On the morning of Friday Aug. 6, 1852, Alfred Russel Wallace was summoned to the deck of the brig Helen. The boat was in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, and Wallace had already been at sea for 26 days. He was used to hardship. He’d spent the previous four years in the Amazon rainforest, exploring uncharted territory and collecting natural history specimens for his own collection and for museums back home in England. The hold was filled with his valuable specimens—many were new to science and irreplaceable. The 29-year-old Welsh-born naturalist had even stowed several live specimens: there were parrots and parakeets, some monkeys, and a wild forest dog on board.

The captain said to Wallace, “I’m afraid the ship’s on fire. Come and see what you think.”

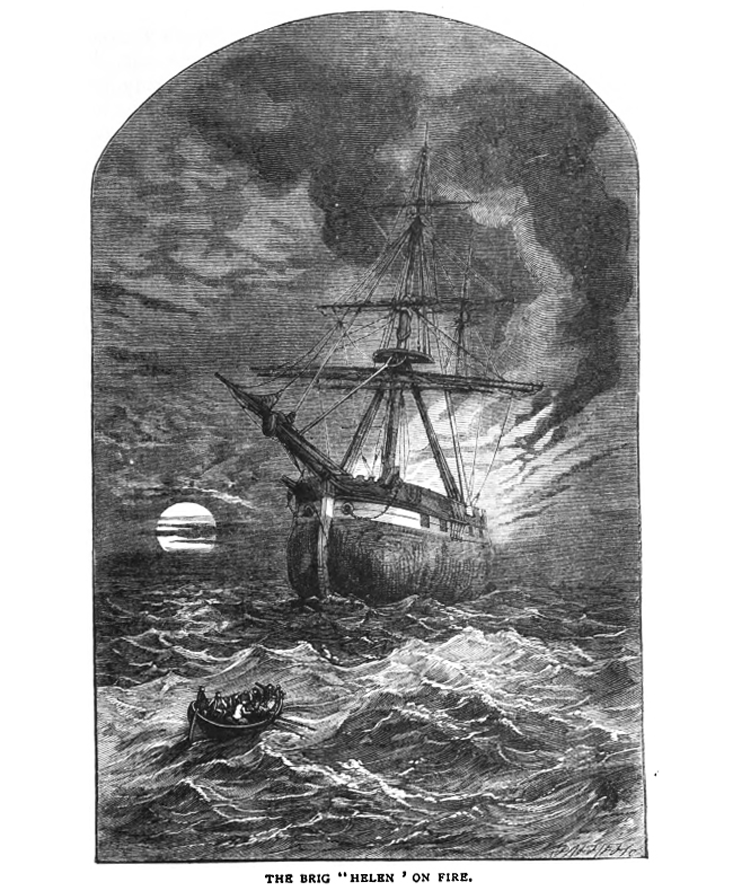

Ten months earlier, in the depths of the rainforest, Wallace had contracted a fever that almost killed him. Still sick, he now stood with Captain Turner on the deck of the Helen and watched as smoke billowed from the forecastle. The small crew frantically threw buckets of water into the hold, but the fire was unstoppable and engulfed the ship. The captain gathered up his chronometer, sextant, compass, and charts, and the crew began to prepare the rescue boats: a longboat and the captain’s gig.

“I got up a small tin box containing a few shirts,” Wallace recounted in a letter to his friend, the botanist Richard Spruce, “and put in it my drawings of fishes and palms, which were luckily at hand.”

The boats were quickly loaded with supplies: “Two casks of biscuit and a cask of water were got in, a lot of raw pork and some ham, a few tins of preserved meats and vegetables, and some wine.” Then the men clambered aboard. Gripping a rope to lower himself, Wallace slipped, stripping the skin from his hands, and fell into the boat. In time the Helen sank to the bottom of the Atlantic, taking with it an unknown diversity of new species Wallace had collected.1

