During a career spanning 25 years, Cristina Mittermeier has photographed bowhead whales in the Arctic, sea turtles in the Galápagos and an awe-inspiring array of marine wildlife in the oceans in between. She spoke to Five Media about the urgency of protecting the beautiful undersea world—much of which remains to be explored.

What is it about the ocean that attracts you?

From an early age, maybe because of what Jacques Cousteau was doing for National Geographic, it was so obvious to me that our planet is an ocean planet—that this is the ecosystem that allows life to exist, so how could I not be fascinated by that? I think we all should be!

What’s your earliest memory of the ocean?

I grew up in the mountains of central Mexico, but my father was from Tampico, a small city in the Gulf of Mexico, which is part of the oil infrastructure along the Mexican coastline. We’d go visit my grandma and the beach and my earliest memories are of being taken by this massive wave, tumbling and coming out exhilarated. But my next memory is of my mother cleaning the tar off our feet because the beach was so polluted from the fossil fuel industry.

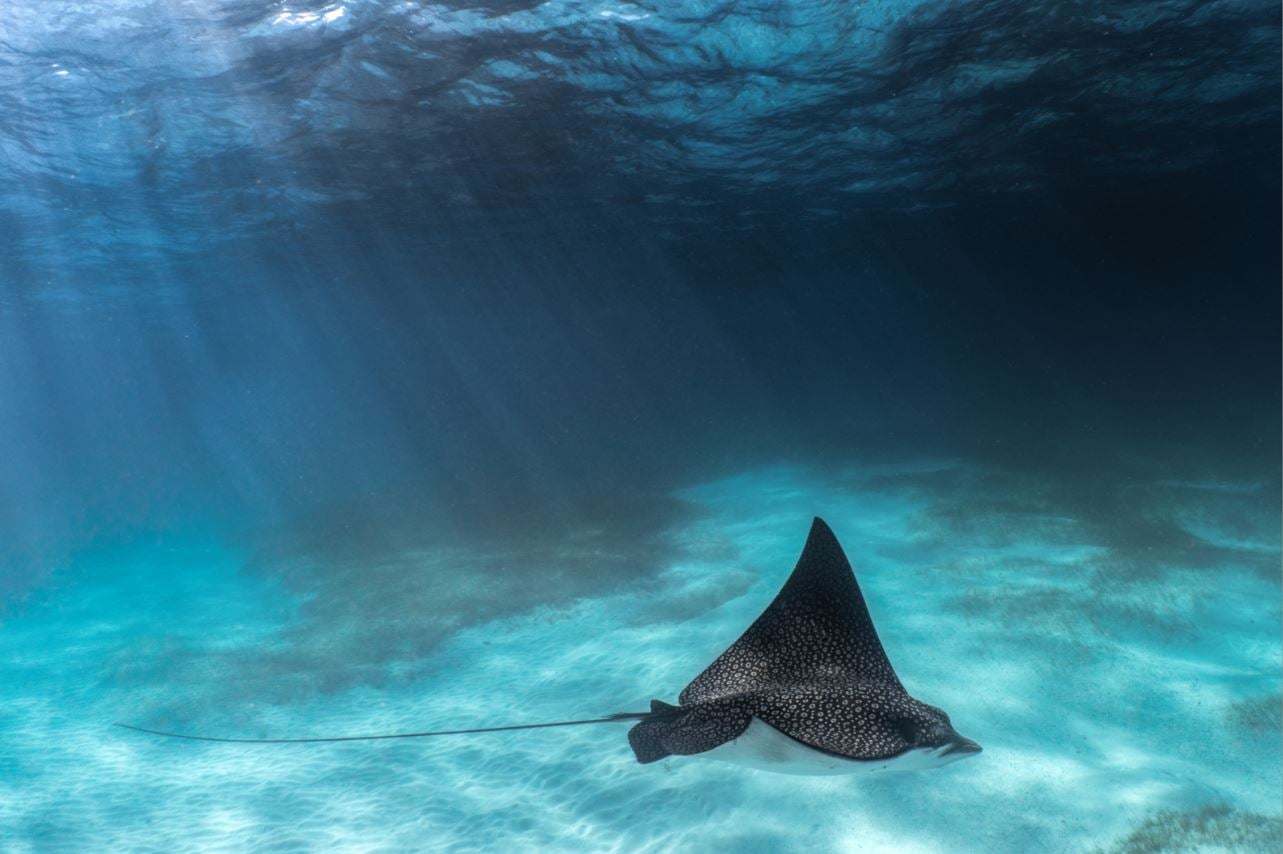

“You just have to put the camera down and marvel. There’s over a million years of evolutionary perfection out there.”

Your most memorable marine wildlife encounter?

I have so many! Usually it’s the most recent one. We just spent five days swimming with eagle rays. There must have been 100 of them following a large female in big circles—all in just nine meters of water. They’re simply mesmerizing. They have a dotted pattern on their dorsal area and it feels like an artist took a lot of care designing something so fragile and exquisite. They come close to you and you just have to put the camera down and marvel. There’s over a million years of evolutionary perfection there and we know nothing about them. There are secret pockets of the ocean where these things are still happening.

Every time you go down, you see something you’ve never seen before. We get these little glimpses of the ocean and its creatures but it’s so big and it’s so unexplored and, shockingly, it’s the Sustainable Development Goal that’s the most underfunded. As a scuba diver, my tank is what keeps me alive. I don’t neglect it because it’s my next breath. The same goes for our oceans. It’s the life support system of this planet. We need to understand and protect this thing that keeps us alive.

When people say that 50 per cent of the oxygen from the planet comes from the ocean—it doesn’t come from the water. It comes from the cocktail of creatures in this living broth that is creating the chemistry of our planet.

You’ve set up organizations that bring photographers together around conservation. What drove you to do that?

I could see that the photographic community didn’t recognize itself as a force for conservation issues. Nobody was asking how we can use our images to further the cause of protecting the planet. So I started the International League of Conservation Photographers, even though I was still a mom of three children—a housewife working from my basement and thinking: what do I know about starting a non-profit organization?

But running a non-profit meant that I neglected my own conservation photography work. When I was able to start shooting for National Geographic with my partner and fellow photographer Paul Nicklen, we were on the frontlines, seeing exactly what’s happening to our oceans. I felt like we needed to let the world know that the ocean is in trouble.

SeaLegacy [a collective of photographers and filmmakers working for healthier oceans] allows us to speak directly to the people that follow our work and give them the opportunity to take action and be part of the solution. I think young people crave that.

What can people do?

A lot of people want to do the right thing but don’t know how. We want to make it easy for them. So we launched a new action platform, Only One, as part of SeaLegacy last year. We have a big menu of actions. Sometimes it’s signing a petition or adopting coral, restoring a mangrove or supporting research. And it’s working. It’s a matter of learning about the problems, understanding the solutions and giving people an opportunity to act. When people see that it’s making a difference, they want to do more.

“We’re seeing the rise of a global movement of young people demanding a living planet.”

What gives you hope?

I could not have said this 10 years ago when things felt really hopeless, but now we’re seeing the rise of a global movement of young people demanding a living planet. I feel hopeful that there’s still a window to turn this around. COVID has taught us that our planet is interconnected. That we are very vulnerable and need to rely on the natural world. I think we’re having a unique moment. It’s now or never.

Lead image: A lucky encounter with a blue whale on a dive in the Azores.

Reprinted with permission from Five Media.