On June 1, 1676 the Battle of Öland was raging, as the Swedish navy grappled with a Danish-Dutch fleet for control of the southern rim of the Baltic Sea. Amid bad weather, Kronan—Sweden’s naval flagship in the region and one of the largest warships of its kind at the time—made a sudden left turn. Its sails began to take too much wind. The ship tipped over as water gushed into its gun ports. Kronan soon lay horizontal on the water. It was then that an explosion rung out, tearing off a large chunk of the vessel’s front side. Kronan’s gunpowder storage room had lit ablaze. The ship—along with around 800 men, loads of military equipment, and piles of valuable coins—sunk to the bottom of the sea, 85 feet down. Sweden lost the battle.

From 1679 to 1686, Swedish divers using diving bells recovered over 60 valuable cannons from the wreck. After that Kronan’s precise location was forgotten, the ship left alone in its watery resting place for almost three centuries. In August 1980, however, a team located the old warship once again. Since then over 30,000 artifacts have been retrieved from the wreck in one of the most elaborate archaeological projects in Sweden’s history. But materials recovered from Kronan also have important implications on Sweden’s future, as well.

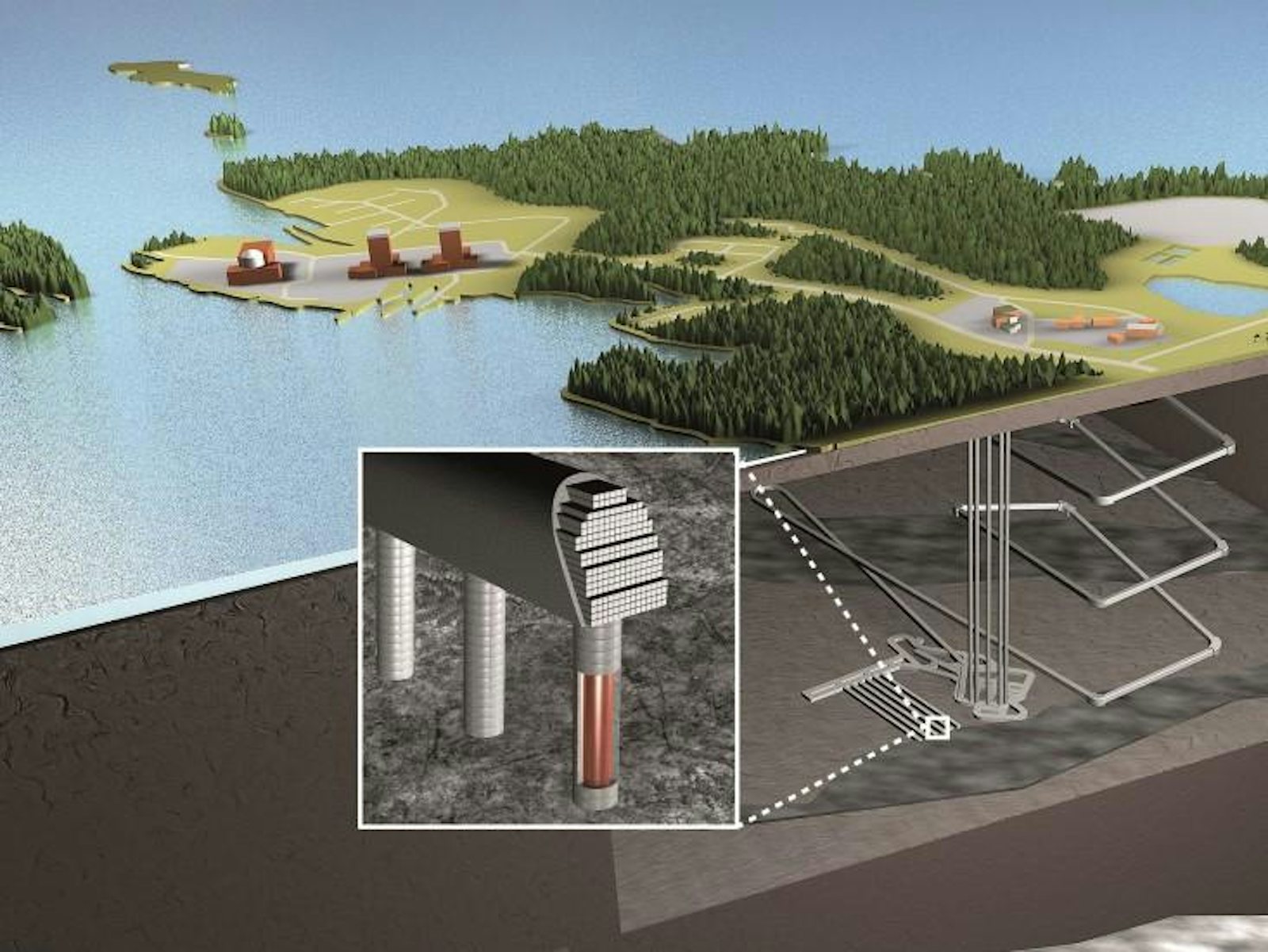

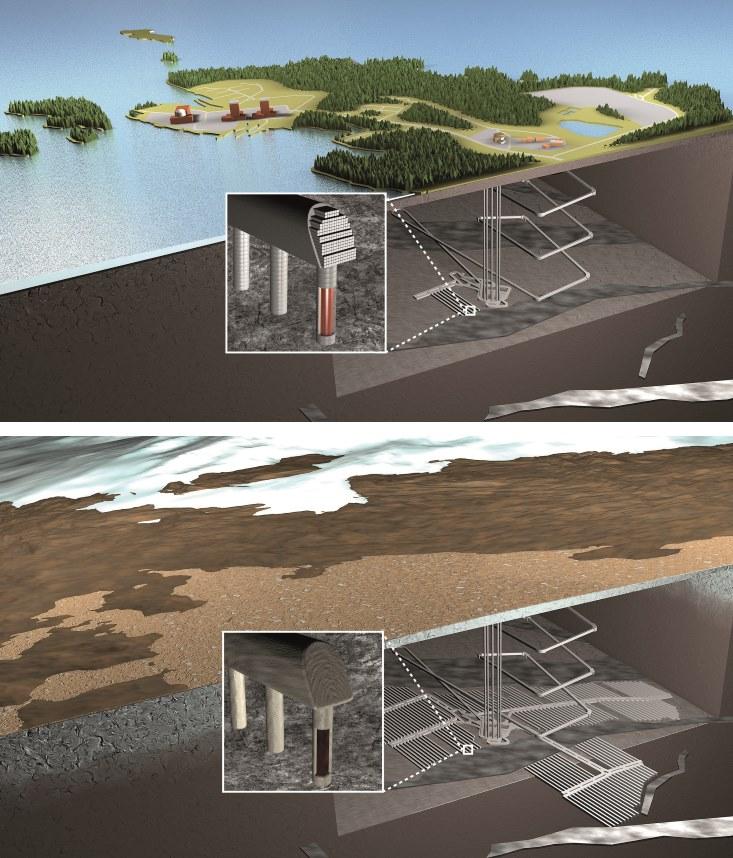

One of the artifacts from the ship—a bronze cannon—has caught the attention of the Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Company (SKB) and Finland’s nuclear-waste-management company Posiva Oy. These companies are working to build what will likely become, in the early 2020s, the world’s first two working, deep-underground repositories for spent nuclear fuel. As part of planning the repositories, SKB experts studied how the cannon fared in a harsh seawater environment over the centuries.

