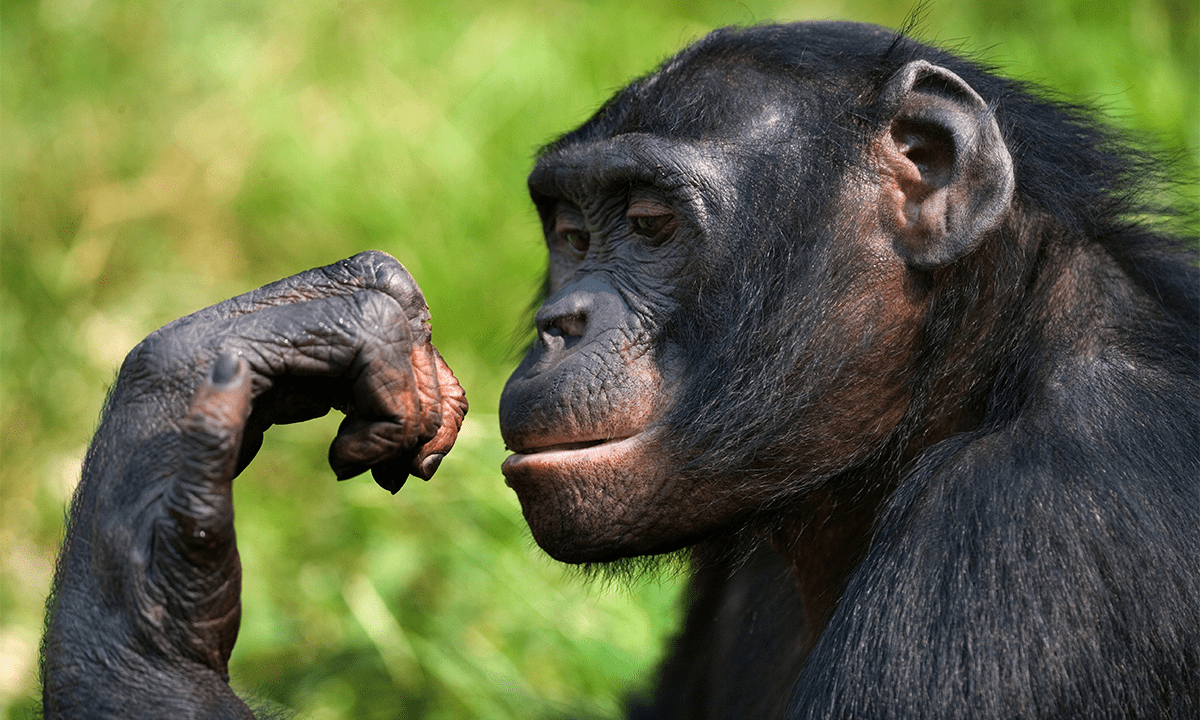

Animals must be resourceful to survive in Botswana’s harsh Kalahari Desert. For meerkats, that means looking out for one another. These social members of the mongoose family live in cooperative family units, called “mobs,” that can number up to 50 adults and pups. When meerkats forage for grubs, termites, scorpions, poisonous millipedes, and other invertebrates, they do so together. Periodically, one stands sentinel on a higher point to scan for threats, adopting a posture similar to that of the meerkat captured in this image by wildlife photographers Marie-Luce Hubert and Jean-Louis Klein.

When a sentinel spies something of concern, it musters its versatile voice to protect the mob. Meerkats are among the most vocal of all mammal species. Their range of some 30 types of calls includes one that specifically warns their brethren of the approach of a ground predator, like a jackal, while another indicates that a raptor like a tawny or martial eagle is flying overhead. Meerkats have yet another call that warns of snakes or rival meerkats, summoning the mob to gather and fight the foe, rather than flee to the nearest burrow. Meerkats can even signal the relative urgency of a threat—their voices more harmonic if the threat is low, and harsher and louder if high.

Meerkat cooperation arises from a “despotic” reproductive arrangement.

But they don’t chat only in times of distress. Meerkats also keep track of each other’s locations with a special call while roaming, for example. And each morning, members of a meerkat mob will gather together to face the sun and murmur “sunning calls,” which they carefully sequence to avoid interrupting one another, almost like a conversation.

That might sound warm and fuzzy, but meerkat cooperation arises from what researchers have dubbed a “despotic” reproductive arrangement. As with social insects like bees, a single meerkat “queen” dominates breeding behavior within the mob and forces subordinate meerkats, many of them her offspring, to help raise her pups rather than having their own. She enforces her reign with aggression driven by testosterone levels that surge past male meerkat levels when she is pregnant—viciously competing for food, attacking and sometimes evicting other females, and killing their pups, should they have any. Research led by Christine Drea through Duke University has even shown that this aggression can pass from the queen to her pups, who maintain their place in the hierarchy by acting, in the words of a Duke press release, like “spoiled little brats.”

Considering that a queen meerkat may have as many as three to four litters per year over 10 years, that’s a lot of entitlement for her subordinates to bear. Interestingly, though, the despotic system also seems to put a serious strain on the queen. Dominant meerkat females tend to have significantly more intestinal parasites than their subordinate mobsters. While that could simply be because they have more contact with other meerkats, what with all the tussling they do to maintain power, it could also be the result of a more insidious actor that can deplete anyone’s immune system: stress. ![]()

This story originally appeared in bioGraphic, an independent magazine about nature and regeneration powered by the California Academy of Sciences.