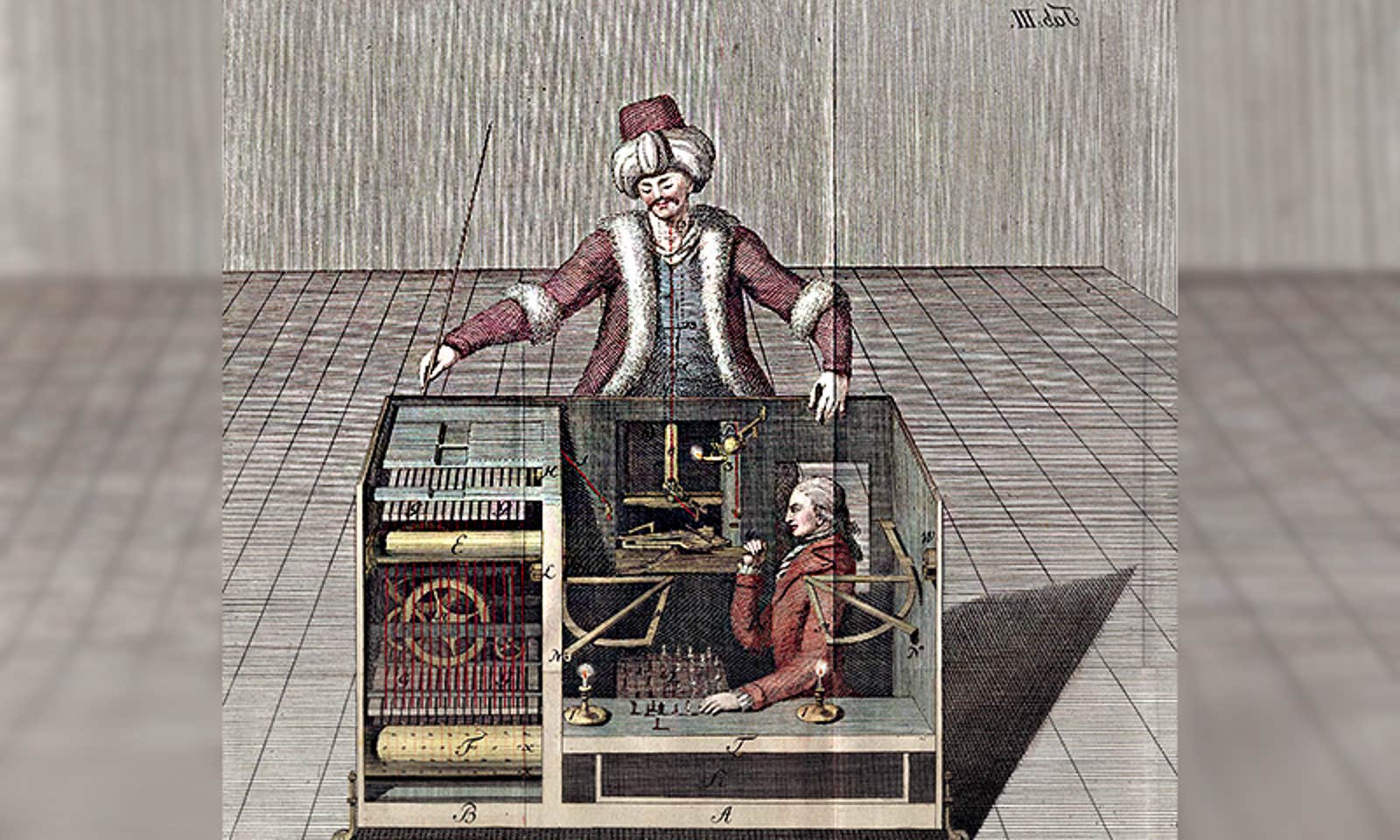

Wolfgang von Kempelen, the 18th-century inventor and author, once claimed to have created a chess-playing robot, called the Mechanical Turk. How was this possible, almost two centuries before computers were invented? Easy. By fraud.

