If we could talk with whales, should we? When scientists in Alaska recently used pre-recorded whale sounds to engage in a 20-minute back-and-forth with a local humpback whale, some hailed it as the first “conversation” with the cetaceans.

But the interaction between an underwater speaker mounted on the research boat and the whale, which was described last year in the journal PeerJ, also stimulated a broader discussion around the ethics of communicating with other species.

After the whale circled the boat for a while, the puffs from her blowhole sounded wheezier than usual, suggesting to the scientists aboard that she was aroused in some way—perhaps curious, frustrated, or bored. Nevertheless, Twain—as scientists had nicknamed her—continued to respond to the speaker’s calls until they stopped. Twain called back three more times, but the speaker on the boat had fallen silent. She swam away.

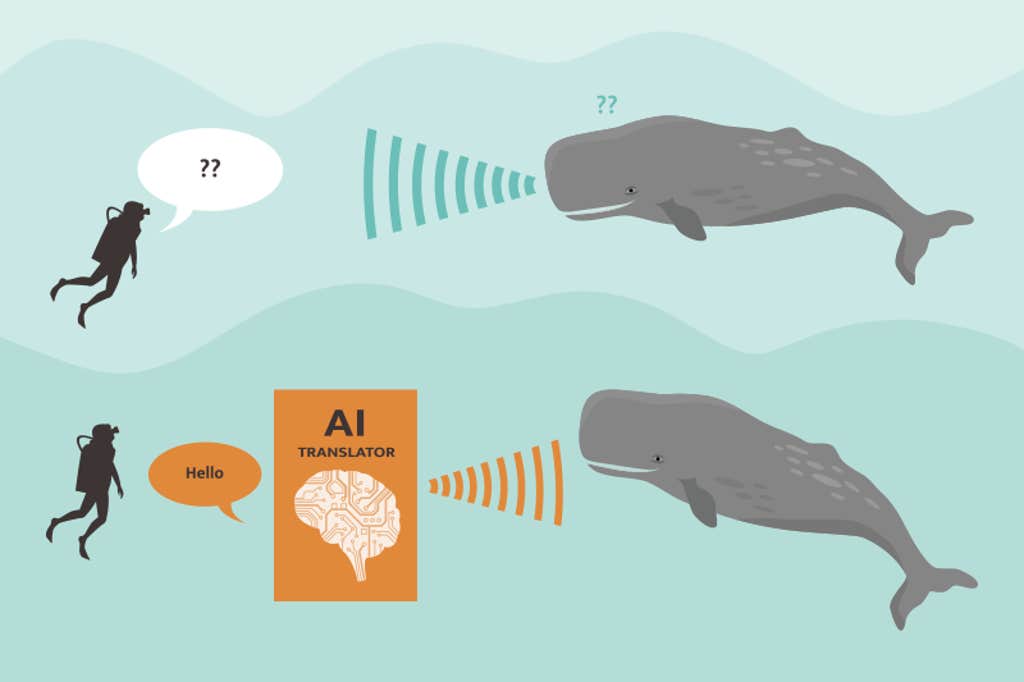

Scientists have used recorded calls to study animal behavior and communication for decades. But new efforts—and technology such as artificial intelligence—are striving not just to deafly mimic animal communication, but also to more deeply understand it. And while the potential extension of this research that has most captured public excitement—producing our own coherent whale sounds and meaningfully communicating with them—is still firmly in the realm of science fiction, this kind of research might just bring us a small step closer.

The work to decipher whale vocalizations was inspired by the research on humpback whale calls by the biologist Roger Payne and played an important role in protecting the species. In the 1960s, Payne discovered that male humpbacks sing—songs so intricate and powerful it was hard to imagine they have no deeper meaning. His album of humpback whale songs became an anthem to the “Save the Whales” movement and helped motivate the creation of the Marine Mammal Protection Act in 1972 in the United States.

In his later years, Payne became a principal advisor to Project CETI—short for the Cetacean Translation Initiative—founded by marine biologist David Gruber, which is working to decipher sperm whale vocalizations. It has a mirror effort in Whale-SETI, which is doing much the same for humpback calls and which conducted the experiment with Twain. Gruber and the behavioral biologist Brenda McCowan of the University of California, Davis, who is part of the Whale-SETI team, both say they hope that understanding whale vocalizations will spark additional public empathy and drive efforts to protect them from human threats, such as underwater noise pollution, ship strikes, entanglements in fishing gear, and continued whaling in some parts of the world, much as Payne’s earlier work drove pervious conservation efforts. “Just imagine what would be possible if we understood what animals are saying to each other,” Payne wrote in Time Magazine in June 2023, shortly before he died. “What occupies their thoughts; what they love, fear, desire, avoid, hate, are intrigued by, and treasure.”

