A newborn is circled by her fascinated siblings and cousins, gently stroked by her mother and aunts. Adults go to work while youngsters are looked after by a caregiver, who gets grief from a pair of boisterous adolescents. This family chronicle takes place not in a suburban living room, but in the depths of the Indian Ocean. The dynamics are played out by sperm whales, filmed over the course of 10 years. Titans of the Sea: A Family Affair is a winner in Jackson Wild’s 2022 Media Awards, which celebrate filmmaking’s unique contributions to science and nature storytelling. And the whales have a lot to tell us.

Gigantic sperm whales are best known as the model species for Moby-Dick, in which novelist Herman Melville portrayed the great white whale as a vindictive force of destruction. Titans of the Sea poses a corrective vision, revealed through close observation of how the whales live their lives. Following more than two dozen whales for a decade—15 females and 11 offspring—the film shows a supremely calibrated social life full of complexity. Nautilus caught up with Guillaume Vincent, the director, to discuss his immersion in the whales’ world.

As a long-time documentary film director, your strong focus has mostly been on terrestrial wildlife. How did you come to be involved with Titans of the Sea?

In 2015 I joined up with Rene Heuzey and Francois Sarano. Rene is a highly experienced underwater cameraman, and Francois is an award-winning marine biologist, a former advisor to Jacques Cousteau. They had been filming a family of sperm whales for years. I came in as producer and director. Getting to observe the whales over this length of time was a revelation.

The footage is mesmerizingly beautiful. There is plenty of drama onscreen, but we are watching at an unusual pace for a film.

Over the years, the whales became acculturated to Rene and Francois, and vice versa! Rene was able to record very intimate interactions. I worked hard to resist cutting the film in a way that distorts the time frame in which things happen. The challenge was to let the film proceed more slowly, more in sync with the whales, while of course moving the story along. It was of the utmost importance that the film stay true, that viewers see what is happening with their own eyes.

There’s a delicate line in the film. One feels immersed in the whales’ world, but the narrator identifies them by human-given names—which of course is anthropomorphic.

To understand what was going on between the whales, it was critical to identify each of them as individuals. So eventually they were given names.

Adult females and offspring live separately from the males for most of the year. The males travel to deeper waters where the food web is that much richer. They return to the group to mate, and then leave again. Adult females also spend a great deal of time diving for food. They go to depths that would crush the smaller animals. The young stay closer to the surface while their mothers hunt. But they are not left alone.

There is no place to hide in the ocean, and the young are highly vulnerable. An adult female who has not given birth basically has the role of nursemaid, and looks after the young. Predators are cued by her presence to keep their distance.

If you admire the wonder of it all, you will want to protect it.

Caretaking by related females has been documented in primates. Anthropologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy called the phenomenon “alloparenting.” That some marine mammals engage in this behavior is a revelation. The film also surfaces new information about how the adult females relate to each other. Well, one might call it “hooking up.”

The whales click to communicate, and different clicks have different meanings. We observed that a particular clicking sequence would be initiated by one female approaching another, who was also clicking. As they approached each other, the sounds would align as if they were completing a round. This signaled what to us was unknown behavior—females caressing each other, stroking each other’s genitals.

I hesitate to call it sexual behavior but it certainly gives that impression! I understand this dimension of social behavior in female sperm whales is new to science.

We showed the film to a big group of researchers, who were fascinated. They wanted to know if there is similar behavior among the males, but we don’t know—we haven’t observed them the same way.

We observe two adolescents, Eliot and White Spot, tease Alfred. To hugely anthropomorphize, Alfred is a sensitive, smaller male. When Eliot and White Spot are confronted by their nursemaid Germane, they resist her. Conflict ensues. It would seem that daily hijinks among the young males revealed deeper social divisions. The family soon breaks into two groups.

Only long observation of the whales could reveal these intricacies.

Helpfully, the narrator tells us that though this makes things hard on the now two smaller groups of whales, it’s good for the species. After Eliot and White Spot were so relentless with Alfred, I was highly surprised to learn their next move.

Yes! Germane, the nursemaid for all the young, stayed with the other group. Which meant there was no female of appropriate age to watch the younger members of the split-off group. Eliot and White Spot had reached an age where they would be expected to leave with the males when the time came. But they did not. They stayed and took over the nursemaid role in their nuclear family.

Since most wild species are under tremendous pressure from human activities, I was surprised that the film does not make an appeal to conservation.

Sperm whales are doing better than they have in 30 years, thanks to protections. At the same time, the ocean remains highly vulnerable from climate change, pollution, and over-fishing. We wanted to keep the focus on the family—on the relationships. If you admire the wonder of it all, you will want to protect it. Curiosity is the first step to philosophy. ![]()

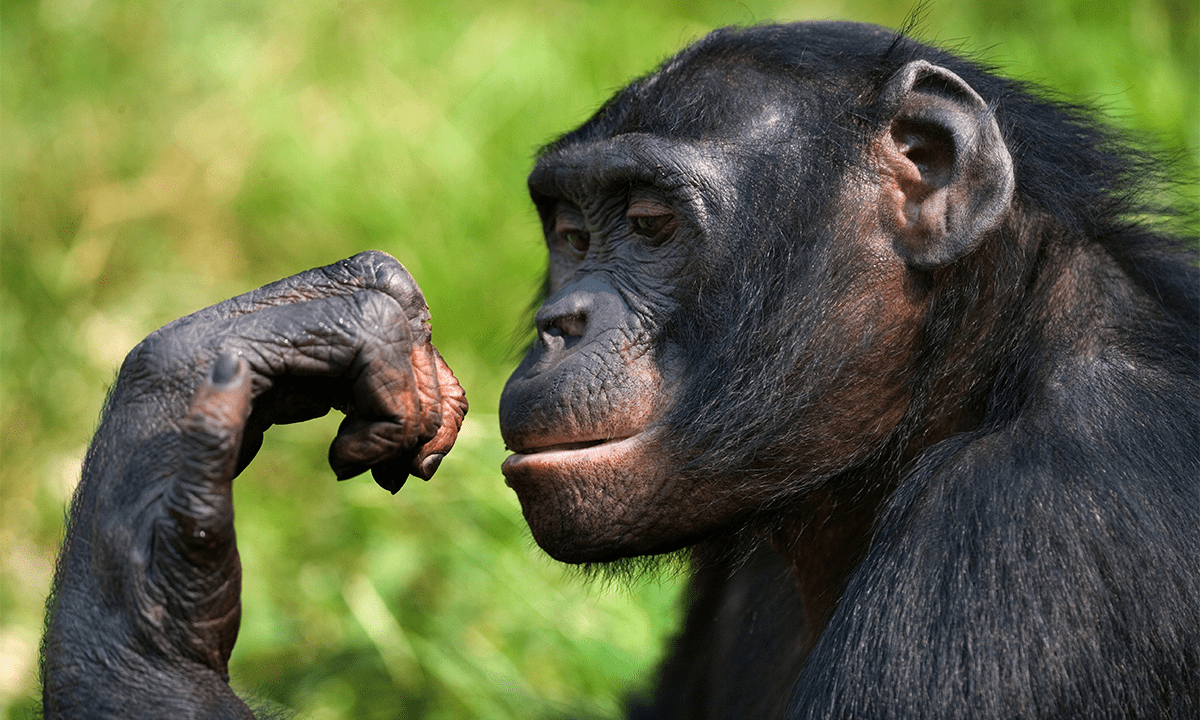

Lead image: Martin Prochazkacz / Shutterstock