When we think of life, we usually think of soft, squishy, and wet things. Or we might think of the “omes”: the genome, which carries our heredity code; or the proteome, which is the collection of proteins these genes assemble; or the metabolome, small molecules that facilitate our metabolic processes. These are the classical underpinnings of modern biology.

What we usually don’t think about is the metal counterpart, called the metallome. Where the other “omes” are full of complex structures and intricate biomachinery, the metallome is much simpler. It’s just a collection of metal atoms.

Nevertheless, it has done some remarkable things. It has enabled the chemistry at the heart of the other omes, acted as an interface between them and the changing environment of the Earth, and helped to drive the evolution of life itself for over 3 billion years.

This new “ome” deserves a position up there with the greats. It’s classic metal.

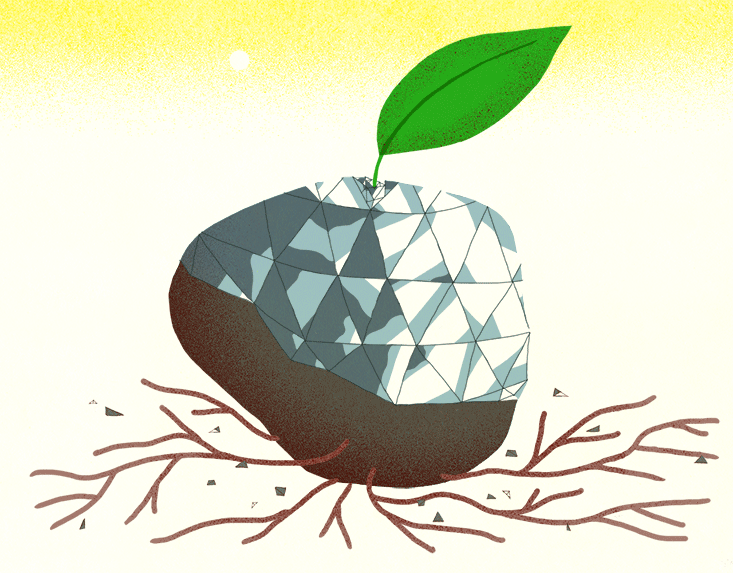

Consider the history of iron, one of the metals of the metallome. The early ocean was dominated by iron atoms that were doubly positive charged ions (Fe2+). They were highly soluble in water, and therefore available as a “nutrient” that could be used for essential catalytic functions by oceanic life, like single-cell cyanobacteria.

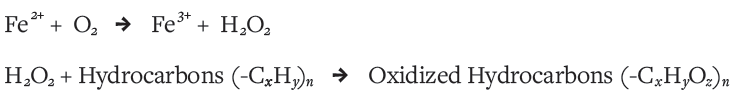

The iron was useful in more ways than one. These early lifeforms consumed carbon dioxide and sunlight to produce complex organic hydrocarbon molecules, and, as a byproduct, oxygen. Unfortunately, this oxygen was toxic to them. This is where the iron ions again came in handy: They scavenged toxic oxygen exhaled by the cyanobacteria into ocean water through an electron exchange process that produced triply charged iron atoms (Fe3+), and chemical species containing oxygen. The reaction looked like this:

This rescue by iron was also altruistic and self-destructive. The triply charged iron ions produced by the reaction readily formed iron oxide (Fe2O3) in the ocean waters, which is highly insoluble. As a result, iron precipitated out of the ocean and fell to the ocean floor as fine particles, greatly reducing iron concentrations in the ocean. This meant iron was no longer available to cells for their internal chemistry, toxic oxygen concentrations began to build up, and cyanobacteria began to die off.

This set up a boom-bust cycle in cyanobacteria populations, rather like a predator-prey cycle. As the cyanobacteria died off, less toxic oxygen was produced, oceanic iron concentrations recovered, and cyanobacteria populations recovered. We can see a record of this cyclic process in areas that used to be the sedimentary bottom of ancient oceans, in the form of exposed rock-containing layers of red iron oxide (Fe2O3) interspersed with gray layers of cellular debris from decayed cyanobacteria. These so-called banded iron formations are a geological record of the metallome at work.

