As legend has it, a shepherd named Magnes first discovered magnetism. While traversing Mount Ida in what is now northwestern Turkey around 1000 B.C., he noticed that the metal cap of his staff and the nails in his shoes were ineluctably drawn to certain rocks. He dug to uncover the origin of this powerful attraction and discovered the mineral magnetite, a magnetic oxide of iron, suffusing a chunk of lodestone.

Many centuries later, the Chinese invented the first magnetic compass, most likely some time before 100 A.D. But at first, this powerful new technology was primarily used as a divining tool by feng shui practitioners. It was not until the 1200s that magnetic compasses came into regular use for wayfaring, helping intrepid Chinese and European travelers to cross land and sea.

By that time, many scholars understood that the compass needle did not point toward true north, the axis of rotation of the Earth, but rather to the magnetic north pole, which is distinct. The angular difference between true north and magnetic north is called magnetic declination, and its discovery in China and Europe led to a flurry of map making and scientific exploration aimed at explaining both the nature and the source of the Earth’s magnetic pull.

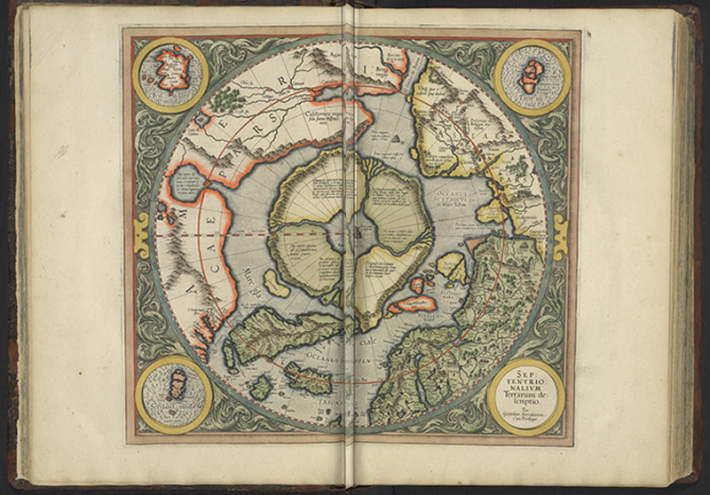

Many early scientists speculated that the north star or certain mountains and rocks must be the sources of polar magnetism. In the first published map of the Arctic and the North Pole, from 1569, Flemish cartographer Gerhard Mercator depicted alluring cliffs and rocks thought to contribute to the polar magnetic field. An enlarged second edition (below) shows at its center an inky gnarled island labeled “Rupus Nigra et Altissima,” which translates to “very high black cliff.” Mercator later described this island in a letter to English mathematician John Dee as measuring 33 miles across and consisting “all of magnetic stone.”

One of the very first maps of magnetic declination was published more than a century later, in 1701, by Edmond Halley, an English mathematician, physicist, and astronomer. Halley produced the map after traveling around the Atlantic aboard a sloop of war named the Paramour on an expedition sponsored by King William III. His map was the first to use isolines to indicate how the Earth’s magnetic field wrapped in curves around the planet’s surface. Later expeditions set out to map not only magnetic declination but also the shifting magnetic poles, which scientists had discovered change position over time.

In 1831, James Clark Ross led a party that identified magnetic north on a peninsula they dubbed Boothia Felix, now a Canadian territory of Nunavut. (The expedition was funded by Ross’ uncle Felix Booth, a wealthy British gin distiller.) That pole is shown in the 1856 Chart of Magnetic Curves of Equal Variation by Peter Barlow. The South Magnetic Pole was not mapped until 1909 in an expedition led by British explorer Ernest Shackelton. These poles both currently lie at sea.

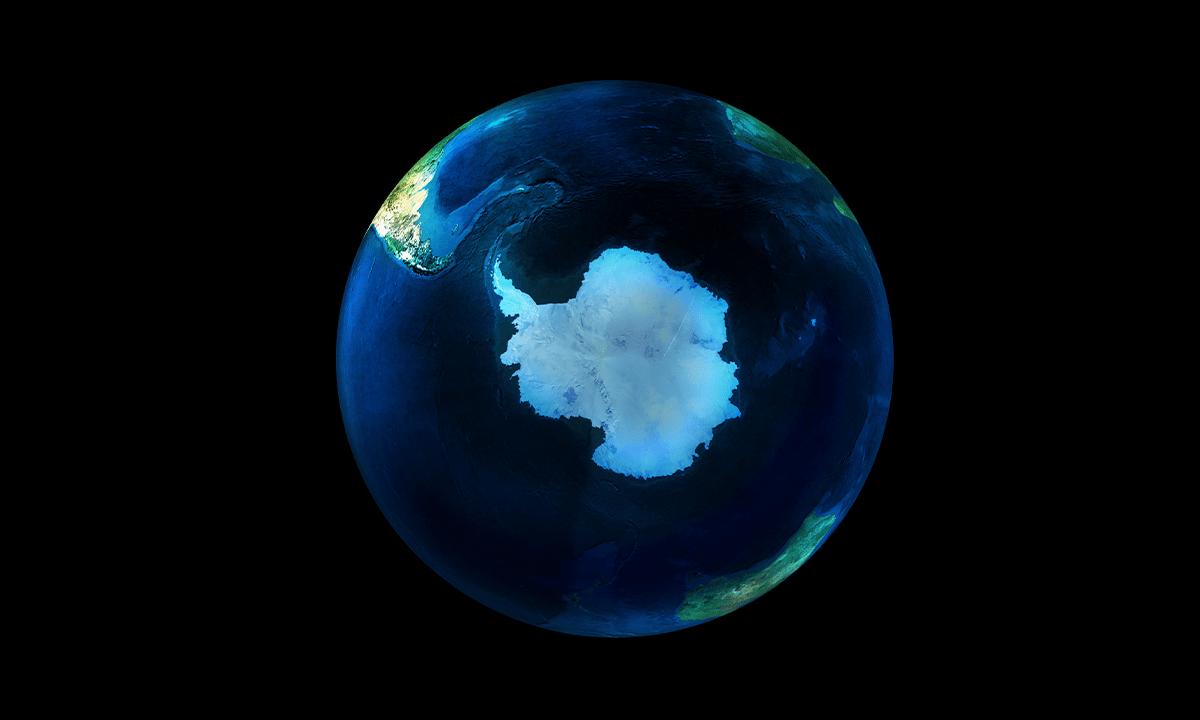

Today we understand that the Earth’s magnetic field is generated by the flux of molten iron in its core, which creates an electrical current that flows around the equator in an imperfect loop. But much about how this field works and shifts over time remains a mystery to be divined and mapped by future explorers. ![]()

Lead image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division.