The cannon was selected because it contains a lot of copper, was long partially surrounded by seafloor clay, and sat for ages in in abrasive seawater. Such factors, Posiva experts suggest, makes it a good analog for the nuclear-waste canisters to be used in the repositories, which will be made of copper and surrounded by clay and groundwater for thousands of years. Studying the cannon may help predict how and whether the copper nuclear-waste containers might corrode over the long term. The experts also studied other analogs to help predict how and whether repository components will persevere, break down, or transform in futures near and distant.

The study of these analogs is part of SKB’s and Posiva’s broader endeavors to forecast Nordic regions’ radically long-term futures. In Finland, for instance, experts now work to augur changes in the geological, ecological, and climatic conditions that the repositories’ surrounding region of Olkiluoto might see over the coming millennia. Some of these experts study the possible effects that environmental changes—including those caused by humans and the natural waxing and waning of future ice ages—might have on the long-term durability of the underground facilities. Others assess potential health risks to future humans and other living things that could arise if radionuclides escape from the repository and then, in worst-case scenarios, disperse near or on Earth’s surface.

These farsighted scientific and engineering ambitions were what led me to spend 32 months living in Northern Europe, doing an anthropological study of these experts’ lives and mentalities. The specific band of experts I came to know was developing Posiva’s safety case: an enormous portfolio of technical models, data, and forecasts that aim to gauge the safety of Finland’s planned repository’s over the coming millennia.

As an anthropologist, my interest is in exploring how these experts envision the far future and how that can help us develop a more farsighted view of our world—a skill we must acquire in our current moment of global environmental crisis.

Tomorrow on Facts So Romantic, Vincent Ialenti looks more closely at how researchers used analogs to try to predict the future of the nuclear repositories.

Vincent Ialenti is a U.S. National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow and a PhD Candidate in Cornell University’s department of anthropology. He holds an MSc in law, anthropology & society from the London School of Economics.