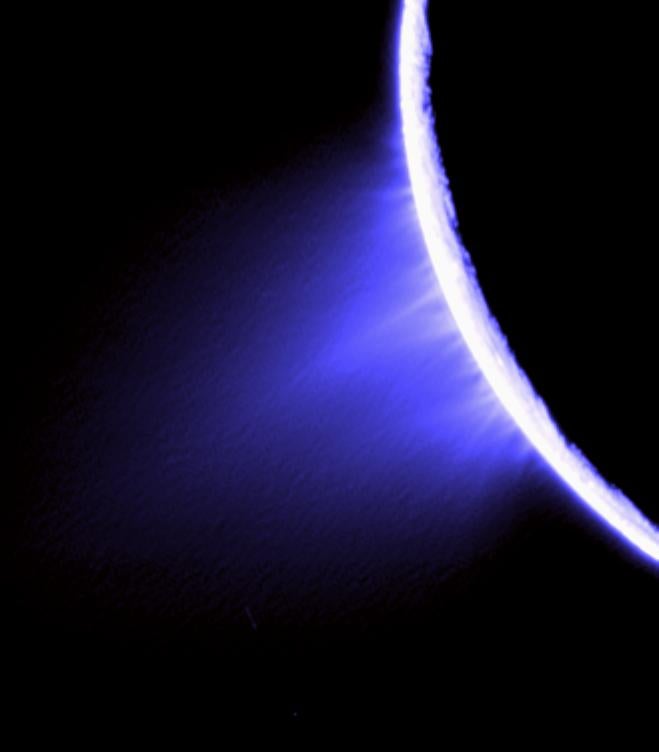

Many moons of the outer solar system have vast underground oceans that scientists now think are the best places to look for life in the solar system. But only one of those moons has an ocean that we can study today, without having to develop and send a complicated drilling apparatus. On Enceladus, the ocean comes to you. It flares through the south polar region in roughly 100 geysers. The Cassini spacecraft, flying through the plume created by these geysers to collect samples for analysis, has discovered that the ocean consists of salt water, laced with organic compounds and evidence of hydrothermal activity on the moon’s sea floor, suggesting it is mixing with a core of rock. A future mission could perform the same trick and sample the plume for organisms.

The leading advocate of studying Enceladus is planetary scientist Carolyn Porco, who splits her time between the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco and the University of California at Berkeley, while still manning the helm of the Cassini Imaging experiment headquartered at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado. Porco has taken part in the Voyager and Cassini missions and is now part of a proposal to conduct a mission that would go back to Enceladus in search of life. Nautilus spoke to her to learn why she’s so excited about Enceladus and what comes next for planetary science. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

What’s so special about Enceladus?

I did my thesis on Saturn’s rings and my postdoctoral work on the rings of Uranus and Neptune. When Cassini began, I was chosen to lead the imaging team. So I was going back to Saturn, only now I had a much wider outlook—rings, atmospheres of Saturn and Titan, and all the icy satellites, big and small. I still pursued, when I could, my own research on rings and produced some really good results that I’m very proud of.

But once we found the geysering activity at the south pole of Enceladus, I was hooked. This was the best place to search for extraterrestrial life and I wanted to be part of that. It was irresistible. I’m still involved in trying to determine the physical characteristics of the geysers erupting from Enceladus and the plume they form and what all that means for future missions that will collect material from the plume and search for evidence of life. Right now, nothing that one can do in planetary science is, to me, more exciting than that.

I’ve heard more about the potential for life on Europa than Enceladus. Why do you believe Enceladus is a better bet?

People have been talking about Europa for decades, and a mission back to it had tremendous momentum behind it before Enceladus came along. Enceladus was the newcomer on the block so, in some sense, we had to wait our turn. I didn’t think, and I still don’t think, Europa was the correct choice if the goal was to find evidence for life as quickly as we could. There is no other extraterrestrial habitable zone in the solar system that we understand environmentally as well as we do the subsurface ocean of Enceladus and its expression as a giant plume, fed by more than a hundred geysers. No place else checks all the boxes. So all other things being equal, we’re in a much better position to return the goods with Enceladus.

How do you approach taking the data you get from missions—measurements and photographs—and turning them into theories of an underground ocean?

A moon in Enceladus’s position with an interior ocean under its ice shell will have a slightly different rotation rate than one that is solid throughout. So, you measure the moon’s rotational motion, as determined by how the positions of particular features on the surface change over the course of the moon’s orbit, and compare these measurements with calculations based on the two options. That was painstaking work for my team members (at Cornell University) who were responsible for the discovery, but it yielded gold.

If we did find life on Enceladus, what do you think it would look like?

Ha! There’s no real telling. We aren’t getting our hopes up too high. Microbes would be tremendous. I’ve been imagining single-celled microorganisms but who knows? Maybe it’s already evolved to multi-cellular life. To hope for lobster and sushi is probably getting too hopeful!

Besides Enceladus, what do you believe should be our next big goal in space exploration?

In solar system exploration, it should be getting an orbiter to Neptune and its moon Triton so we can understand, as intimately as we do Saturn and its environs, what a so-called ice giant like Neptune is like. It’s a very different class of gaseous planet than Jupiter or Saturn, and it is woefully understudied.

Seeing our small, fragile planet is a tremendously moving and exalting sight.

But an even more pressing need is to study and understand Earth and its biosphere, and the stress those systems are currently undergoing because of our activities. We are in crisis right now, and we may just be seeing the beginnings of our own demise. To cut funding of Earth science, as is planned by the Trump transition team, should be regarded as a crime against the Earth, humanity included.