The Turk was just a box containing a hidden chess master. Back then, the idea of an automaton that could play good chess was impossible. Even in 1997, when the IBM computer Deep Blue defeated the then-reigning chess champion Garry Kasparov, he suspected that one of the moves Deep Blue made during the game had actually come from a human.

How times have changed.

Since Deep Blue, the best chess playing entities have been computer programs, not humans. It’s trivially easy to cheat online, on platforms like Chess.com, where many people and some of the world’s best play. You simply have a chess program running off to the side and put your opponent’s moves in as your own, then move as the computer would against your opponent. You’re guaranteed to win. Unless, of course, they are cheating, too.

In September, Magnus Carlsen, the reigning five-time world chess champion, withdrew from an over-the-board match with Hans Niemann, a 19-year-old grandmaster, at the prestigious Sinquefield Cup in St. Louis. Carlsen accused Niemann of cheating. Niemann denied it, and admitted to cheating online just twice in his life—when he was 12 and 16 years old. An investigation by Chess.com, released on Oct. 4, states Niemann likely cheated in more than 100 online games.

In the Sinquefield Cup match, there was no hard evidence that Niemann had cheated against Carlsen. No device, speaker, computer, or wires have been discovered. How would it be possible? I’m reminded of the scene from Goldfinger, where someone cheats at cards with the aid of an accomplice with binoculars and an audio connection. You can fit a chess computer into a small, silicone-covered box the size of a small salt shaker. It buzzes to indicate where to move which piece, allowing one to have the chess computer on their person.

If Niemann cheated, he could have also recruited some conspirator to put Carlsen’s moves into a chess AI, and then communicate the recommended move via some device, hidden somewhere on Niemann’s person. Historically, others have cheated by having a vibrating device signal morse code from an accomplice watching the game or giving subtle hand signals from the crowd. This recent turmoil has caused some beefed-up security at chess tournaments, including allowing people to spectate only from another room with a 30-minute delay in the video, to thwart real-time assistance.

Chess.com found that Hans Niemann’s results in many online games were unlikely.

Many people seem sure that Niemann cheated somehow. Why? Carlsen’s suspicions carry weight. Niemann was playing unrealistically well, Carlsen said in a public statement. “Throughout our game in the Sinquefield Cup I had the impression that he wasn’t tense or even fully concentrating on the game in critical positions, while outplaying me as black in a way I think only a handful of players can do.”

If Niemann cheated, it may not have been on every move. For excellent chess players, the next best move is often relatively obvious. The player would only need to consult a chess AI at certain key points—as few as one or two—to beat their competitor. This is known as “selective cheating.” A savvy cheater might even make some low-cost moves they know are sub-optimal, just to throw cheater detectors off the scent.

In its report, Chess.com compared Niemann’s moves to that of Stockfish, the best chess AI out now. It’s so good it would probably beat Carlsen, or any other human player, every time. It can look over 40 moves ahead, far more than any human being. This means that chess AIs can make moves that humans never would—moves that look, to skilled chess players, like bad ideas in the short term but pay off further ahead in the game than human grandmasters can mentally simulate. Human chessmasters tend not to make such moves, and if they do, we might suspect them of cheating.

Chess.com found that Niemann’s results in many online games were extraordinarily unlikely, given his skill. They also looked at how long Niemann took to make the more difficult moves—if the moves are made too fast, it adds evidence to the idea that he was using an AI. This is similar to how “doping” is detected in sports: Contenders on drugs perform at inhuman levels of speed and strength.

In September, chess enthusiast Yosha Iglesias conducted an analysis of Niemann’s games using a program that estimates how close to optimal each move was. What Iglesias found supported Carlsen’s suspicions: Niemann’s moves were close to optimal. Most chess masters play at around 70 to 75 percent of optimality, and Niemann played at close to 100 percent over the course of several games. Clever Hans might be taking cues from outside his own mind.

Where once we had machines cheating at chess by using humans, now we have humans cheating by using machines.

An anti-Mechanical Turk. ![]()

Jim Davies is a professor at the Department of Cognitive Science at Carleton University. He is co-host of the award-winning podcast Minding the Brain. His latest book is Being the Person Your Dog Thinks You Are: The Science of a Better You.

Lead image: Humboldt University Library / Wikimedia Commons