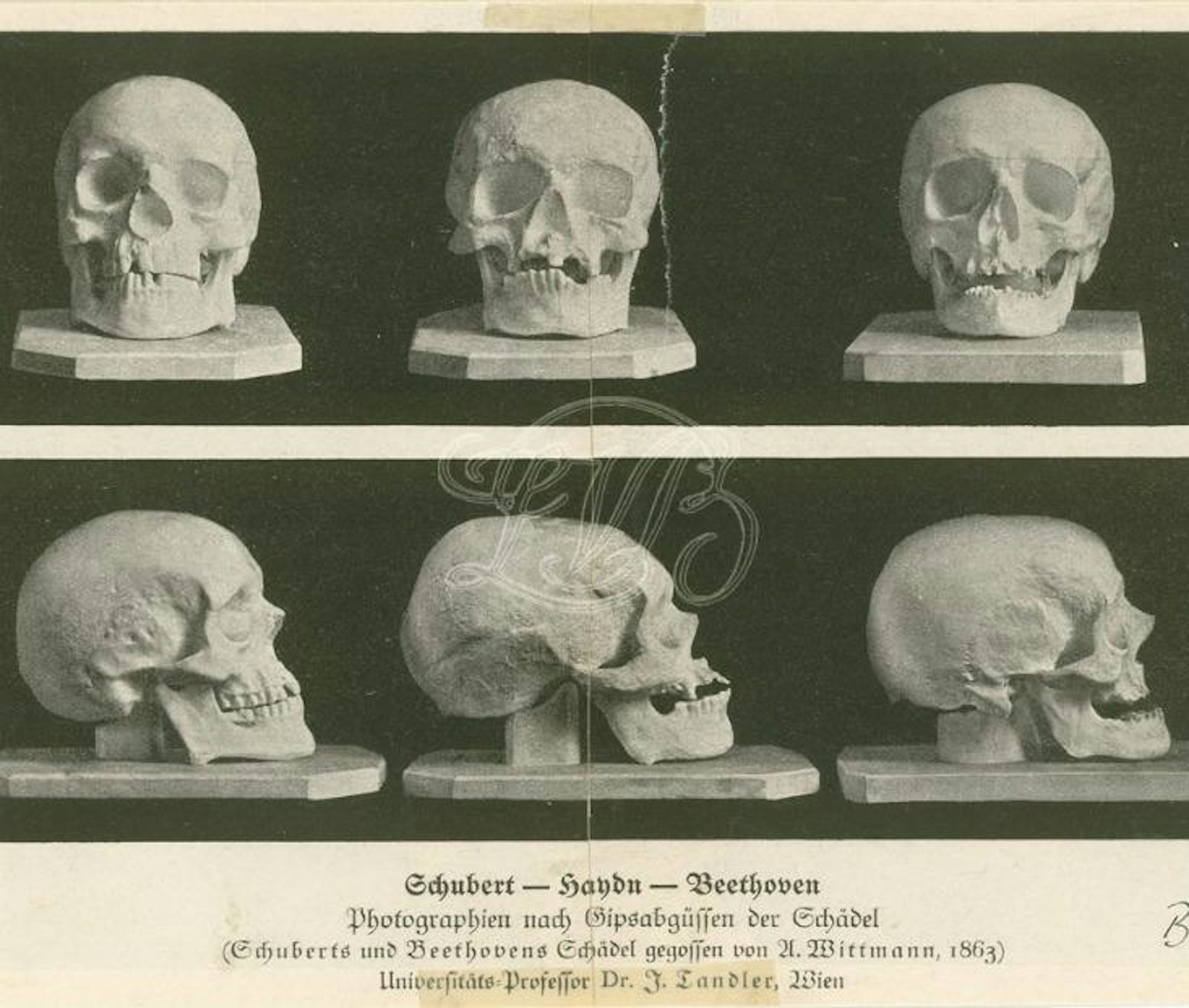

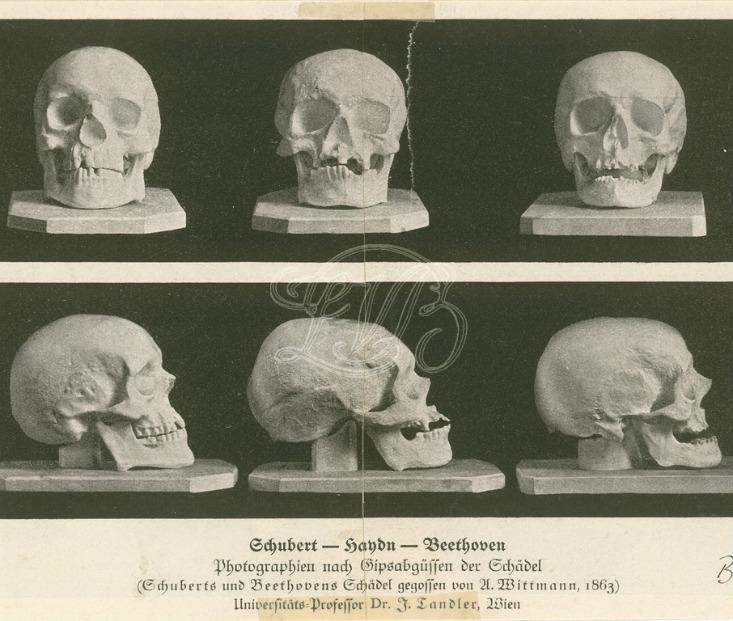

On May 31st, 1809, famed composer Joseph Haydn died, and he was soon buried in a simple ceremony—but his peaceful rest would not last long. Five days after his interment, a friend of his dug up his body and cut off his head. Joseph Carl Rosenbaum kept a detailed dairy chronicling his theft, noting that when he got into the carriage after severing the head, it smelled so bad that he almost vomited. It wasn’t until 11 years later, when Haydn’s body was to be moved to a different grave, that the authorities discovered that while the composer’s body remained in the coffin, all that was left of his head was the wig he was buried in.

As strange as this may sound, Haydn is far from the only man to have had his head stolen. When Mozart was buried in a mass grave, the cemetery’s rector tied a piece of wire around his neck so when the cemetery was retrenched he could correctly identify—and take—the skull. Painter Francisco Goya’s skull was swiped some time in between his death in 1828 and his exhumation in 1898. Philosopher Emanuel Swedenborg’s skull was stolen by naval officers after his death in 1772. British polymath Sir Thomas Browne’s head suffered a similar fate. Though short-lived, this trend of cranioklepty was a kind of obsession—the desire to acquire and understand a person’s life through their skull.

You won’t find much about the theft of Haydn or Mozart or Goya’s skulls in their biographies. Historians tend to nod quickly at the fact that their heads were stolen, and move on to the less gory details of their lives. Not writer Colin Dickey. “I’m fascinated by things that nobody likes to talk about,” says Dickey, who authored Cranioklepty: Grave Robbing and the Search for Genius. The book makes clear that cranioklepty, a term Dickey coined, is not merely a quirk of history—it actually tells us a lot about how people thought about human brains and bodies in another era.

According to Dickey, the cranioklepty trend was driven by two simultaneously emerging ideas. The first was phrenology. In the early 1790’s, Franz Joseph Gall began to popularize the idea that you could tell a lot about a man’s brain by looking at his skull. His logic went this way: different parts of the brain do different things—Gall called these different regions “brain organs.” And either by innate talent, or by using those different brain organs to different degrees, they might grow larger or smaller. When they changed size, they would leave a pattern of strength and weaknesses on the skull. Thus, by reading the bumps on someone’s skull, you could tell things like how religious a person might be, how angry they were, how well they could concentrate, and so on.

