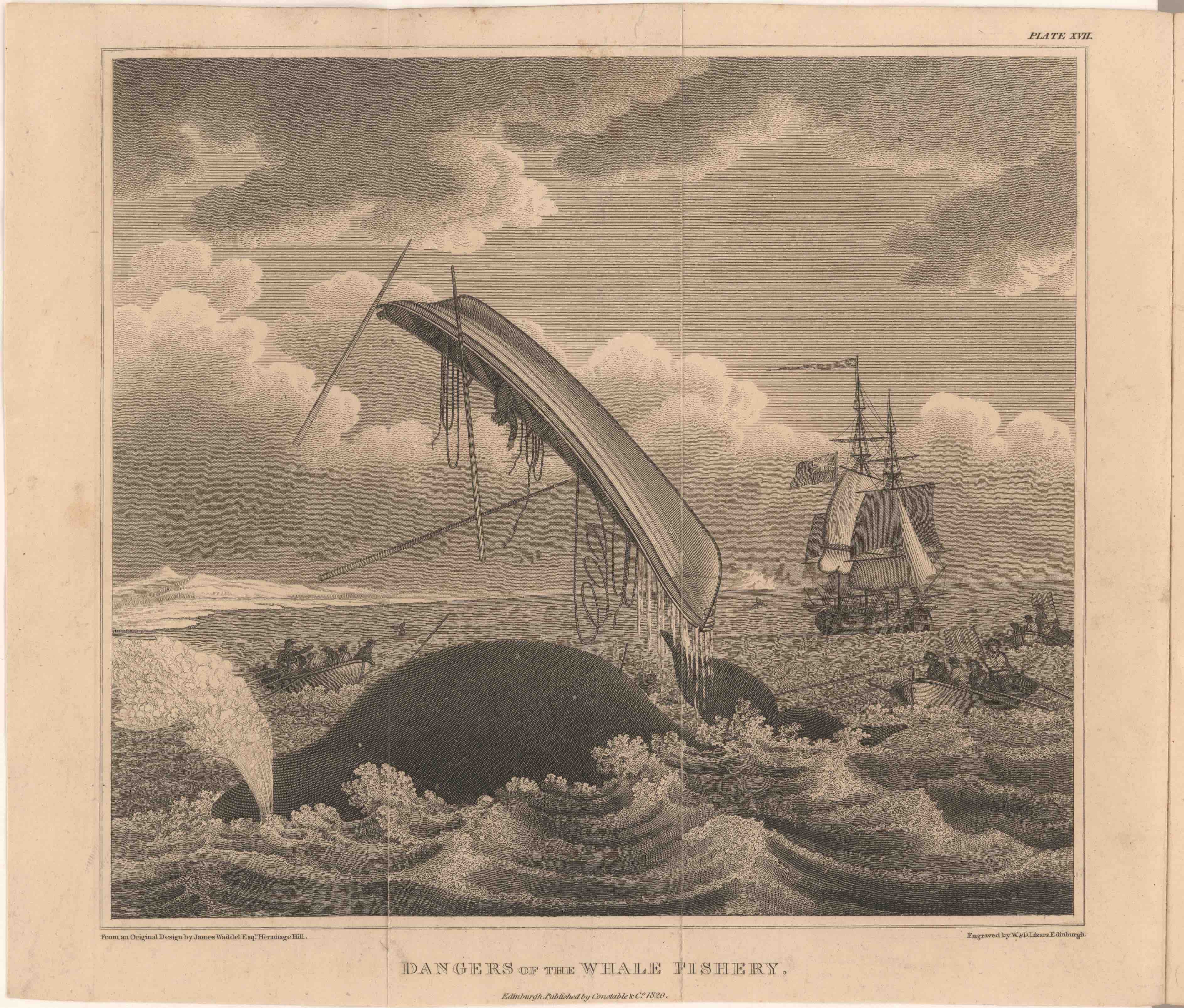

The first image that you encounter in the second volume of An Account of the Arctic Regions is a print, after an original drawing by James Waddel entitled “Dangers of the Whale Fishery.”

The scene shows an incident described by Scoresby Jr. in which a whale, struck with two harpoons, dove and resurfaced beneath a whaleboat, sending it flying in the air. All of the on-board crew were saved except one who could not free himself from the overturned craft. A bowhead or Greenland whale can be seen by its large bulk; a boat careens skywards; oars and string rain down; and a small figure of a man can be seen in this upturned boat, hand raised.

These elements of jeopardy, however, contrast with the stoic representation of the other whaling boats, one of which already has the whale harpooned, ultimately signaling which species is really in control. Visuals were often used in such scientific publications to create a sense of drama and prestige, often in contrast to the more rational use of data and statistics.