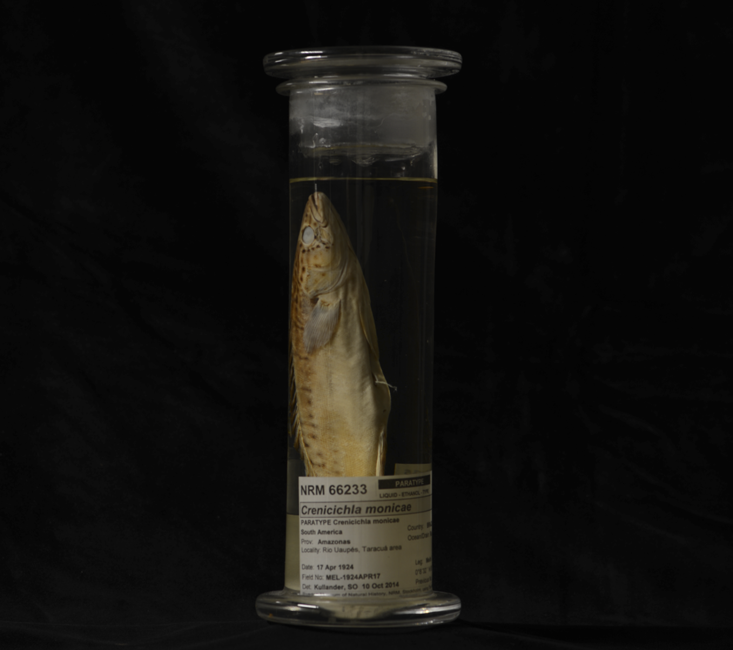

Finally, in September 2015 Sven Kullander, an ichthyologist at the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm, named one of the undescribed species—a distinctively patterned red fish. Wallace had collected the specimen from the Amazon basin in 1852. Kullander has given it the scientific name Crenicichla monicae.

“Crenicichla monicae belongs to a group known as pike cichlids,” says Kullander. All together, the genus includes almost 100 known species distributed across tropical and southern South America, east of the Andes. “Pike cichlids are elongate,” he says, “and most of them have a pointed snout and large mouth, reflecting their carnivorous habits.”

The fish has a long, spiny dorsal fin that runs almost the length of its body, and it grows to a length of about 10 inches. Above its lateral line, its long, narrow body is speckled and patterned with distinctive dark spots. Kullander’s descriptive paper, published in Copeia, is titled “Wallace’s Pike Cichlid Gets a Name After 160 Years: A New Species of Cichlid Fish (Teleostei: Cichlidae) from the Upper Rio Negro in Brazil.”2

Wallace was calm; he expected to die. As the fire sputtered into the ocean, he sat in the boat thinking of his lost specimens.

A major tributary of the Amazon, the Rio Negro is a black-water river that begins in southern Colombia and hairpins southeast through the rainforest. At Manaus, the Negro and the Amazon meet. Wallace had collected the fish upstream, on the swift upper reaches of the Rio Negro, sometime before 1852. At least one specimen of C. monicae was in the hold of the Helen when she sank, says Kullander. He knows this because of a pencil drawing Wallace made after he collected the fish. He’d worked as a surveyor and was trained to draw with great accuracy. As the ship burned and began to list, Wallace grabbed his drawings of fishes and palms and ran to escape the flames. When he fell into the boat, the drawings fell in with him.

A world expert on cichlids, Kullander is in his middle 60s and has a long silver ponytail and pale blue eyes. He’s been studying fish for more than 50 years. When he was still a high school student, he was given his own research space.

“I tried birdwatching, but it was boring,” he says. Instead, he settled on fish. In the 1970s Sweden saw a boom in the importation of African lake cichlid species as aquarium specimens. Suddenly more and more species were available, and some of them were uncommon forms. As a teenager Kullander took advantage of the opportunity and became an avid aquarist, maintaining tanks filled with exotic cichlids. “I tended more to the neotropical forms; however, I was very familiar with all the literature and kept all the species I could find,” he says. “I maintained a large correspondence with other hobbyists and scientists and neglected school as much as possible.”