The metallome didn’t just help early life to perform its basic functions—it also helped it adapt to a changing Earth. Around 2 billion years ago, the Earth experienced a Great Oxidation Event (GOE). The photosynthetic bacteria population grew enough to produce oceanic oxygen at a level high enough for it to escape into the atmosphere.

This was a pivotal event: The composition of the atmosphere changed dramatically as oxygen levels rose to near-modern levels. These high levels in turn increased the rate at which soluble Fe2+ was oxidized to insoluble Fe3+, but it also increased the rate at which ocean insoluble metallic sulfide salts (metals bound to sulfur) were oxidized to produce soluble sulfate salts (metals bound to sulfur and oxygen). As bio-available iron levels decreased, the availability of copper, zinc, and molybdenum all increased, as their salts became soluble.

This led to a host of changes in cellular chemistry. Where oceanic life had used tungsten as an oxygen atom transfer catalyst, it began to use molybdenum, which is actually a more efficient catalyst, but had been trapped in an insoluble form. The GOE also reduced oceanic iron concentrations, by transforming soluble iron (Fe2+) to insoluble iron oxide (Fe2O3). So cells adapted by putting an organic molecule coating on the surface of its iron ions, preventing them from being hydrated by water and precipitating out of the ocean as an oxide rock. This biological “M&M” was water-soluble and bioavailable to the cell. The M&M was made using organic sequestering agents called siderophores (from the Greek “sider” for iron and “phore” meaning carrying), and are still used by microbes for bringing iron into their interiors to this day.

There are many other instances of the metallome driving changes in the genome and proteome. Sea squirts, for example, bind and transport oxygen using a copper-containing protein called hemocyanin, while we humans use the iron-containing protein hemoglobin. This variety illustrates how the metallome gives life more flexibility in its evolution. There are mysteries, too. Sea squirts have evolved to concentrate vanadium in their cells by a factor of over a thousand, for reasons that remain unclear. Some suggest that vanadium may be involved in oxygen transport and respiration, but it’s not clear why hemocyanin isn’t enough.

The metallome is even changing how we think about life on other planets. The energy required to drive cyclic chemical reactions that are self-replicating—what we might call “life”—could come from reactions of the metallic elements. Our search for extraterrestrial life shouldn’t be restricted to a search for remnants of complex organic molecules. There’s another clear target, with a rather appropriately sci-fi ring to it: Heavy metals in space.

The Metallome

A list of life-supporting metals with illustrative biological functions.*

Sodium: nerve function, osmotic pressure balance, and charge stability of cell

Potassium: nerve function, osmotic pressure balance, and charge stability of cell

Magnesium: plant photosynthesis, structure stabilizer

Calcium: skeletal structure forming (teeth, bones), control signal trigger

Vanadium: catalyst for oxygen reactions, possibly involved in oxygen transport

Chromium: possibly involved in insulin function

Manganese: activator of certain enzymes, plant photosynthesis Iron: oxygen transport and storage, electron transport catalyst

Cobalt: cell division, a constituent of vitamin B12

Nickel: hydrogen activation, catalytic protection from toxic superoxide

Copper: respiratory chain electron transport catalyst, catalytic protection from toxic superoxide

Zinc: super acid catalyst, enzyme activator, blood pH control

Molybdenum: nitrogen fixation in plants, oxygen atom transfer catalyst

Tungsten: oxygen atom transfer catalyst

* This list contains metals that support essential life processes. The list is not meant to be complete for all organisms and not all organisms may require all of the above metals. However, some metallome elements are required by all living cells, such as iron, which is a necessary nutrient for more than 99 percent of all known cells. The metals of the metallome, while they serve specific life enabling functions, can also be toxic if present in the wrong cellular location at the wrong concentration. Hence the metallome, while essential, must be carefully controlled by the genome and proteome in a living system.

Al Crumbliss is University Distinguished Service Professor at Duke University, President-Elect of the International Biometals Society, and a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, American Chemical Society, and Royal Society of Chemistry.