For longer than recorded history, gemstones have been used to tell stories. Passed down through generations, they carry the legends of our ancestral past. They also carry with them a much, much older history: the geological echoes of our planet’s very formation. As shifts deep within the Earth’s core drove its tectonic plates, compression, heat, and chemical reactions created a new set of minerals, beautiful to the human eye. Understanding that these were objects of record, of permanence, humans wove their own, new stories around them, making meaning from mystery.

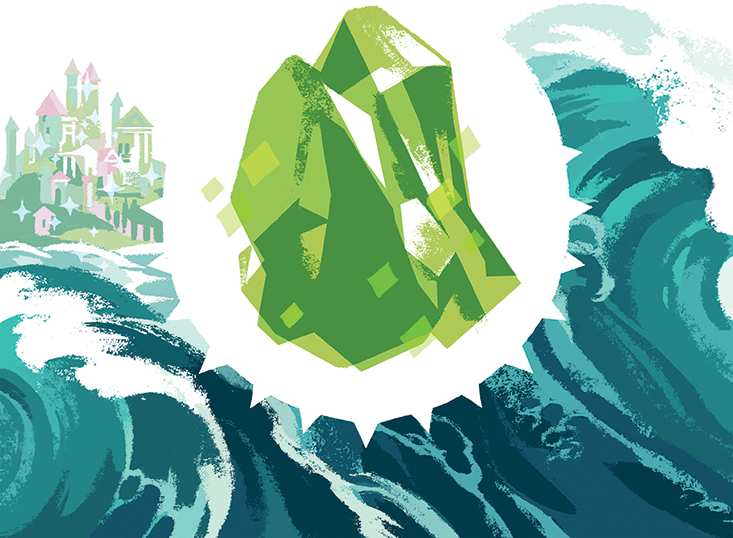

Peridot of the splitting sea

The island of Zabargad in the Red Sea has been home to the world’s finest specimens of peridot for as long as 3,500 years, since its mines were first worked for Egyptian Pharaohs. The island was created roughly 30 million years ago, during the original parting of the Red Sea, when the Earth’s crust separated, folding up mountains and opening an expanse of salt water.

During this shift, small crystals of olivine, a mineral found in the Earth’s mantle, formed peridot. As seawater rushed through fractures in the ocean floor, peridot was thrust through the mantle’s layers and redeposited at the surface. Serpentine veins of peridot still run along Zabargad’s east-west fault zone under the Mediterranean sun. The story of its deep origins found its way into the final book of the Bible, Revelations, in which John the Divine is in exile on the Greek island of Patmos. According to the story, it is there that God speaks to him, telling him the world will be reforged, that the sea will drain away and leave land. On that land will be a new Jerusalem and the foundation of the city will be made of precious stone. One of those stones will be peridot.

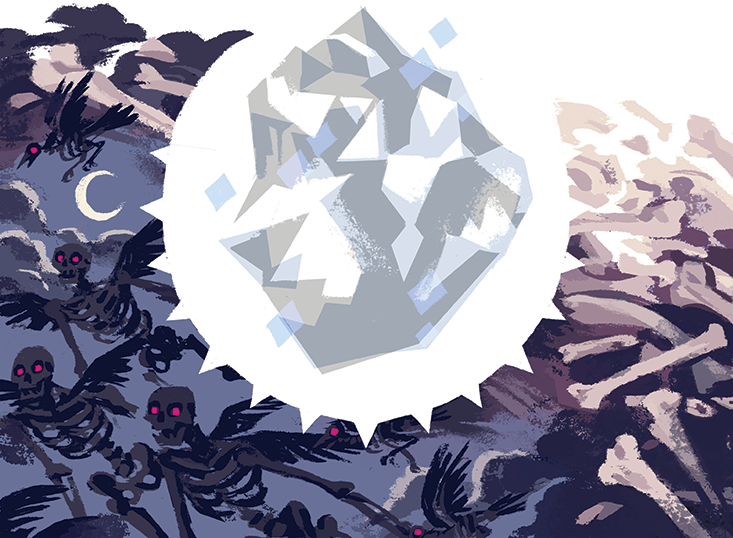

Diamond of the Earth’s core

Diamonds are born deep in the Earth, from the oldest pieces of continental crust—ancient relics of the planet’s formation. Their translucent bodies hold stories that date back billions of years. Imperfections trapped within the diamonds bear the signatures of the crust below ancient oceans, and of ancient life—dead matter forced back into continental crust, some 100 miles below where living creatures took their last breaths. Under tremendous pressures and temperatures, these elements were forged into an indestructible stone that would live for 3.5 billion years, holding tales of a prehistoric past. Even now, the true process of diamond formation remains a mystery. What is known is that diamonds were created from limestone that was stripped of its oxygen atoms, leaving only pure carbon. They were brought to Earth’s surface on a magma called kimberlite, as it was forced through the chimneys of volcanoes in one giant heave. Over time, the diamonds drifted into rivers and valleys. In the Middle Ages, fables said that diamonds came from “the land where it is six months day and six months night.” They were guarded by venomous creatures who wounded themselves on the stones’ sharp crystalline points, saturating them with venom. Whether because of that story or despite it, diamonds were said to have medicinal qualities—namely as an antidote for poisons.

