Just over 100 years ago, on the 28th of June, 1914, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary was assassinated in Sarajevo. That set into motion a chain of events that, within several weeks, culminated in the European great powers declaring war on each other. The resulting conflict killed 37 million people.

Once the fighting started, a stalemate emerged on the Western Front, between Germany on the east and the Allies on the west. Both sides hunkered down in trenches, and it was nearly impossible for either side to make any significant progress against the other. With machine guns and artillery on both sides defending the trenches, attackers were quickly mowed down before they could cross “no-man’s-land,” the short distance between the opposing lines.

“The deadlock on the Western Front forced armies to develop new technologies to overcome it,” says Paul Cornish, a historian at the Imperial War Museums in London. Many well-known innovations that we associate with the war today were invented to try to gain an advantage over an entrenched enemy.

“The development of the tank, of poison gas, aerial photography, and sound ranging [a method to determine the coordinates of the enemy from the sound of its guns] can all be seen as efforts to break the trench stalemate,” says David Stevenson, professor of international history at the London School of Economics. Each new innovation that gave a slight edge over the other side would then be promptly copied and improved to make it even more deadly. The use of Chlorine gas led chemists to later develop phosgene and mustard gas, for example.

“Arguably, [WWI] was the first war where science and technology were mobilized as part of the war effort,” says Jeff Schramm, a Missouri University of Science and Technology historian of technology. “Labs and people all over, at universities and in the industries, were working on stuff for the war. That was unprecedented.”

Here are six of the more surprising examples of the technical innovations that came from World War I:

1. Industrial Fertilizer

Shortly before the war, German chemists Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch developed a process to convert atmospheric nitrogen into a biologically available form—ammonia—using high pressure and temperatures. During the war, this allowed Germany to produce artificial nitrates used to create explosives, like TNT. Prior to this, their nitrates came from Chilean guano deposits, which produced a limited supply. Once the war broke out, says Schramm, Germany had only enough natural nitrates to last about six months. “Because of this new process, they could create explosives essentially out of the air, and the war was prolonged for years,” he adds.

As deadly as his invention proved to be during the war, Haber’s process today actually sustains one third of the population on Earth, as it allows the production of ammonia nitrate fertilizer from nitrogen gas. Nitrogen is a critical component of both our DNA and proteins, and it is by far the most abundant atmospheric gas, but it first has to be “fixed” into a different form before it can be used by living organisms. (Specifically, the nitrogen must be changed from oxidation state 0 to –3.)

In nature, microorganisms possessing nitrogenase enzymes perform the nitrogen fixing. The Haber-Bosch process permitted the mass production of nitrate fertilizers, which sustain mass-scale industrial agriculture today.

2. Drones

World War I caused a tremendous acceleration in the development of aviation. “During the war, air speeds and [altitudes] doubled, engine horsepowers quadrupled, and bomb payloads increased even more,” says Stevenson. The war also saw experiments in developing the first pilotless aircraft.

Charles Kettering designed an unmanned “flying bomb,” known as the Kettering Aerial Torpedo or the “Kettering Bug,” that could hit a target at a range of 40 miles. The craft was launched with a dolly-and-track system; once launched, an onboard gyroscope guided it to its destination. “It was the first cruise missile—or drone if you will—and it was designed to take off, fly for a certain distance, and then stop and dive into the ground,” explains Schramm. The first test flight on October 2, 1918, failed because the aircraft climbed too steeply, stalled, and crashed.

Elmer Sperry and Peter Hewitt developed an unmanned aircraft for the US Navy in 1916 and 1917, known as the Hewitt-Sperry Automatic Aircraft. It was just 18.5 feet across and weighed 175 pounds, and it was also piloted with gyroscopes and a barometer to determine its altitude. It flew its first test flight on Long Island on March 6, 1918.

In the end, both were determined to be too unreliable to be useful. Still, by the time the war ended, the US had produced 45 “Kettering Bugs.”

3. Air Traffic Control

Radio had already made its debut before the war, but great strides were made during the war because of how valuable it could be for military communications. Nowhere was this more apparent than in aviation. In the early days of flight, once pilots left the ground, they had no good way of communicating with each other or the people on the ground.