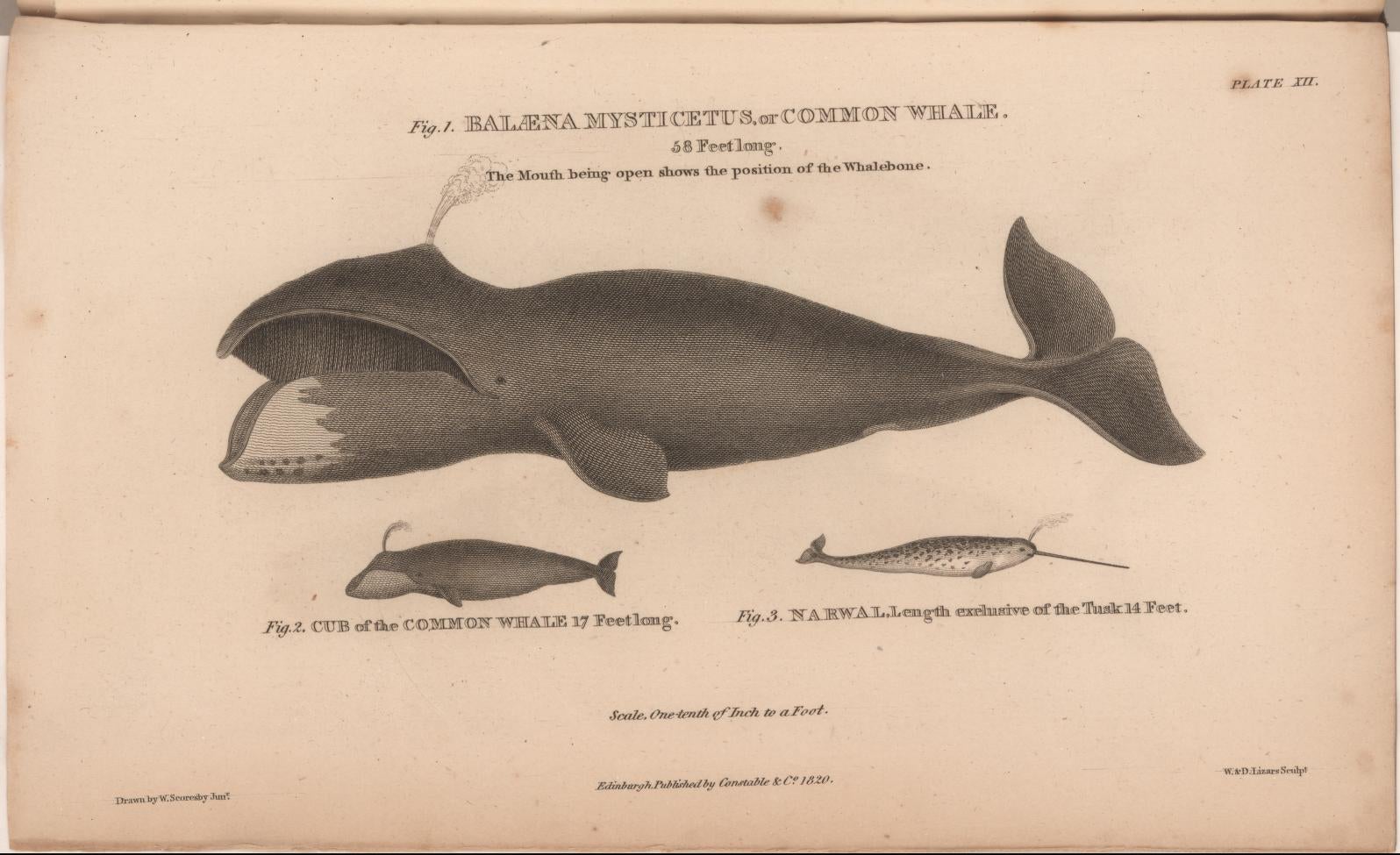

Another image of a whale is entitled “Balaena Mysticetus, or Common Whale 58 Feet Long.” Its mouth is slightly open, showing off the whalebone one of the bounties that whalers sought to take from the whales. Below are two smaller images,“Common Whale, 17 Feet Long” and “Narwal, Length Exclusive of the Tusk, 14 Feet.” Based on a sketch by Scoresby Jr., it shows the magnificent animals in profile, isolated on a white background, stretched out as specimens for observation. A scale of “one-tenth of inch to a foot” helps readers to envision the true size of the animals despite their reduction and reproduction within the book.

Scoresby Jr. comments on how ‘large as the size of the whale certainly is, it has been much overrated,’ by which it is ‘calculated to afford the greatest surprise and interest.’ Acknowledging the frequent miscalculation of whale sizes implies a certain accuracy to Scoresby Jr.’s own work, assuring readers that his account is fact-based. The whales depicted are clearly still alive, as they spout water from their blowholes—yet they are shown inflated to a degree that would greatly differ from the reality of a whale out of water, who would be deflated and flaccid. This style of representation was and continues to be popular in natural history representations of whales.

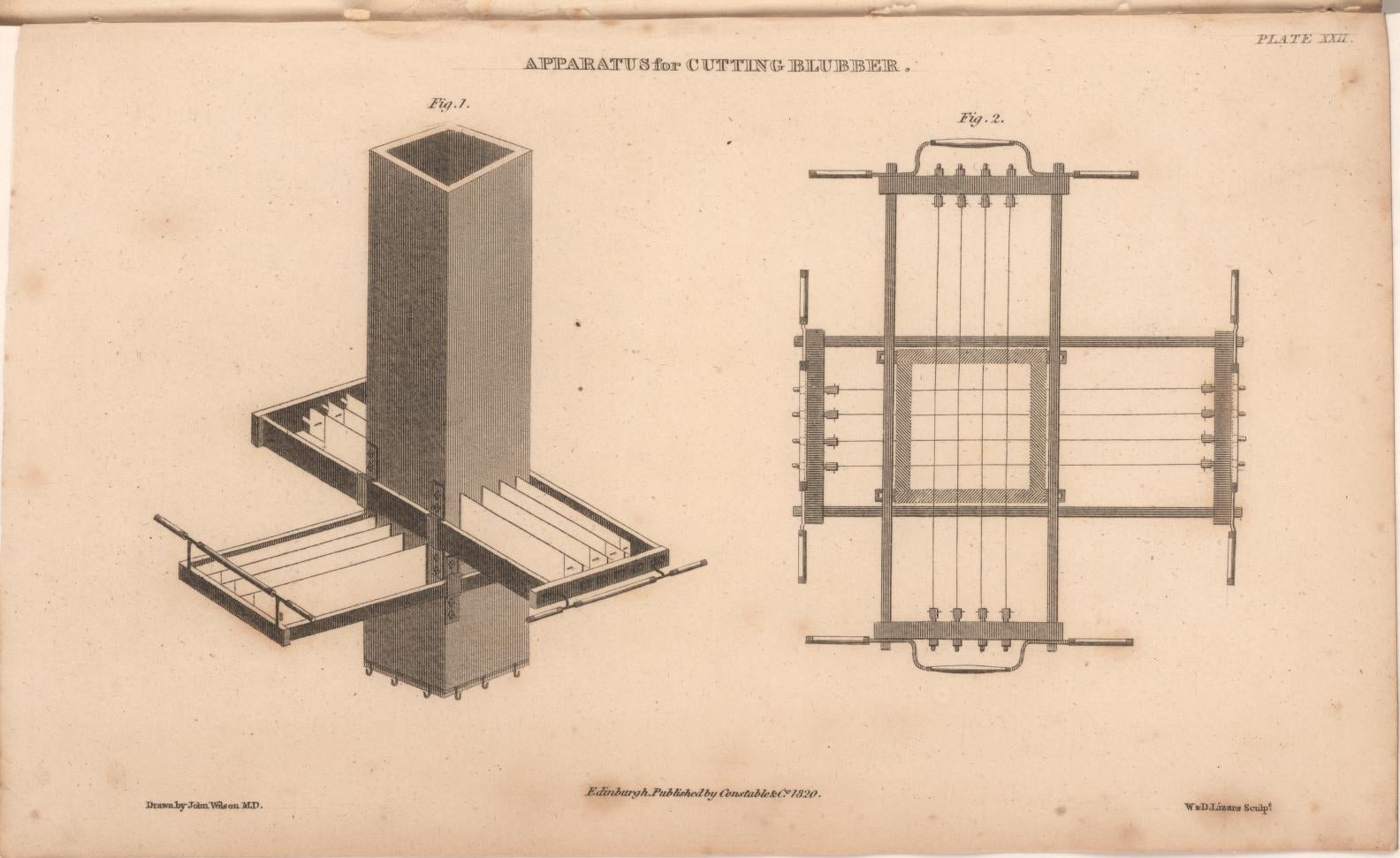

The book’s last image is a highly industrial-looking object that allowed for the more precise removal of flesh from a whale’s body. Scoresby Jr. describes it as

‘an excellent apparatus for cutting blubber […] When it is in use, the blubber to be cut is put into the tube at the top, and falls upon the edges of the knives. The knives are then put into rapid horizontal motion, by which the blubber is readily cut into proper sized pieces, and falls into the lull attached to the bottom of the machine.’

By ending with this illustration, the reader’s final impression of whales is literally an object of industrial interest. The butchery of an animal, of entire species, is transmuted into a bloodless mechanical process. This cutting and categorising the animal for sale resonates with the taxonomies alongside which Scoresby Jr.’s journals would often be filed, digesting the natural world into more manageable chunks.

How are such illustrations valuable for science today? Despite the aestheticization and inaccuracies, Scoresby Jr. offers a record of species and a place. They complement the statistical data he captured and offer visual documentation. They point to the evolution of science, how it was collected and disseminated—but they demand of contemporary viewers a rigorous critique of the narratives entangled within.

Images are not always neutral, even within the framework of science. What narratives go unexamined today in contemporary scientific imagery? What might seem strange and even objectionable at a few centuries’ remove that is now taken for granted? The work of William Scoresby Jr. challenges us to ask.

References

1. Tom & Cordelia Stamp, William Scoresby: Arctic Scientist, (Caedmon of Whitby Press: 1975), 6.

Lead image: Dangers of the Whale Fishery – Detail from William Home Lizars after James Waddel, “Dangers of Arctic Whaling,” in An Account of the Arctic Regions Vol. II. Edinburgh: Archibald Constable and Co., 1820. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library