Scientists have now produced apparently effective vaccines at sufficient scale to vaccinate most vulnerable populations in the United States in the next few months, and the U.S. population more broadly in the next year. How can the distribution protect the masses without perpetuating inequalities? There are no simple answers but the way forward must be informed by understanding the complex interactions among the virus, vaccines, individual health and socio-economic status, and the societal structures in which these are all embedded.

COVID-19 has exposed complex racial injustices in a medical system that aims to protect as many people as possible, but often fails to protect the most vulnerable. Epidemic models that don’t account for structural racism and other social determinants of health result in policies that perpetuate inequality, even as they reduce disease transmission in the general population. Disparities in disease spread and mortality as well as inequitable disease treatment and access to testing have become increasingly evident in the growing pandemic.

An early analysis of COVID-19 showed the elderly had a 15 percent mortality rate, and it was three times higher for people with comorbidities. We counted up the comorbidities in our immediate families (hypertension, diabetes, kidney disease, heart disease, dementia, sickle cell trait, asthma), and realized the extreme risk they faced. One of us has a sister with Down Syndrome—a condition we later learned carries 10 times the COVID-19 mortality of the general population. She lives with elderly parents and loved her job at the local grocery store until she had to leave it to protect the family from exposure to a likely deadly disease. The tragedy became even more real when one of us lost a relative who had comorbidities to COVID-19.

In May, we wrote about the dramatically higher rates of disease and mortality in the black and brown population in the U.S. As scholars of human rights and complex systems science, we asked what caused this disparate impact of COVID-19, why epidemic models did not predict it, and what could be done to address it. Like many African-Americans, we fear for our loved ones with comorbidities that put them at extreme risk. Unlike most African-Americans, our families have the means to leave high-exposure jobs and to work and attend school from home.

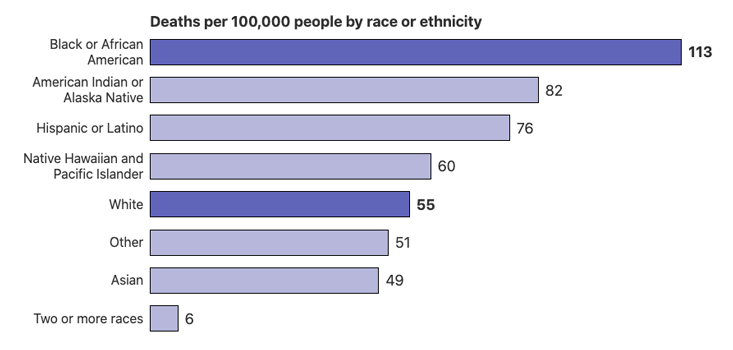

Throughout this pandemic, our personal struggles to care for our families grew into increasing alarm for the health and economic risk to communities of color. Now, in November, we know that African-, Latinx- and Native Americans are hospitalized for severe disease at four times the hospitalization rates of white Americans. Per capita death rates from COVID-19 are twice as high, and when adjusted for younger populations and reduced lifespans they are 3 times as high for African- and Native- Americans than white Americans.1 Contrary to the narrative that COVID-19 is a disease that predominantly kills the very old, more people die in their 50s and 60s than in their 70s or 80s on the Navajo Reservation. Even as the virus spreads broadly across the US, communities of color continue to suffer more death and disease at younger ages.2

As scholars of human rights and complex systems science, we ask what causes the disparate impact of COVID-19.

Myriad explanations for racial differences in COVID-19 exposure and mortality have been proposed, particularly focused on the work circumstances, living conditions, health status, and health care access among African-Americans, who tend to live in denser urban areas and multi-generational households, and to be essential employees who cannot work from home. We are likely to have less paid sick leave and health insurance, but more underlying medical conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, sickle cell disease, asthma, and exposure to pollutants that elevate COVID-19 mortality risk. The severity of our medical conditions are often underestimated and dismissed by the medical system.

Higher COVID-19 mortality is consistent with other health disparities in African-Americans: a four-fold greater probability of dying from complications during childbirth, 20 times greater chance of heart failure before age 50, and a four-year shorter lifespan. The stress of living under the threat of racism appears to age black bodies faster than white ones. The multiplication of many inequities over time results in larger gaps over time, just as black income is 60 percent of white income, but black wealth is only 10 percent that of whites.

Native American COVID-19 risk is also influenced by extreme inequity in health and economic circumstances, including lack of services as basic as running water and inadequate federal funding of health care. In the first wave of the pandemic, the Native population was a staggering 17 times more likely to be diagnosed and over 10 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than the white population in New Mexico (one of the few states reporting sufficient data to make such comparisons at the time). Historically, previously isolated Native populations were decimated by diseases upon European contact centuries ago and were also four times more likely than others to die in the 1918 flu pandemic. COVID-19 threatens the very survival of small Pueblos like the Zia with fewer than 1,000 members. Given this history and the concern that COVID-19 could decimate their populations, many tribal governments closed public access, sometimes facing threats to their sovereignty by the governors of surrounding states.