He wrote his first academic papers without supervision as an undergraduate. Finally, during his graduate studies, Kullander was supervised by Bo Fernholm—at the time, the only fish taxonomist in Sweden. In all, Kullander has named more than 100 new cichlid species. Worldwide, he says, there are almost 2,000 known species of cichlids, found in Asia, Africa, and North, Central, and South America. Among other diagnostic criteria, ichthyologists identify new cichlid species by subtle differences in the pharyngeal teeth—two plates in the throat covered in beds of toothlike spines that come together to grind up food.

Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, but he didn’t form his theory of evolution in isolation. He had collaborated with people like Wallace, a quiet, bespectacled man who was the first to develop some of the fundamental theories of biogeography. It was Wallace who seemed to grasp intuitively the importance of geographic isolation of organisms in the process of speciation, and he shared those ideas with Darwin as they corresponded. For years Wallace had explored the darkest parts of the Amazon rainforest, collecting specimens like C. monicae. Later he also spent time in the Malay Archipelago, where he demarcated the Wallace Line—a theoretical boundary that runs northward through Indonesia and between Borneo and Sulawesi before veering northwest past the Philippines. Vastly different species are found each side of the line: Australasian species to the east, Asiatic species to the west. In places the barrier between the two ecozones is nothing more than a narrow channel of water. With very few exceptions, species are found either on one side of the line or on the other. Occasionally, in a region known as Wallacea, the line is less clear.

Back in 1852, Wallace and the other men sat in the rescue boats in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean and watched as the flames rushed across the deck and up the sails, consuming what was left of the Helen. “Soon afterwards,” he wrote, “by the rolling of the ship, the masts broke off and fell overboard, the decks soon burnt away, the ironwork at the sides became red-hot, and last of all the bowsprit, being burnt at the base, fell away also.”

Night came. The men in the boats stayed close to the burning ship as flames illuminated the black water. Sometime in the night the Helen rolled over in the waves—a great hissing cauldron of fire, the cargo burning in a liquid mass at the bottom. Wallace was calm; he expected to die. As the fire sputtered into the ocean, he sat in the boat thinking of his lost specimens: the forest dog; the jars filled with fish; the insects and parakeets; three woolly monkeys. “I had taken some trouble to procure and pack an entire leaf of the magnificent Jupaté palm (Oredoxia regia), fifty feet in length, which I had hoped would form a fine object in the botanical room at the British Museum.”

He stared at his hands, still raw and stinging from rope burns, and enumerated his specimens. “All of my private collection of insects and birds since I left Para was with me,” he wrote, “and comprised hundreds of new and beautiful species, which would have rendered (I had fondly hoped) my cabinet, as far as regards American species, one of the finest in Europe.”

In 1924 Melin and Vilars collected several specimens of a distinctive spotted red fish. It was the same fish Wallace had collected and then watched sink into the ocean.

It was all gone, but Wallace’s illustrations survived. Eventually they became part of the collection at the Natural History Museum in London. In 2002 they were published as Fishes of the Rio Negro. Plate 194 is a finely detailed black-and-white pencil drawing of Crenicichla monicae, with its long, spiny dorsal fin. The mouth is slightly open, and the back and upper body are patterned with dark spots. The fish, Wallace had noted, was distinctively red. With a dull crimson band along its sides, even its eyes are orange-red.

In the intervening years, most of the other cichlids in Wallace’s drawings had been identified—usually at least to genus and often to species. Many of the fish he drew were known before he collected them. They had been described in an 1840 monograph by Austrian ichthyologist Johann Jakob Heckel, who relied on specimens collected by Johann Natterer, a fellow Austrian who was part of an 1817 expedition to Brazil. He returned to Vienna almost 20 years later with an enormous collection of natural history specimens. Other species remained unknown. In 1989 Kullander described Acaronia vultuosa, another species Wallace had drawn in the Amazon. A few species waited even longer. Like the fish in plate 194.

In 1923 a group of Swedish biologists traveled to some of the same locations Wallace had visited 70 years earlier. There were three friends: Douglas Melin, Arthur Vilars, and Abraham Roman. Melin and Roman were biologists, and Vilars, an engineer, was their assistant.

