The purpose of language is to reveal the contents of our minds, says Julie Sedivy. It’s a simple and profound insight. We are social animals and language is what springs us from our isolated selves and connects us with others.

Sedivy has taught linguistics and psychology at Brown University and the University of Calgary. She specializes in psycholinguistics, the psychology of language, notably the psychological pressures that give birth to language and comprehension.

More recently Sedivy has been writing about language in her own life. She was born in Czechoslovakia, spent time as a kid in Austria and Italy, and came of age in Canada. She speaks Czech, French, and English, and gets by in Spanish, Italian, and German.

In “The Strange Persistence of First Languages,” featured again this week in Nautilus (it first appeared in 2015), Sedivy explores how revisiting her first language, Czech, brought her closer to her late father and revived memories of her own past. In another Nautilus essay, “Why Doesn’t Ancient Fiction Talk About Feelings?” Sedivy burrows into the evolution of literature and how its shift to the interior life of the mind has reflected the expanding complexities of society.

In this interview, from her home in Calgary, Sedivy explains how language enraptures and deceives. Our discussion ranges from evolution to Trump to what makes good fiction and bad writing. Throughout, Sedivy’s insights resonate.

How did language shape human evolution?

That’s entering a very speculative domain, but we can have some insights into that by looking, for example, at populations that exist now that maybe don’t have access to language. For instance, many deaf people around the world are still raised in environments where they’re not really given access to a language because their senses don’t allow them to take in the ambient language around them. Unless they’re put together with other speakers who use a signed modality of language, they might spend most, or even all, of their lives without access to language.

There are some interesting studies that look at what happens when you take someone like this and add the experience of language. There’s a very interesting study by Jennie Pyers and Annie Senghas that looked at Nicaraguan sign language signers as a result of their exposure to language.

Language is the medium with which we communicate with ourselves.

The purpose of language is largely to share the contents of our minds with other people. We often directly refer to contents of minds by using verbs like, “I think,” “he knows,” “she believes,” “she’s pretending.” These kinds of verbs signal something about what’s in other people’s minds.

It turns out that exposure to language, and in particular to language that expresses the idea of peering into other people’s minds, seems to actually hone our ability to read minds, even in non-verbal domains. For example, we become better at deciphering people’s complicated emotions based on their facial expressions.

Aren’t we winging it when we “read” another’s mind?

Yes, and to some extent we’re always winging it because we’re operating from our own senses and our own perspectives; and to a large extent we often have to suppress that information when we try to project ourselves into the mind of another person. There’s this complicated shifting out of your own body and out of your own mind that needs to happen, and that turns out to be sometimes quite difficult.

At the same time, I think we have extremely sophisticated abilities to have some good hypotheses about the contents of people’s minds, even on the basis of very, very indirect information. One way we know this is by looking at the gap between the meaning that’s communicated directly by language and the meaning that we have to infer from what the language gives us. This gap is absolutely pervasive through all of language. We don’t ever go around fully specifying everything that’s in our mind. We take shortcuts because we assume that the person we’re talking to will be able to reconstruct a lot of that.

Here’s a very simple example. If I introduce you to someone as my biological mother, immediately you’re thinking, “Oh. Oh, you have someone who gave birth to you and that person is distinct perhaps from the person who raised you.” I haven’t told you any of that. In fact, most people could truthfully describe their female parent by saying “my biological mother.” But you have added a layer of meaning by virtue of your sensitivity to the fact that most of the time people strip away the details that this is the person who gave birth to you. If I am going to the trouble of giving you that detail, there must be some reason for it, and immediately you start generating hypotheses about the likely reason for that. We do this kind of thing all the time, and much of the time very, very successfully.

How does language help us understand ourselves?

Language is the medium with which we communicate with ourselves, in a sense. It’s the medium that we use to structure our own thoughts, to create our own narratives, to put order into impressions. I imagine just as labeling an object for a baby causes them to pay attention to certain aspects and then to its relationships to other objects, that doing that within ourselves in our own internal monologue might have the effect of creating certain categories within ourselves, allowing us to come to certain conclusions. I think we probably spend more time talking to ourselves than we do to anybody else, and I suspect that a huge amount of shaping our thinking comes from this process.

