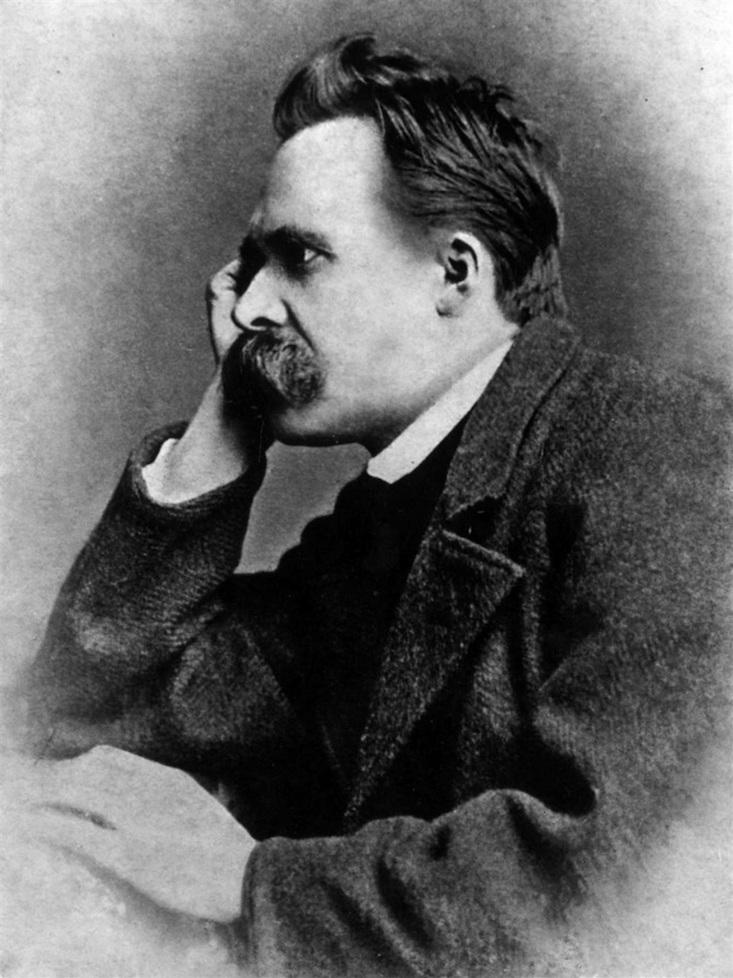

Since his death in 1900, the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche has had the unfortunate distinction of being blamed for three catastrophes to have befallen Western civilization. He was blamed for the First World War, when his inflammatory and bellicose writing became cult reading not only for Europe’s restless youth, yearning for blood sacrifice at the beginning of the 20th century, but also for a German military class adjudged to have initiated that catastrophe.

As if being charged for one world war wasn’t bad enough, Nietzsche was also blamed for the Second World War, with his talk of superior “Supermen” [Übermenschen] crushing the “decadent” and “weak” selectively appropriated by Hitler and the Nazis. This was despite the fact that Nietzsche loathed German nationalism and especially despised anti-Semites for their pathetic resentment.

And thirdly, in the past 50 years, Nietzsche has been blamed for a more silent disaster: the rise of relativism and the idea that there is no such thing as objective truth. Seldom now, especially in academia, do you now read the word “truth” written without those doubting—and even contemptuous—inverted commas. One of the most resilient doctrines of our times is that all knowledge depends on who is saying it and for what motive. This relativism is invariably traced back to Nietzsche.

This is largely to do with French philosopher Michel Foucault’s rehabilitation of Nietzsche. Foucault’s writing on power and knowledge in the 1960s and 1970s, which has been widely disseminated in society ever since, drew upon quotes from Nietzsche that “truth” stems from the desire for power and has no eternal objective foundation. In his landmark lectures, “Truth and Juridical Forms,” delivered in 1973, Foucault said of the myth of “pure truth”: “This great myth needs to be dispelled. It is this myth which Nietzsche began to demolish by showing… that behind all knowledge [savoir], behind all attainment of knowledge [connaissance], what is involved is a struggle for power. Political power is not absent from knowledge, it is woven together with it.”

I believe that it’s time that the great man and free-thinker par excellence was reclaimed by the school of the Enlightenment.

When you hear cries on campus or in academic literature these days that knowledge, truth or science are but “white” or “male” inventions, look no further than Foucault to discover from where this rhetoric came. And because Foucault is open in his debt to Nietzsche, he helped to raise Nietzsche to his current status as the godfather of postmodernist relativism.

He has consequently been maligned as the source of our nihilist discontents. In Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind (1987), a key work in the Culture Wars, Bloom complained that Nietzsche was behind the emergent spirit of nihilism in academia, the fount of the corrosive culture of relativism eating away at the values of liberal democracy. “Nobody really believes in anything anymore,” wrote Bloom, “and everyone spends his life in frenzied work and frenzied play so as not to face the fact, not to look into the abyss. Nietzsche’s call to revolt against liberal democracy is more powerful and more radical than is Marx’s.”

Elsewhere, in Experiments Against Reality (2000), conservative commentator Roger Kimball damns “Nietzscheanism for the masses, as squads of cozy nihilists parrot his ideas and attitudes. Nietzsche’s contention that truth is merely ‘a moveable host of metaphors, metonymies and anthropomorphisms,’ for example, has become a veritable mantra in comparative literature departments across the country.” More recently, Peter Watson opened his 2014 work The Age of Nothing with the following questions on the book’s very first page: “Is there something missing in our lives? Is Nietzsche to blame?”

But is Nietzsche really to blame? And was he really a relativist? I would say that he isn’t and he wasn’t. I believe that it’s time that the great man and free-thinker par excellence was reclaimed by the school of the Enlightenment.