Scientists plan to use AI to help parse out patterns in whale vocalizations.

Understanding whale communication could also strengthen the case for legal personhood, a fight animal rights advocates have usually lost. Courts often reject the idea of animals having rights on the premise that human beings are unique in being able to reason, feel, and speak. That stance could weaken if scientists can demonstrate that sperm whales, for instance, not only have complex communication but also vocally express alarm and suffering when exposed to the din of maritime traffic, says César Rodríguez-Garavito, an environmental law expert at New York University and the founding director of NYU’s More Than Human Life Project. As our knowledge of animal capabilities evolves from sentience to intelligence and potentially “language,” “then the threshold of protection also is raised, and you can offer a more expansive argument for the protection of those animals as legal subjects,” he says.

Understanding whales could also much more clearly elucidate their best interests, says Lori Marino, an expert in animal intelligence who founded the non-profit Whale Sanctuary Project. “I think it would be extremely important for captive whales and dolphins, because they would be able to tell us whether they like being in a tank or not,” she says, although she adds that there’s already enough evidence that their welfare and health suffer in such situations.

But there is an important difference in deciphering to listen—and deciphering to talk back.

Playing recordings of natural vocalizations has been a common way to study animal behavior and communication for decades—including in whales and dolphins—but it carries risks. Certain sounds might inadvertently confuse whales, potentially impacting the navigation of species like sperm whales that use clicks and the resulting echoes to navigate. It could lead individuals astray or disrupt important cooperative activities like hunting. Playing certain calls—for instance those of dead relatives—should be approached cautiously as it could cause emotional harm, experts note. Playing distress calls or vocalizations of predators such as orcas might also cause whales to suffer psychological stress or exert undue energy trying to escape.

Playing any vocalizations that could cause states like fear, anxiety, stress, or sadness should be off limits, says Marino. “We just need to be very careful with what the potential might be, because we may not know what it is that we’re actually conveying.”

Researchers involved in understanding whale communication stress that it’s still early days. Scientists know some things about whale vocalizations, having recorded their songs, clicks, whistles, and calls for decades. They know that many species, such as humpbacks, differ geographically in their vocalizations—a phenomenon akin to local dialects—sometimes picking up songs from their neighbors. Many sounds seem to be of social nature, helping identify individuals, facilitate social bonds, and aid in cooperative activities. But scientists don’t know much more beyond these basic functions—other than that cetacean communication appears to be complex and very different from human language. Many researchers avoid calling it “language” altogether because it seems to lack the basic organizational structures associated with human speech.

Scientists working to analyze whale calls plan to use artificial intelligence to help parse out patterns in the vocalizations. The next step is to determine how and whether these patterns relate to meaning. Project CETI, the furthest along in these efforts, is still working on the first phase, says Gruber.

While Gruber believes it’s possible to decode sperm whale vocalizations without playing natural recordings back to whales, McCowan says she doesn’t see any other way to decipher the meaning and function of whale sounds. Even with the best AI techniques to sift out patterns in the vocalizations, she says, scientists would still need to test them on individuals in the wild.

In a recent paper in Biological Conservation, two ethicists outline several concerns when it comes to talking to the cetaceans in “Whale”: either playing vocalizations—whether these be recorded or AI-generated, artificial whale phrases in order to study whale vocalizations—or potential future attempts to actually communicate with them.

AI ethicist Mark Ryan of Wageningen University in the Netherlands and environmental ethicist Leonie Bossert of the University of Vienna in Austria argue that scientists engaging in such research should carefully weigh the potential risks and benefits to whales. Technologies that help us understand whale communication could be a boon to science and whale conservation, they say, but only if used wisely.

Personally, me—David—I don’t have anything to say to a whale.

Animal behaviorist Josephine Hubbard of the University of California, Davis, who works with McCowan on Whale-SETI, says that playbacks are generally ethical as long as there’s reasonable certainty that a vocalization won’t elicit a negative response—and immediately terminate an experiment if it does—and as long as the scientists performing them have a specific hypothesis about the function of the vocalization in question, and are not simply belting out random whale noises just to see what happens.