When does language fail us?

Language fails us in the ways that it’s a very indirect mapping of the world around us. It strips information away, so it’s a great simplifier. You take a very simple concept like an apple and by applying a certain word to it, a symbolic word, we now have turned it into a schema. And that takes away a lot of sensory detail. Sometimes as writers, for example, people really struggle to recreate to put some of that sensory detail back in.

I think the biggest way that language might fail us is in the way that it under-specifies reality. You can see that playing out in communication between people. There are gaps between the meaning that language is able to provide and what it is that we’re trying to jam into language when we try to express ourselves. Some of that meaning gets lost, and on many occasions the person that we’re communicating with isn’t picking up on all of what we’re intending to jam into the language that we use.

Samuel Beckett has called language a veil. Know what he means?

Yes. Yes, absolutely. In a sense, it is a mediator. A very, very simple example of this, is—someone asked me just the other day, “Why is it that words for animal sounds are different in different languages?” Pigs might oink in English, but they make a different sound in another language. The answer to that is we’re basically trying to recreate this auditory stimulus by using the tools that language gives us, which are vowels and consonants. Pigs don’t oink, they don’t make sounds in vowels and consonants—but that’s what language gives us.

We’re trying to take this complex sound and pack it into a string of vowels and consonants, and that’s going to be largely constrained by the particular language we speak, because different languages have different solutions for how they string vowels and consonants together. That’s just a very small example of the veil that language puts between the thing that it’s describing and the way in which it’s described.

Can a powerful person use language to deceive?

Absolutely. I think the tools of language that a deceiver has at his or her disposal are huge. Certainly, directing attention, simplifying … For example, here’s maybe a less obvious way that you can deceive—and this is something I think about a lot as someone who communicates science to a general audience. The notion of simplicity: What happens when you present complex information in simple language? To some extent you have to when you’re dealing with an audience that maybe doesn’t understand the complexity of the issues you’re trying to get across. But if you strip away too much of the complexity, what you’re communicating in part is that the ideas themselves, the issues, are simple.

The biggest way that language might fail us is in the way that it under-specifies reality.

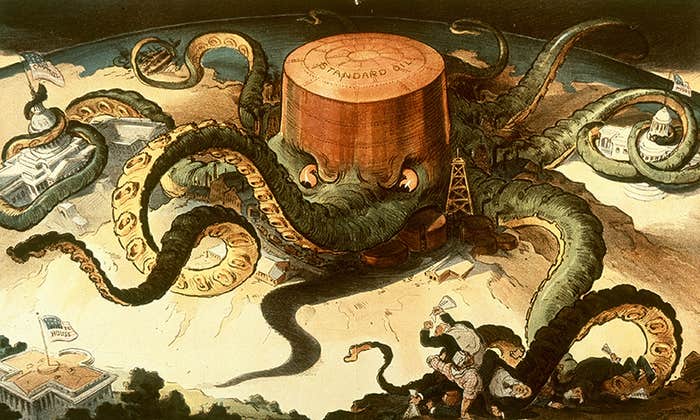

There’s some interesting research that has looked at the correlation between simple language and the tendency of United States presidents to behave in authoritarian ways. There is a predictive relationship that speeches that are expressed using very simple, basic language tend to precede very authoritarian acts, like the use of executive orders, for instance. Simplicity itself is something that can be deceptive. Certainly, for anyone who is in the field of journalism, science, politics, and who has an ethical preoccupation with deception—that just opens up a whole can of worms.

What do you think of Trump’s language?

Well, I think we have rarely had a president who uses such simple and simplifying language. That certainly plays out in the use of the heavy reliance on simple notions like amazing, sad, bad, unfair. These really strip away a lot of the complexities that are behind them. They reduce information into very gross impressions. The simplification of points of view, the simplification of the good and the bad. Even just the conveyance that, “We’re going to make good deals,” for example. “It’s going to be great.” That this is a simple problem just waiting for someone who has the right instincts to come along and solve this, is absolutely pervasive in Donald Trump’s language.

What’s the downside of simplified language?

