When it comes to recovering from insult, the adult human brain has very little ability to compensate for nerve-cell loss. Biomedical researchers and clinicians are therefore exploring the possibility of using transplanted nerve cells to replace neurons that have been irreparably damaged as a result of trauma or disease. However, it is not clear whether transplanted neurons can be integrated sufficiently, to result in restored function of the lesioned network. Now researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Neurobiology in Martinsried, the Ludwig Maximilians University Munich, and the Helmholtz Zentrum München have demonstrated that, in mice, transplanted embryonic nerve cells can indeed be incorporated into an existing network and correctly carry out the tasks of damaged cells originally found in that region.

Neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease, but also stroke or certain injuries lead to a loss of brain cells. The mammalian brain can replace these cells only in very limited areas, making the loss in most cases a permanent one. The transplantation of young nerve cells into an affected network of patients, for example with Parkinson’s disease, allow for the possibility of a medical improvement of clinical symptoms. However, if the nerve cells transplanted in such studies help to overcome existing network gaps or whether they actually replace the lost cells, remained unknown.

In the joint study, researchers of the Max Planck Institute of Neurobiology, the Ludwig Maximilians University Munich, and the Helmholtz Zentrum München have specifically asked whether transplanted embryonic nerve cells can functionally integrate into the visual cortex of adult mice. The study was supported by the center grant (SFB) 870 of the German Research Foundation (DFG). “This brain region is ideal for such experiments,” says Magdalena Götz, joint leader of the study together with Mark Hübener, who continues to explain: “By now, we know so much about the functions of the nerve cells in the visual cortex and the connections between them that we can readily assess whether the new nerve cells actually perform the tasks normally carried out by the network.”

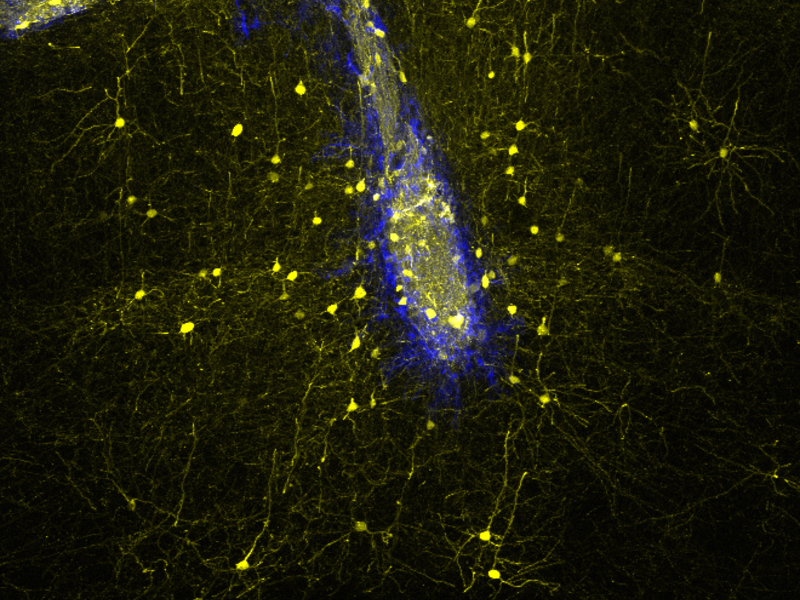

In their experiments, the team transplanted embryonic nerve cells from the cerebral cortex into lesioned areas of the visual cortex of adult mice. Over the course of the following weeks and months, they monitored the behavior of the implanted, immature neurons by means of two-photon microscopy to ascertain whether they differentiated into so-called pyramidal cells, a cell type normally found in the area of interest. “The very fact that the cells survived and continued to develop was already very encouraging,” Hübener remarks. Together with Tobias Bonhoeffer, he is set to unravel the structure and function of the mouse visual cortex. But things got really exciting when the scientists took a closer look at the electrical signals of the transplanted cells. In their joint study, Ph.D. student Susanne Falkner and post-doc Sofia Grade were able to show that the new cells formed the synaptic connections that neurons in their position in the network would normally make, and that they responded to visual stimuli.

The team then went on to characterize, for the first time, the precise pattern of connections made by the transplanted neurons. Astonishingly, they found that pyramidal cells derived from the transplanted immature neurons formed functional connections with the appropriate nerve cells all over the brain. In other words, they received precisely the same inputs as their predecessors in the network. In addition, the cells were able to process that information and pass it on to the correct downstream neurons. “These findings demonstrate that the implanted nerve cells have integrated with high precision into a neuronal network into which, under normal conditions, new nerve cells would never have been incorporated,” explains Götz, whose work at the Helmholtz Zentrum and at the LMU focuses on finding ways to replace lost neurons in the central nervous system. The new study reveals that the adult mammalian brain is able to retain its ability to regenerate with the aid of transplanted, immature neurons, which are capable of closing functional gaps in an existing neural network.

Lead image: Neuronal transplants (blue) connect with host neurons (yellow) in the adult mouse brain in a highly specific manner, rebuilding neural networks lost upon injury. Credit: © Sofia Grade (LMU/Helmholtz Zentrum München)

This article was originally published by Max Planck Neuroscience on Oct. 26, 2016. The relevant study can be retrieved here.

Read more at Max Planck Neuro.