The socioeconomic factors correlated with COVID-19 vulnerabilities are the manifestation of hundreds of years of structural racism that has left formerly enslaved and colonized populations with poor physical and economic health and often in spatially segregated places. How do epidemic models incorporate these racial and socioeconomic realities? Thus far, they don’t.

Initial epidemic models, and most that still influence pandemic policies, assume “well-mixed” populations. More sophisticated network models consider different categories of people and their risk of infection and mortality, and some models recognize that the most vulnerable socioeconomic groups are invisible in their datasets. However, few of these studies consider how mobility and vulnerability depend on the racial and socioeconomic make-up of different places. Far more work is needed to incorporate systematic correlations among epidemic factors within particular groups in particular places. More often, people are modelled like identical balls bouncing randomly in a lottery machine, equally likely to contact infection, become sick, infect others, or have their number drawn as the unlucky one to die. However, people are not equally vulnerable, and America is not well mixed.

One of the greatest determinants of physical and economic health is the zip code in which you were born. Zip code is a powerful predictor of the chance that you go to prison or college, that you will live past 70 or die early from heart disease, whether you will drive a bus or work safely at home. Like wildfires that burn where the winds blow and the grass is driest, the spread of disease is determined by a template of risk and vulnerability laid out in physical space. In America, that space is largely determined by race.

Zip code has long been used as a proxy for race. Redlining was the deliberate practice of denying black Americans access to safe neighborhoods with high property values and good schools. Now zip code is used in algorithms that determine where predictive policing is concentrated and eligibility for loans and higher credit. The spatial segregation of Native and African-Americans have different historical causes, but similar consequences are clearly visible in COVID-19 mortality maps. The zip codes, counties, and territories where African- and Native Americans are concentrated have been the deadliest places in America.

Disease spread is an inherently multi-scale spatial process. It is caused by the entry of a nanometer-sized virus into a cell, where the probability of that infection is influenced by the space in a crowded factory, nursing home or prison, by the availability of healthy food or air pollution in a neighborhood, and by the social structure of a nation that determines the level of stress, inflammation, and cardiovascular health of the body that cell inhabits.

What are ways to protect the most vulnerable people in the most vulnerable places? Disparate impact matters not just for predicting who is at risk, but also for prioritizing who is tested, isolated, economically supported, treated, and vaccinated. As in civil rights law, disparate impact needs to be addressed regardless of how complex its causes or whether there is discriminatory intent. How can our response to this disease increase the resilience of the most vulnerable populations to the next pandemic, the next economic shock, and the looming climate crisis?

How can communities of color trust a vaccine produced by a medical system that continues to discriminate?

COVID-19 racial and ethnic health disparities are the new frontier of human rights in the United States and globally. The international efforts in reparations for human rights violations provide a framework not just for redress of past injustices that have led to increased community risk from COVID-19, but also for forward-looking provision of free access to community health initiatives located specifically in the places where the most vulnerable populations live. COVID-19 maps show us where those places are.

A complex systems approach to addressing past inequities would consider the historical, layered, and interacting factors that may be impossible to disentangle but collectively put certain populations at highest risk. The goal is not just to repair harm, but to spur a concerted effort to make people and places less vulnerable to this pandemic and the next one: lowering rates of diabetes, increasing access to healthy food and caring doctors, reducing air pollution. Such systemic changes support resiliency to survive disease outbreaks in the places we already know are most vulnerable.

Complex systems thinking led to powerful models that informed policies early in the pandemic to mitigate COVID-19 growth in the general population. While it is necessary to reduce COVID-19 broadly in order to shield the most vulnerable from infection, it is not sufficient. The simplifying assumptions that allow for powerful broad scale predictions are only a starting point. Models need to incorporate the systematic and structural features of societies that determine how both policies and physical space mediate disease spread. Similarly, they need to account for economic inequities that make it so difficult for many people to protect their families from disease while still putting food on the table.

Models simplify a complex reality in order to gain insights. However, modelers and policy makers must remember that viral spread is not an idealized mathematical process taking place in a vacuum. COVID-19 disease is an emergent phenomenon whose spread and severity is a consequence of the properties of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the age, health, occupation, and socio-economic status of individuals, and societal structures which cause disease to spread differently among different people in different places for different reasons.

Just as epidemic modeling should consider the varied impact of disease and economic policies on different populations, vaccine strategies must consider variation in people’s ability to be vaccinated and their trust in the system offering vaccines. In addition to prioritizing vaccines for the elderly, disabled, and those with comorbidities, they must also prioritize those essential workers whose risk has enabled the rest of us to work safely at home. This means granting first access to vaccines not just for health care workers, but also for bus drivers, factory and farm workers, and people who bag purchases at the grocery store. These (often immigrant, black and brown) service workers are underpaid and have little ability to take time from work to wait in line for a vaccine or take a day off from side effects. The lack of paid sick leave for essential workers is a national disgrace. Will we at least offer vaccines conveniently in the places where the most high risk populations live and work?

Vaccination in communities of color presents a conundrum. A history of unethical medical experimentation is rooted in slavery and exemplified by the unethical Tuskegee syphilis experiments that withheld treatment for African-Americans for decades (1932-1972). Unethical medical treatment continues today in inadequate access to health care, denial of health services, and other forms of structural racism in the medical system.