Well, I think the big downside is that it’s false. The world is a complex place. It’s not a simple environment. There are many forces interacting simultaneously that really elude simple explanations or simple solutions. One thing that I certainly have become very aware of through a couple of decades now of being a scientist is that for every simple, elegant explanation or theory we have come up with, we have discovered that the truth is actually not simple or elegant. It’s messy, noisy, complex.

That’s a problem when we’re trying to communicate it in simple language because we’re essentially lying about the nature of the world. The great challenge is how do we communicate something about the complexity of the world in a way that’s understandable, that’s accessible, but that does its best to limit the amount of lying that we do?

How has studying language shaped your own life?

The biggest effect is that it makes me walk around the social world in utter delight because I’m constantly noticing what’s happening in social interactions or even in a cleverly constructed ad or a beautifully written passage. The training that I have as a linguist and as a psycholinguist allows me to just think, “Ah, I see what’s going on there and why this works.” There’s this resonance of understanding that opens up for me. I think that’s really been the greatest impact.

For every simple, elegant explanation or theory we have come up with, we have discovered that the truth is actually not simple or elegant.

That’s something that I try to impart to my students more than anything, is the idea that you can apply this vast body of knowledge about how language works, the scientific method, and you can start to observe your daily interactions, your conversations, the choices of words that people make or don’t make and the impacts that they have in a much more conscious and aware way. That just makes all of these interactions so much richer and more layered for me.

Have your language studies influenced your appreciation of literature?

Hugely. I have always loved literature. I loved literature before I loved linguistics, before I knew linguistics even existed. I was always just resonating to the things that you could do with language. Again, now there’s a sense of a double vision or a layered awareness that goes on when I read texts and also a sense of better understanding of what might go wrong when things go wrong.

If I hit a clunky phrase, for instance, I often have a sense of, “Oh, well this is why it feels clunky because it’s straining the memory system over here, and if we made a small adjustment we can unravel that and make it much easier to process.” I find that deeply pleasurable just to be able to have that heightened sensitivity to language.

A thing that annoys me is that when I talk to visual artists or photographers, they have some access to scientific knowledge about visual perception that they very easily bring into their work; they don’t find it problematic to discuss combining that with their art. But many writers seem to me to be resistant to the idea of consciously deliberating about language or even learning a whole lot about how it’s put together, how its mechanics work. I have never understood that because it seems to me that you just gain extra tools in having that awareness. Just like we have been talking about how labeling something with a word draws your attention to certain aspects of it. I think having these scientific concepts and tools and vocabulary directs my attention to aspects of language that it might be harder to see if I didn’t have those tools. So this is a great frustration to me that we don’t teach literature, we don’t teach how to write, from the perspective of an understanding of what is it that readers do when they read the text. What kinds of impact is that having on the human mind?

I’m really hoping that will change, but I’m not seeing evidence of it changing very quickly because it’s 30 years ago now that I first took a linguistics course, having no idea what I was stepping into. I think it’s still the case that many students who take a linguistics course now don’t really understand what they’re stepping into until they’re there. That’s a great shame to me.

What makes bad writing?

What makes bad writing? Oh, there are so many ways you can write badly, so, so many ways! I think ultimately bad writing is when you have miscalculated what your reader is doing, whether you’re thinking about that consciously or not.

What do you mean what the readers are doing?

You’re miscalculating how the reader is unpacking meaning from what you have given them in the form of language. If language is just a code, a shorthand to approximate meaning, you know what meaning you have in your mind and you’re using language as the tool, the channel to try to get that across. But that relies on a theory that you have implicitly about how your reader is unpacking that and what resonances psychologically are going off in the mind of your reader as they do that.

One failing you can make as a writer is to not give enough information. The reader gets lost, confused. You have under-specified too much. Another way you can fail your reader is to give too much information. You have underestimated their ability to recover meaning in ways that now irritate them or lead them to look for false meaning.

Fiction allows us to step out of the constraints of reality to project ourselves into possibilities that don’t exist and might exist.

If I introduce you to the only mother I have ever known as my biological mother, I have given you too much information because now you’re searching around for some reason for that redundancy, and you’re coming to a false conclusion, one that doesn’t actually capture the relationship to my mother. Those are just two ways a writer can fail.