For instance, with Twain, the team tested a “whup” call they had recorded the day before, a sound scientists believe signals an individual’s location. What was going through Twain’s mind, though, is impossible to know, McCowan says. All she can say is that Twain was clearly engaged with the recording, and that perhaps the reason she was circling the boat was to identify the source of the sound. “I highly doubt that Twain thought that she was talking to another humpback because there were no other humpback whales where that speaker was,” McCowan says.

There may be a possibility that someday AI will generate synthetic whale sounds, which could be similarly used in playback experiments to understand the function of whale vocalizations. This carries greater risk than playing back recorded vocalizations, as researchers will have even less control over the signals they send, says Frants Jensen, a behavioral ecologist of Aarhus University in Denmark, who studies cetacean communication. A call might, unbeknownst to us, mimic an alarm signal or even resemble the call of a dead relative. “If we really want to use generative AI for generating new signals for playback experiments, we need to be wary of what those algorithms actually produce and whether it could have similarities to sounds that animals have already evolved to have negative association with,” he says.

Ryan and Bossert acknowledge that this research may be beneficial to whales—if ethical pitfalls can be avoided. They caution against relying on the notion that new technology will solve the problem of whale conservation, without humans first addressing the threats they already pose to whales. It is important to consider the ethics of developing and employing such technologies before they become available, they say.

At the moment, there are no laws and few ethical frameworks that explicitly guide such whale vocalization research, although Whale-SETI and Project CETI are both working to craft ethical principles; Project CETI is working with NYU’s More than Human Life project to do so. Efforts to establish ethical guidelines should be grounded in legal standards like the precautionary principle, Rodríguez-Garavito says—meaning that scientists should tread carefully and do their best to ensure that activities aren’t causing harm. While Marino says the scientists she knows at Project CETI, Whale-SETI, and some other groups deciphering whale vocalizations are proceeding with the best interest of whales in mind, that doesn’t mean that everyone else will; she thinks there should also be laws to stop ordinary people from going out into the sea and broadcasting whale recordings.

If researchers do manage to get a handle on the meaning of whale vocalizations—with or without using playback experiments—the question remains what we should do with that technology. The scientists interviewed for this story said that they’d want to use it to benefit whales.

We should want to protect whales because of who they are rather than because of how similar they are to people.

Diana Reiss, a marine mammal scientist at the City University of New York’s Hunter College, points to at least one example when playing sounds has already helped save a whale: In 1985, a humpback whale swam into San Francisco Bay and about 70 miles inland, where he became stuck. Playing sounds of humpback-hunting orcas to drive the whale towards sea didn’t have much effect, and loud noises created by banging on pipes only helped get him out of shallower waters. A rescue team finally managed to lure him back to the ocean with recordings of humpback whales, Reiss says. “At the very end, he actually came over to our boat and rubbed his belly against our boat before he left.”

Perhaps, with the help of AI, scientists can identify whale signals to more effectively bring endangered whales to safety or direct them away from fishing nets or shipping lanes. Some AI projects are already learning to listen for killer whales in the Salish Sea so that ships can be diverted out of their way. AI could also identify distress calls in dolphins to detect strandings before they occur.

Being able to have a meaningful, lengthy conversation with a whale is a big leap further, however, and may never be achievable. But if it were possible, many scientists see the main potential value in whales being able to tell us how they feel, not the other way around.

“Personally, me—David—I don’t have anything to say to a whale” for the sake of it, Gruber says. “I really just want to hear and I want to know more about them,” he says.

Learning to understand “Whale” could provide a unique window into whales’ lives, but only if scientists keep an open mind about the mammals, Ryan and Bossert warn, and avoid interpreting whale vocalizations in human terms when working to decipher them. In other words, Bossert says, we should want to protect whales because of who they are rather than because of how similar they are to people.

“As we’ve done so much harm to these animals in the last centuries, I think you could say that we now have an obligation to protect them and to benefit them,” Bossert says. That, she says, is “what we should really use [this technology] for.”

Each step of the way, Bossert says, scientists should ask who is benefitting from the experiment. “We have to also,” she adds, “discuss if at some point it wouldn’t be better for the animals to just be left alone by us.” ![]()

Lead image: Benjavisa Ruangvaree Art / Shutterstock