A truly effective vaccination program must protect the most vulnerable communities.

In the past few years, Serena Williams nearly died from the inability to get proper post-partum care, immigrants of color suffered sterilization without consent in detention centers, and African-Americans were denied kidney transplants by formulas that deliberately put them at the back of the line.3 Such systematic denial of medical care has continued through the COVID-19 pandemic with African-Americans being denied adequate testing, misdiagnosed, and turned away from hospitals.2 While efforts at the local level have shown that simple measures can reduce COVID-19 disparities, the lack of a coordinated national effort to address COVID-19 racial inequities sends the message that black and brown lives do not matter.

When centuries of experimentation and denial of care continue into the current pandemic, how can communities of color trust a vaccine produced by the medical system that continues to discriminate? In fact, they do not.4

Distrust of a biased medical system will cause communities of color who are most at risk for COVID-19 to be least likely to choose to be vaccinated. Many in communities of color view the opportunity for vaccination as ploy for further unethical, unconsented medical experimentation, particularly if they are offered it first. The problem is exacerbated by political intervention in treatment authorizations, drug approvals and vaccine programs that are dubbed “warp speed.” The complexity of harms that lead to disproportionate exposure rates, infection rates, and death also limit social trust in new vaccines that might mitigate these risks in the future.

Early in the pandemic, myths spread on social media that people of African descent could not contract COVID-19. Now, myths spread that vaccines are designed to kill black people. Trusted messengers must counter these lies, while also acknowledging that the lies are rooted in a system that is untrusted for good reason.

Vaccine messaging must clearly and transparently communicate vaccine effectiveness and safety, as well risks and limitations that are not yet fully understood. A small percentage of the population has been allergic to past vaccines. Who will be most at risk of negative reactions to COVID-19 vaccines, and which of the many vaccines in development are least likely to cause allergic reactions? So far, vaccine trials have measured only the ability to reduce symptoms and severe disease, not the ability to reduce transmission. We do not know if vaccination can lead to “herd immunity” until controlled studies test that assumption. Could large numbers of vaccinated asymptomatic carriers actually increase risk for immune-compromised people who cannot be vaccinated? Will society adopt policies that limit travel5 or work opportunities for those who cannot be vaccinated, even before there is evidence that vaccination reduces COVID-19 transmission? What will happen for the billions of people around the globe who must wait years for a vaccine to be available? Will efforts to curb disease spread exacerbate existing global inequities, eliminating the rights to travel and work for those already most vulnerable?

Decisions about how and when vaccines are distributed should be made in consultation not only with public health experts representing diverse communities, but also with sociologists, historians of science, and other experts who understand the complex history and contemporary manifestations of medical discrimination and distrust in communities of color.

Additionally, information about vaccine benefits and risks must be delivered by trusted community members. Black doctors, church leaders, tribal leaders, and celebrities of color should be enlisted to communicate to their communities. Additionally, we must communicate the contributions of people of color to the creation of COVID-19 vaccines. Kizzmekia Corbette, Ph.D, an African-American woman, is the lead NIH scientist who developed a key biomedical innovation to make vaccines that are highly effective at preventing disease and can be rapidly produced. Her achievement should help African-Americans recognize that this is our vaccine too. Countless lives will be saved by her brilliant research and, before her, the contributions of others like Charles Drew, who made large scale blood banks and blood transfusions possible. While discrimination in health care and biomedical research is real, African-Americans, and all Americans, should know of and appreciate African-American scientists who have developed life-saving biomedical innovations.

It is simultaneously true that the U.S.medical system at its worst contributes to disparate COVID-19 health outcomes and mortality, and at its best has produced apparently exceptionally effective vaccines that will reduce COVID-19 symptoms and disease. Looking forward, a truly effective vaccination program must be part of a much broader medical and public health system that protects the most vulnerable communities. It is time to begin recovery not just from COVID-19, but from centuries of inequity in American health care.

Melanie Moses is a professor of computer science and biology at the University of New Mexico and an external faculty member of the Santa Fe Institute. She builds computer models of how the immune system responds to viral lung infections and studies other complex adaptive systems.

Kathy Powers is an associate professor of political science at the University of New Mexico, adjunct faculty at Georgetown University and a Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars in Washington, D.C. Her research focuses on using quantitative and qualitative methods to study the politics and law of human rights, trade, and political violence.

Both are members of the Interdisciplinary Working Group on Algorithmic Justice.

References

1. APM Research Lab Staff. The Color of Coronavirus: COVID-19 deaths by race and ethnicity in the U.S. apmresearchlab.org (2020).

2. Keating, D., Eunjung Cha, A., & Florit, G. ‘I just pray God will help me’: Racial, ethnic minorities reel from higher COVID-19 death rates. The Washington Post (2020).

3. Simonite, T. How an algorithm blocked kidney transplants to black patients. Wired (2020).

4. Wan, W. Coronavirus vaccines face trust gap in Black and Latino communities, study finds. The Washington Post (2020).

5. COVID: Vaccination will be required to fly, says Qantas chief. BBC News (2020).

Lead image: IM Vector Studio / Shutterstock