They can also fail in, I think, in not understanding or … Writing can fail to one reader and succeed to another, because the set of assumptions a writer has made about what kind of a frame of mind they’re bringing to the reading is correct in the case of one reader but false in the case of another reader. For example, any English teacher, I think, will tell you that when they teach literature to high schoolers there’s a huge range of ability to deal with under-specified meanings or ambiguous meanings or to make inferences on the basis of text. That’s something that I think teachers are now more attuned to, to steering those students who don’t naturally engage in inference-making to try to encourage them to do that, because so much of literature involves making inferences.

Again, I think as a writer you have an implicit idea of the kind of reader you’re writing for and if that misfires for a particular reader, or for all readers, that can be experienced as a failing of the writing.

What good is fiction?

Fiction is assimilation of the world, to a large extent I think. Fiction allows us to step out of the constraints of actual reality to project ourselves into possibilities that don’t exist, might exist, may not yet exist, might have existed in the past. It creates an incredible space to explore hypotheses and that makes it very, very powerful. It allows us to generate, to create in language, worlds that aren’t in front of us. By virtue of having developed these tools to capture worlds that are in front of us we can now take those same tools to create new worlds and to explore the ramifications of those worlds, the what-ifs.

I think that, in a sense, is really analogous to what we’re doing in scientific exploration. When we develop theories about reality, we’re making predictions based on those theories that may or may not map onto actual reality but it allows us a way of generating possibilities, of generating what-ifs, and wondering if we changed this aspect of reality what would be the outcome? That’s really a way of describing an experiment. I think fiction is very analogous to that.

Why is it significant that literature evolved toward inner voices?

I think it’s deeply significant because there’s a lot of discussion nowadays both in the scientific literature and also in the popular press about the importance of social intelligence—the ability to interact with other people in ways that are successful; the ability to read communication that’s implicit; to be flexible in the way that you can communicate with a variety of different people who might bring a variety of different assumptions to play. All of these are correlated with material success, success in relationships—generally, the ability to function in the world.

What’s interesting is there is reason to believe that if you look at people who have a high level of social intelligence, that it doesn’t simply come from genetic luck. Certainly, there are some reasons to believe that people might be genetically predisposed to having a higher or lower level of social intelligence, but it appears that a significant amount of it is conveyed and culturally transmitted. It turns out that there is a very slow process of learning, for instance, how complex emotions work. While even very small children might be able to grasp very simple emotions like happiness, sadness, anger, fear, I have all kinds of complex emotions. Like, think of an emotion like embarrassment. Well, where does embarrassment come from? Embarrassment comes from a theory that you have about how other people are reacting to you and how other people are perceiving you and your own response to that theory that you have. These kinds of complexities of interactions and emotions are something that seem to be quite slowly acquired and that some people hone to a fine degree, other people to a much lesser degree.

Do you think fiction like Virginia Woolf’s has shaped culture?

I do. I think it has pushed culture to be more attentive to the contents, to the intricate, complex contents of each other’s minds, to maybe be more speculative about what other people are thinking and feeling. One of the things that fiction does well, especially modern fiction, is it creates these wildly implausible scenarios and disconnections between events in the external world and the way that people respond to them.

I’m thinking, for example, of a film I saw, Elle, a French movie, where this woman who is the victim of a brutal rape has a really unusual response to it. She begins to seduce her attacker. This is a very unexpected response. If you look at literature dating back many hundreds of years, you wouldn’t see these stories of great disconnections between external events, pushing people into these bizarre responses. That’s something that’s really emblematic of modern fiction and film. What does that do? It immediately makes you think, “Well, why is she doing this? What a strange response. What could be driving that?” and to start generating theories about that.

I think to the extent that fiction has moved into this domain of exploring complex, ambiguous, unexpected responses to events, it seems to really prompt that kind of analysis. I suspect that it’s a very plausible hypothesis that there is a feedback loop that’s going on that the more complicated our societies are, the more dependent they are on these kinds of nuanced interactions and our understanding of them, the more we see that reflected in literature. And in turn, the more we read that literature—or see those films—the more we become exercised or adept at thinking about why people behave the way that they do, what kinds of motives might they be driven by.

Kevin Berger is the editor of Nautilus.

A slightly different version of this interview first appeared in our “Consciousness” issue in April, 2017.