Jade of the dying oceans

There was once a great ocean that flowed westward between the ancient supercontinents of Gondwana and Eurasia; (the former later split into South America, Africa, Arabia, Madagascar, India, Australia, and Antarctica.) Then, 50 million years ago, Gondwana and Eurasia collided. The impact heaved up the Alps, the Himalayas, the Pyrenees, and the Atlas mountains. The ancient ocean floor was thrust northward onto the edge of the Eurasian continent. As the ocean waters were compressed by the titanic pressures of slabs of earth, trace elements of sodium, aluminum, silicon, and oxygen coalesced into the jadeite (or jade). These vestiges of a dying ocean were then buried in the world’s tallest mountain peaks. Hints of this cataclysm appear in early Chinese folk religion, which says that the universe came into existence from the union of matter and movement. Then, the greatest of all deities, Jade Emperor, Yu-huang Shang-Ti (yu means jade), fashioned mankind from clay, tenderly sculpting humanity in his palms. He laid the first humans out to dry and harden in the sun. As they were drying, a great rain came and droplets speckled early man, causing all the world’s illnesses. In later Chinese culture, jade is believed to be the embodiment of the Confucian virtues of courage, wisdom, modesty, justice, and compassion.

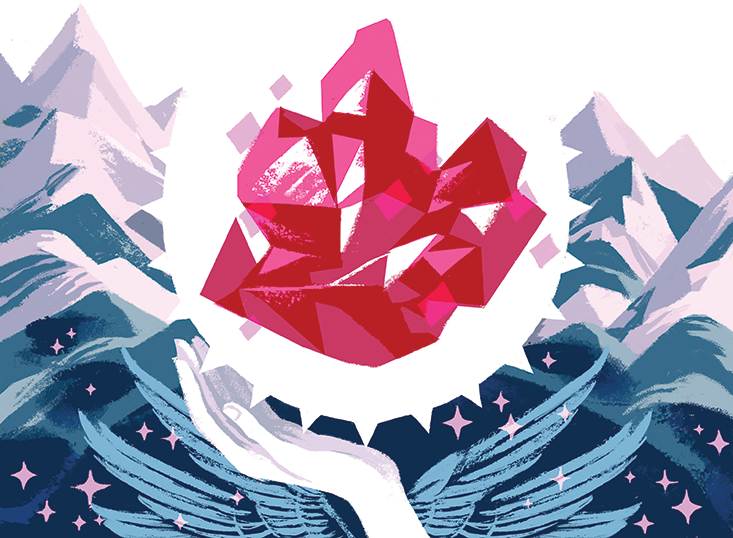

Ruby of the new mountains

The world’s most prized rubies were formed 50 million years ago in marble deposits when India, which at the time was a standalone continent, moved northward and crushed up against the Eurasian continent. The collision created the Himalayas, leaving ruby deposits in Afghanistan, Kashmir, Pakistan, Nepal, Myanmar, and Vietnam. Shale stones, which are formed from sediment washing off land, were forged into crystals of aluminum and oxygen by the high pressure and heat present under the Earth’s crust. As the two continents collided, some crystals were forced upward out of their fetal furnace towards the surface. As they rose, the crystals crashed against layers of fossilized life, and their aluminum atoms—remnants of the ancient clay riverbeds—were forced out by atoms of chromium—remains of organic matter in fossilized carcasses. The result was a crystal so red that early Burmese miners called it “pigeon blood.” In Islamic folklore, Allah created an angel to hold the Earth in place on his shoulders. The angel grasped the Earth and held it above his head, but there was no support for his feet. So Allah created a mountain of ruby in which were 7,000 holes, a sea pouring from each.

Emerald of the ancient coasts

Emeralds are forged in small chambers of magma that form in the violence of land meeting sea, when oceanic crust slides under continental crust and mountain peaks flare up from their bond. As magma travels to the earth’s surface, it bubbles, much like a bottle of carbonated water erupts with the twist of a cap. Trapped inside the pockets of magma are tiny particles of beryllium, which give emerald its color. Chromium enters the mix through remains of organic matter buried in coastlines. When beryllium-rich magma comes in contact with the chromium-filled coastline rocks, emeralds are born. An ancient Colombian legend describes its own fusion myth for emeralds. The god Ares created the first man and woman and promised them eternal youth if they remained faithful to one another. But because the woman, Fura, did not remain faithful, she and her husband, Tena, began to age. Ares took pity on the now-mortal couple and turned them into two towering crags that would stand high above the valley of the Minero River. In the depths of the crags, Fura’s tears would rest for eternity in the form of emeralds. Today, the two crags stand as the official guardians of Colombia’s emerald mines zone.

Adrienne Berard’s writing has appeared in Narratively, The Real Deal, The Star Tribune, The Columbus Dispatch, and other publications. Her book, When Yellow was Black: The untold story of the first fight for desegregation in Southern schools will be published by Beacon Press in 2015.