Everybody has that one story they tell. That one incredibly unlikely thing that, had it not happened to them, they might not even believe. They found the only other person on a deserted mountain in China, and it was a long-lost friend from high school. They escaped being struck by lightning only because they dropped something and climbed down from a ladder. They opened someone else’s locker because the lock had the same combination as theirs, and didn’t notice because the clothes inside were so similar. Everybody has had experiences that, if you read them in a book, would just seem too unlikely to be believable. “Truth is stranger than fiction,” said Mark Twain.

We know you have stories like this—and we want to hear them. What’s the most unlikely thing to ever happen to you? Tell us in the comments, or by sending an email to theunlikely@nautil.us, and we’ll compile your stories and pick the very best ones to feature on the site.

Below is a nice example of an unlikely story by journalist and Nautilus contributor Brandon Keim, republished from his own site, to get your memory going.

One winter morning two years ago, I visited my favorite bookstore. It was—past tense, as it closed that spring—a cozy place that struck just the right balance between old and new, rare and common, the sort of place you visit to just be around books. Every few weeks I’d go in the hopes of finding something I’d overlooked on all my other visits … which, inevitably, was the case.

On this morning I was looking for books by John McPhee, my favorite writer. I’ve read most of his works, but they happened to have a copy of Coming Into the Country, his account of life in Alaska, which I’d borrowed from a friend, lost, and consequently never read.

I lingered by one of the shelves as a young woman brought her selections to the counter. One of the books was of the mountaintop-air-crash-saga-of-survival genre. I don’t remember the author, but Ginger, who never let a customer go unedified, remarked that he was very similar to John McPhee. The girl replied that she loved McPhee and was a journalism student at the University of Maine, where her class had recently participated in a conference call with him.

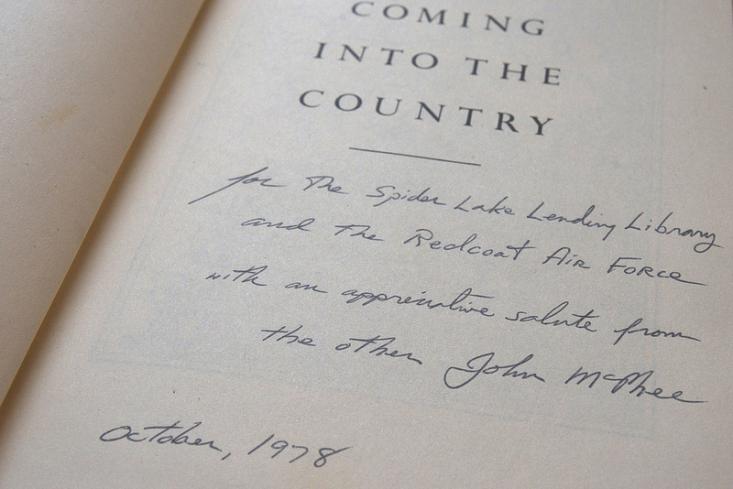

What a lovely coincidence, I thought! As she left, I gave Ginger my own McPhee find, and she said it was $30. Why so much, I asked? It was a signed copy, she said. I looked at the inscription:

Spider Lake is deep in the north Maine wilderness, not far from Allagash Lake, where John McPhee, floating in a canoe just after ice out in the 1970s, received a float plane visit from a certain state game warden who’d written him several years earlier, lamenting the inconvenience caused by the author’s now-famous name—since his own name, too, was John McPhee.

“His uniform jacket was bright red, trimmed with black flaps over the breast pockets, black epaulets. A badge above one pocket said “STATE OF MAINE WARDEN PILOT.” Above the other pocket was a brass plate incised in block letters with his name: JOHN MCPHEE. I almost fell into the lake.

He was an appealing, friendly man, and he did not ask for my fishing license.”

McPhee memorialized McPhee in a New Yorker essay entitled “North of the C.P. Line,” describing this alternate-universe version of himself who in so many ways lived a life he wished for himself: immersed in nature and wise to it, rescuing hunters and catching poachers, keeping track of fuel by instinct rather than dial, calling moose and catching brook trout.

The “Redcoat Air Force” was, I believe, a nickname the plane-flying wardens had for themselves. How did the book end up in my hands? The unfortunate, inevitable end to every story, perhaps—much of Lippincott’s library came from estate sales—but I like to think some karmic hand reached down and graced that great coincidence with one more.