“He really felt as though he was doing a great service by desecrating this great man’s corpse so that his head could be preserved.”

At the same time that phrenology was emerging, the idea of genius was changing. Previously, genius was definable and concrete. Someone like Shakespeare might think of his work like a trade or craft—something that was teachable, definable, measurable. And this was how people saw most genius—as a learned, honed skill. So understanding genius was simply a matter of understanding craft, of examining and appreciating a product. But philosophers in the late 1700’s were beginning to see genius as something else. The genius of Haydn and Mozart and even Shakespeare seemed intangible, impossible to pin down. Simply reading Julius Caesar or examining the music of Haydn’s “Surprise” symphony wouldn’t truly tell you anything about their genius.

“So the idea of taking a skull of a famous person—not just a famous person but specifically an artistic genius—would be mediated by a desire to try and make visible that ineffable, invisible quality of genius that you couldn’t do from the works themselves,” Dickey told me in a recent interview. For Rosenbaum, having Haydn’s skull was a matter of capturing and honoring the slippery genius of Haydn’s music. “He really felt as though he was doing a great service by desecrating this great man’s corpse so that his head could be preserved,” Dickey says. Pulling it from the grave and presenting it in a nice glass case was a way of both showing off the skull and respecting what it represented: genius. The same likely goes for those who swiped Mozart’s, Goya’s, Swedenborg’s, and Browne’s skulls.

Eventually, as phrenology fell out of favor and medicine got better at preserving soft tissues like the brain, cranioklepty slipped into the past. But the underlying premise isn’t gone. Today, instead of displaying skulls, we obsess over brains. Einstein’s brain was stolen and driven around in a car for years. The brains of patients like H.M. are frozen and sliced into thousands of sheets, each thinner than a piece of paper, to milk every last drop of information out of them. “It’s now brains instead of skulls and neuroscience instead of phrenology,” says Dickey. We haven’t lost our obsession with how brilliant people think—we just think about their thinking differently.

Rose Eveleth is Nautilus’ special-media manager.