From Manaus they ascended the Rio Negro northward. The river there is really a collection of channels traveling in the same direction. Where the Rio Uaupés meets the Rio Negro, they took the fork eastward along the Uaupés, into the darkness, tracing the tight turns of a swift brown river that grew narrower and more sinuous with every mile. They collected biological specimens along the way. By mid-1924 things had changed. Roman had left for Sweden in April. Vilars was dead by June—killed by a fever.

Melin then returned to Manaus, where he shipped specimens home before continuing as a one-man expedition in Peru. Together the biologists had collected thousands of specimens—frogs, catfish, jumping spiders, and numerous botanical samples. In April 1924 Melin and Vilars had collected several specimens of a distinctive spotted red fish from the Rio Negro drainage basin at Taracuá. It was the same fish Alfred Russel Wallace had collected and then watched sink into the ocean. Eventually, says Kullander, all the specimens from the expedition were sent to the Swedish Museum of Natural History.

“All together, the Melin fish collection was not a big one,” he says. It comprises 130 jars, each containing one or more specimens stored in alcohol. “People going on expeditions today take back thousands of specimens,” says Kullander.

Melin’s specimens of C. monicae remained unidentified in Stockholm. Slowly the red scales faded to pink and eventually to pale yellow. The eyes turned milky and opaque. Molecules in the specimen broke down and began to degrade. In the 1950s, ichthyologist Otto Schindler visited the collection in Stockholm, saw the specimens, and took them to the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology in Munich, where he worked as a curator. Again they sat unidentified for decades. In the 1990s Kullander found the specimens—still in Munich.

“I found these spotted fish, which I recognized must be something new,” he says. He took two of the specimens back to Stockholm but left a third one because it didn’t have any color. With the constellations of dark spots that mark its upper body and its long, spiny dorsal fin, the fish that Melin and Wallace both collected is unique among cichlids. From the handful of specimens that exist, says Kullander, the markings seem to be present only on females.

Perhaps there are other phantom fish too, suspended in jars in Stockholm and elsewhere.

“Most crenicichla species look very similar. … The distinctive color pattern of female Crenicichla monicae is very evident on Wallace’s drawing and enabled us to identify it as the spotted species in Melin’s collection.” Compared with its closest relatives, its long dorsal fin has an additional spine. Its pharyngeal teeth are different in important ways. And “unlike the majority of pike cichlids,” says Kullander, “in which the scales are rough to touch from small spines along the scale margin, Crenicichla monicae is one of three species in the genus that have smooth scales.”

More than 160 years after Wallace collected it, then lost it—and almost a century after Melin collected it again at Taracuá—the fish has a name. Since Kullander described the fish, researchers have discovered other lost species Melin also collected during his time in the Amazon. In January 2016 Auburn University biologists Milton Tan and Jonathan Armbruster named a new species of suckermouth armored catfish from a single specimen Melin collected in the Rio Negro basin. Hypancistrus phantasma is a ghostly pale, broad-shouldered catfish with a small, underslung mouth and a wedge-shaped body. Phantasma means “phantom.” Like Wallace’s pike cichlid, it waited in a jar for almost a century. Melin and Vilars collected the holotype from the Rio Negro on Feb. 14, 1924. But it hasn’t been seen since.

In 1924 it existed flattened against the riverbed in the deep, swift water. Maybe it exists there still, ghostlike, a phantom fish. Perhaps there are other phantom fish too, suspended in jars in Stockholm and elsewhere. As the years pass the specimens continue to fade, slowly losing their colors and the distinctive patterns and striations that might once have set them apart from the others.

Christopher Kemp is a scientist and the author of Floating Gold: A Natural (and Unnatural) History of Ambergris.

Reprinted with permission from The Lost Species: Great Expeditions in the Collections of Natural History Museums by Christopher Kemp, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2018 by Christopher Kemp. All rights reserved.

References

1. Wallace, A.R. My Life: A Record of Events and Opinion Chapman and Hall, London (1905).

2. Kullander, S.A. & Varella, H.R. Wallace’s pike gets a name after 160 years: A new species of cichlid fish (Teleostei: Cichlidae) from the Upper Rio Negro in Brazil. Copeia 103, 512-519 (2015).