Nietzsche is often invoked favorably by relativists, or denounced by their detractors, for an infamous statement near the beginning of his 1878 work, Human, All Too Human. It reads: “There are no eternal facts, nor are there any absolute truths.” Yet elsewhere in the same book he exhorts the values of “rigorous reflection, compression, coldness, plainness… restraint of feeling and taciturnity.” Thus spoke the real, authentic language of Nietzsche’s rational, harsh, and demanding philosophy—not the lazy relativism of legend and hearsay. And the most interesting and telling thing about Human, All Too Human is that it is actually dedicated by the author to Voltaire, one of the principal propagators of the Enlightenment.

This shouldn’t surprise us. Nietzsche, after all, attacked superstition, religious dogma, and uncritical, unexamined, and outdated ways of thinking—just as Voltaire did. They both believed that Christianity’s god was dead. And they believed in thinking for yourself and daring to challenge the consensus. As Nietzsche later reflected: “Voltaire is, in contrast to all who have written after him, above all a grand seigneur of the spirit: precisely what I am, too.” When writing Ecce Homo in the late 1880s, Nietzsche sought to resurrect the Voltairean spirit in Europe, which he felt by his times had been washed away by pessimistic Romanticism. “Voltaire still comprehended umanità in the Renaissance,” Nietzsche wrote, “the cause of taste, of science, of the arts, of progress itself and civilization.”

In Human, All Too Human, Nietzsche in turn denounces Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the writer many claim birthed Romanticism. “It’s not Voltaire’s temperate nature, inclined to organising, cleansing and restructuring, but rather Rousseau’s passionate idiocies and half-truths that have called awake the optimistic spirit of revolution, counter to which I shout: ‘Ecrasez l’infame!’ [“crush the infamous thing!”— referencing Voltaire’s cry against superstition]. Because of him, the spirit of the Enlightenment and of progressive development has been scared off for a long time to come: let us see (each one for himself) whether it is not possible to call it back again!”

Truths were to be obtained and striven for, but they were always to be tentatively held, ready to be jettisoned when they were disproved or no longer useful.

Nietzsche believed in truth, albeit of an unstable, contingent, perspectival, and disposable variety. He believed in constant experimentation and argument. His Übermensch forever goes beyond and above. This is why they had to struggle, because truth was difficult but ultimately necessary to obtain through free-thinking and reason. As he wrote in Daybreak (1881): “Every smallest step in the field of free thinking, and of the personally formed life, has ever been fought for at a cost of spiritual and physical tortures… change has required its innumerable martyrs… Nothing has been bought more dearly than that little bit of human reason and sense of freedom that is now the basis of our pride.” Far from being casual about truth, Nietzsche cared deeply about it. And any truth we held had to earn its keep. “Truth has had to be fought for every step of the way, almost everything else dear to our hearts, on which our love and our trust in life depend, had to be sacrificed to it,” he wrote later in 1888 in The Antichrist.

Nietzsche believed truths had to be earnt. He believed we had to cross swords in the struggle for truth, because it mattered so dearly, not because “anything goes.” We had to accept as true even that which we found intolerable and unacceptable, when the evidence proved it so. All points of view certainly are not valid. Walter Kaufmann, who began the mainstream rehabilitation of Nietzsche after the Second World War, concluded in the fourth edition of his classic Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist (1974): “Nietzsche’s valuation of suffering and cruelty was not the consequence of any gory irrationality, but a corollary of his high esteem of rationality. The powerful man is the rational man who subjects even his most cherished faith to the severe scrutiny of reason and is prepared to give up his beliefs if they cannot stand this stern test. He abandons what he loves most, if rationality requires it. He does not yield to his inclinations and impulses.”

Of course our truths aren’t eternal. Times change. While Nietzsche’s quote that “there are no eternal facts” has been appropriated by relativists, this statement is entirely consistent with our Popperian approach to truth today: We hold on to truths before new evidence comes along to prove otherwise. Copernicus had fathomed the truth until Galileo came along with a better one. Newton’s physics were right until Einstein supplanted them. The science of tomorrow will inevitably disprove the science of today.

Nietzsche was in the end a radical empiricist—a self-declared enemy of ideology, ideologues and people who cling dogmatically to systems, beliefs and “-isms.”

Truths were to be obtained and striven for, but they were always to be tentatively held, ready to be jettisoned when they were disproved or no longer useful. Nietzsche wrote how contingent truths were useful for our everyday lives: “One should not understand this compulsion to construct concepts, species, forms, purposes, laws… as if they enable us to fix the real world; but as a compulsion to arrange a world for ourselves in which our existence is made possible. We thereby create a world which is calculable, simplified, comprehensible, etc, for us.” Not all points of view were equally valid, because some were useful, and others were useless.

Nietzsche was in the end a radical empiricist—a self-declared enemy of ideology, ideologues, and people who cling dogmatically to systems, beliefs, and “-isms.” He deplored Kantian metaphysics for the same reason he decried Rousseau’s Romanticism: Both were detached from the here and the now of real life. Both told us nothing about what was important or useful.

Truths do change with the times. Our truths are not eternal and do indeed evolve, and not all truths are “equally valid.” They have to prove their worth. Nietzsche put it so in a youthful letter to his sister, “If you wish to be a devotee of truth, then inquire.” What champion of the Enlightenment would argue with that?

Patrick West is a columnist for spiked, where this post originally appeared. It is reprinted with permission. West’s new book, Get Over Yourself: Nietzsche For Our Times, will be published on August 1 by Imprint Academic. Preorder it here. Follow him on Twitter: @patrickxwest.

WATCH: David Krakauer, the president of the Santa Fe Institute, says literature is ontological experimentation.