You’ve played a key role in the creation of photographs like the Pale Blue Dot. How did that image become so iconic, and how do you recognize a photo that will resonate with people?

I am proud to say that I came up with the idea independently of Carl Sagan, as did one or two others on the Voyager project, but it was Carl who led the effort once it was given the green light. It became iconic because of what Carl had to say about the image, and the way that he romanced it and turned it into an allegory on the human condition, so that even the title “Pale Blue Dot” has come to signify a call to planetary brotherhood and protection of the environment. And it’s become clear that seeing our small, fragile planet as it would be seen by others in the skies of other worlds is a tremendously moving and exalting sight. It’s instant recognition of who we are, where we are, and how we fit into the cosmic picture.

When I came up with the idea for “The Day the Earth Smiled,” a Cassini image of the Earth and Saturn together, I suspected that it would be a big hit. It was a way to make that moving sight of our beautiful blue-ocean planet even more moving to everyone, a way for people around the globe to feel engaged in a deeply personal way with our solar system, our planet and each other. Judging from the responses we received, it worked!

I hear you’re a big Beatles fan. If you had to choose, whom would you take to dinner: John, Paul, George, or Ringo, and why?

Ha! Well, probably John and George. I think I’d have the most to say to those two; they were the deepest intellectually. But I think if that had ever come to be, I would have passed out at the dinner table from shock, head in my soup. So best that it never happened!

Two weeks ago, Cassini began swooping close to the Saturn’s rings, preparing for its final dive next year into the planet’s atmosphere. How are you feeling about the mission, now that it’s in its last stages?

I have mixed feelings these days. On one hand, I’m anxious for it to be over. It’s been a great deal of work and concentration on one set of goals: getting the best science from our cameras and informing the public in the most inspirational and clearest manner possible of our findings. It has been the best job in the inner solar system, but even good things sometimes need to come to an end, and it’s time. On the other hand, it will be a big, abrupt juncture when it’s finally finished, so there is a strong element of sentimentality to these final days.

It’s becoming clear to me that I’ll probably enjoy the mission even more in memory, when, instead of working breathlessly to make things happen, I’m relaxing in a rocking chair looking at that gleaming point of light in the night sky that I know is Saturn, and thinking about all the tremendous things we’ve come intimately to know there. I’ve had some exceedingly difficult times on this project and issues I had to contend with that I’d rather not remember, but also a great many fond moments, and moments of bursting pride and joy. I will walk away from it all grateful. Not everyone gets to do what I’ve spent the last 26 years doing.

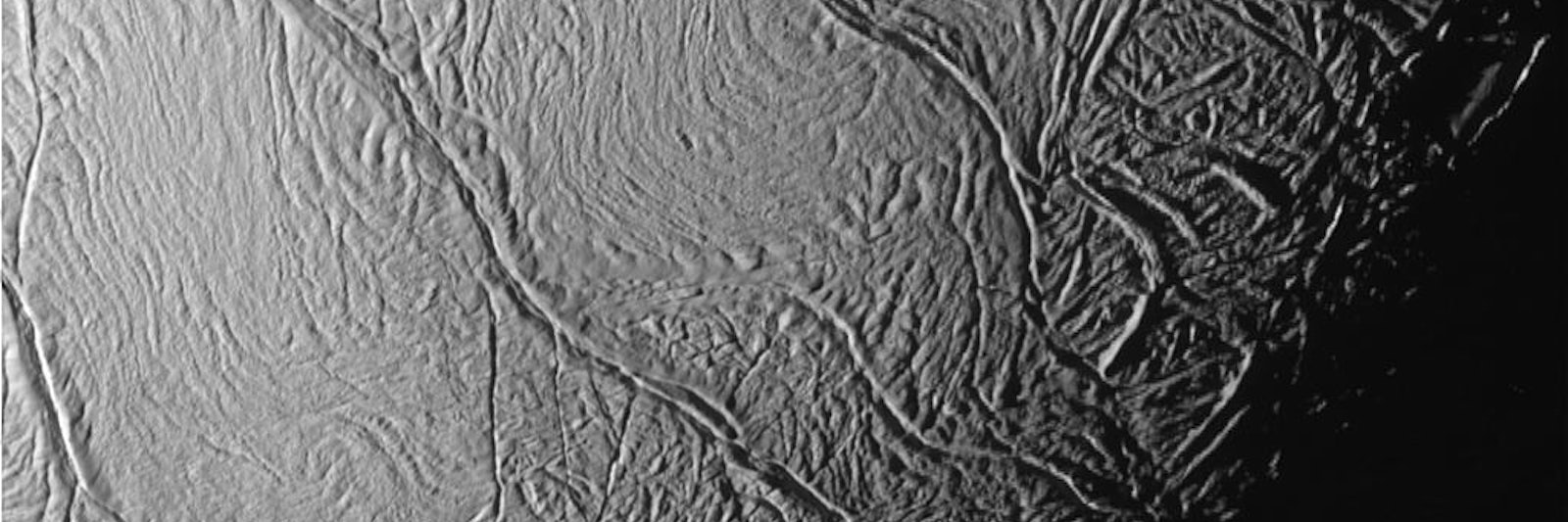

Lead image: Fractures known as “tiger stripes” in the south polar regions of Enceladus, as imaged by the Cassini spacecraft on July 14, 2005. Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute