Sardines are never solitary. Even in death they are squeezed into a can, three or five to a tin, their flattened forms perfectly parallel. This slick congruity makes sense. In life, sardines are evolved for synchronicity: To avoid and confuse predators, they pack seamlessly together with thousands of other sardines into ball-like configurations. In these formations, no individual stands out. The shimmering, swirling mass of fish moves as one, fluid like mercury, molding and remolding itself into new shapes.

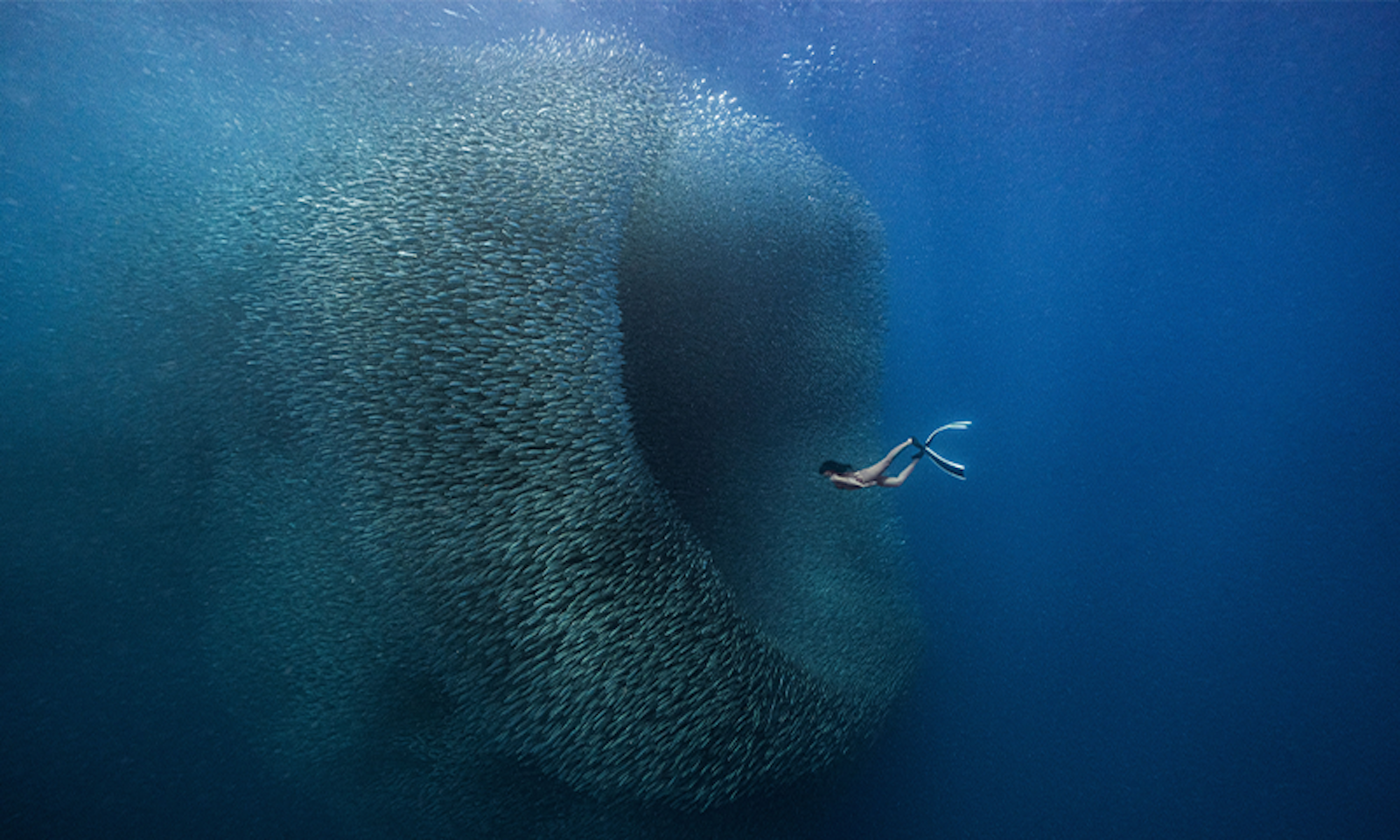

A sardine ball is the subject of the arresting image pictured here. It won the audience prize during the UNESCO Ocean Decade Week in Barcelona, which ran from April 8-12. Underwater photographer Ben Yavar captured the image off the coast of Moalboal in the Philippines in all its hypnotic plentitude. In the shot, a lone freediver approaches the ball, which responds by wrapping itself into a kind of portal, with a dark, empty core void of fish. The fish perceive the diver as a predator and dart outward to the perimeter in perfect unison. At the edges, they catch sunlight like a mesh of scattered pennies.

They risk pushing the population into a precipitous downward spiral.

The feast of sardines in the image is deceptive: Sardine fisheries are experiencing precipitous declines in catch throughout the Philippines. In the Sulu Archipelago, directly south of where the photograph was taken, sardines are a staple source of protein for the locals and help drive the economy. They make up more than 50 percent of the total fish catch. But sardine harvest in this region dropped by more than 26 percent between 2010 and 2019, due to heavy fishing pressure and rapid environmental changes that impact sardine habitats. The impacts are localized and vary along the jagged coastline. In some areas warmer waters stratify and prevent nutrients from surfacing from the deep, which impoverishes the feeding grounds of the fish. In other locations, more powerful currents disturb the customary tranquility of the nursing grounds. Climate change has increased the frequency of severe weather events in the region, which pressures fisheries to intensify their catch during favorable windows, often in disregard of sustainability guidelines.

“It’s very clear that the sardine stocks are overfished,” says Wilfredo Campos, a professor in marine biology at the University of the Philippines Visayas. A science-based management plan was recently approved by the government, requiring all fisheries to de-escalate levels of catch in the shifted nursing and feeding grounds by March 2024. It is too early to tell whether the new measures are being implemented or whether they are sufficient to allow sardine stocks to recover.

The history of sardine fishing is littered with cycles of boom and bust. In California, the collapse of the sardine fishery following WWII has been written into American folklore. In the 12 seasons prior to 1946, sardine landings averaged 600,000 tons per season, despite warnings from fishery biologists that the population could sustain only a third of this withdrawal.

In his novel Sweet Thursday, John Steinbeck wrote, “The canneries themselves fought the war”—removing fishing limits and catching all the sardines—“It was done for patriotic reasons.” In 1946, the catch abruptly dropped by 40 percent and was decimated by 1962. The fisheries closed in 1968. As the North American market folded, sardine fisheries in Peru and Chile took their place and became subject to the same patterns of overfishing, collapsing in 1990.

In the decades since, the science of fisheries management has become well established, particularly for bait fish like sardines, anchovies, and herring, which have predictable life cycles and well-understood ecology.

But a warming ocean is complicating attempts to turn back the ongoing sardine crisis in the Philippines: It shifts the pattern of nursing and feeding grounds for the fish, both of which are sensitive to temperature, and requires that fisheries adapt quickly. These operations must give fish the room they need to grow and reproduce before harvest. Otherwise they risk pushing a population into a precipitous downward spiral.

Speaking of fishing grounds in the north of the country, Campos says, “More than three fourths of the catches in Bulan fall below the size of first maturity. Many juveniles are caught in this area,” which undercuts the shoal’s potential to recover from a population decline.

Yavar’s image has staying power. It captures the true scale of sardines in their native environment, the endless blue, where we are visitors. It also preserves a rare interaction, a shared moment between a shoal and a person that does not revolve around consumption. It is food for thought. ![]()