The US Army installed the first two-way radios in planes before the nation’s involvement in the war. By 1916 technicians could send a radio signal over a distance of 140 miles, and radio telegraph messages could be exchanged between planes in flight. By the end of 1916, a helmet was designed with a built-in microphone and earphones to block out noise from the aircraft’s engine; in the following year, the first human voice was transmitted by radio from a flying plane to an controller on the ground.

The two-way radio systems developed for airplanes and operators on the ground were not only invaluable to fighting of the war, but also became the basis for the technology that would develop into the air-traffic-control system of today.

4. Portable X-Rays

Battle casualties overwhelmed the medical services in 1914, but armies quickly developed sophisticated systems for addressing the problems with new innovations made during the war. For example, the Thomas splint for a broken leg had a massive impact on survival rates in an era before antibiotics. Before the Thomas splint was invented, 80 percent of all soldiers died from a broken femur, but by the time of a battle in 1917, over 80 percent survived, reportedly. Blood banks were developed, thanks to the use of sodium citrate to keep blood from coagulating and becoming unusable, allowing battlefield transfusions.

One of the most important medical innovations of the time was the ability to get the diagnostic tools to the front line. When the war broke out, X-ray machines were too bulky and delicate to move. Using funds she raised in Paris, Marie Curie developed small, mobile X-ray machines and installed them in cars and trucks for the French army. She drove some of these portable X-rays to the front herself, and worked with her 17-year-old daughter, Irene, at casualty-clearing stations, using the X-rays to locate fractures, bullets, and shrapnel.

5. Sanitary Napkins & Tissues

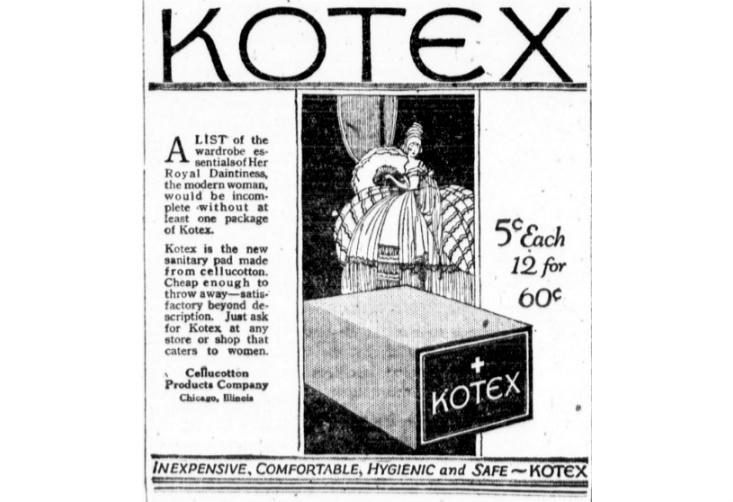

In 1914, Ernst Mahler, the head of a small US company called Kimberly-Clark, toured pulp and paper plants in Germany, Austria, and Scandinavia and spotted a new cellulose material called “Cellucotton.” It was five times more absorbent than cotton itself and, when mass-produced, half as expensive. Upon returning to the US, Mahler trademarked it; when the US entered the war in 1917, Kimberly-Clark started producing the wadding for surgical bandages.

Meanwhile, enterprising Red Cross nurses started using it for their own personal hygienic use. Once the war ended, Kimberly-Clark re-purchased the surplus of bandages from the military and the Red Cross and created the first commercial sanitary napkins.

The company also ironed out the cellulose material to make smooth tissues, which, in 1924, were released as the first facial tissues: Kleenex.

6. Sun Lamps

The undernourishment of Germans because of the war led an increase of rickets, a disorder caused by a lack of Vitamin D, calcium, or phosphate that leads to the weakening of bones. By the winter of 1918, half of the children in Berlin were suffering from rickets.

At the time, the cause of the ailment was not known, but a Berlin doctor named Kurt Huldschinsky noticed that the children were also very pale, so he conducted an experiment in which he put four children under mercury-quartz lamps that emitted ultraviolet light. The treatment worked: The children’s bones became stronger. Ultraviolet light causes the skin to produce Vitamin D, which is necessary for healthy bones. Thus, the sun lamp was born.

Simone M. Scully is a science and culture journalist based in New York City. Follow her on Twitter at @ScullySimone.