September 1965. Eighty eager young faces are assembled for the first day of orientation at USC School of Cinema. Gene Peterson, head of the camera department, walks onstage in Projection Room 108. His cornflower blue eyes scan the crowd for an unendurable 30 seconds of silence.

“Here’s my advice,” he says to us. “Get out now. You can still get your money back.”

1965 was a low tidemark year in Hollywood—never before (and since) had so few films been produced. The 20-year slide had begun in 1946 with the postwar surges of TV, cars, and suburbs. It was one of the reasons Peterson and other faculty at USC Cinema had become teachers, seeking cover in the leafy groves of academe.

The next day, a third of the class had opted for greener pastures. Those of us who remained did so because, well, that is the question. We were double the previous year’s admission of 40. Why the surge of interest in film at a time when the business was shrinking?

A year later, the faculty identified eight of us as troublemakers, including George Lucas, John Milius, Caleb Deschanel, Matthew Robbins, Randall Kleiser, and me. We were called to sit around a picnic table in the central corral of the cinema department, where we were harangued by our professors for our unwillingness to follow the school rules: No movie should be made more than a quarter mile from the school; only black and white film should be used; no more than 55 minutes of 16mm film should be shot. We were accused of breaking into the mixing theater at 2 a.m. to re-record our films, of not returning equipment on time, of sneaking into the equipment stock room with forged keys to get our hands on precious cameras and sound recorders. All of this was true.

These inventions and revolutions unraveled space and time.

This dressing-down was duplicated across town at UCLA’s School of Theater, Film, and Television, where Francis Ford Coppola and Carroll Ballard had been students a few years earlier; or NYU Film School in New York where Martin Scorsese was a student contemporaneous with us; or Long Beach State where Steven Spielberg would soon be enrolling. None of us had any prior connection to Hollywood.

Once we left school, all of us encountered different forms of The Wall—the barricade that says, “Go away.” The studios were surrounded by literal cement walls, usually about 15 feet high, which broadcast that message clearly. But there were other, invisible walls that we encountered, like the impenetrable Don’t-call-us-we’ll-call-you force field. Ultimately, we film students of the 1960s found our way through, under, or over The Wall and became responsible for films such as Patton, The Godfather trilogy, American Graffiti, The Conversation, Jaws, Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Grease, Taxi Driver, The Black Stallion, Apocalypse Now, Raging Bull, Raiders of the Lost Ark, ET, and many others. Along with Oscars and, for a few of us—present company excepted—great wealth and fame.

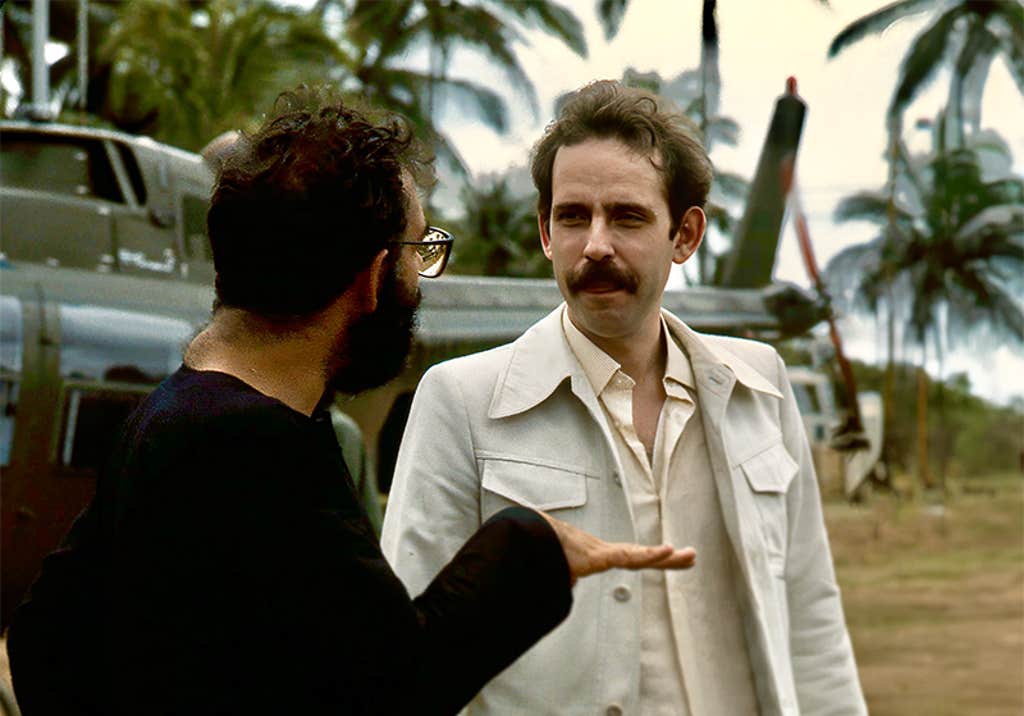

In 2004, nearly 40 years after our student days, I was walking along Kearny Street in San Francisco and came across Francis sitting outside his Café Zoetrope at one of the little tables, trying to write. Since the ’60s, I had worked with Francis as a sound designer and film editor, including on all three Godfather films, The Conversation, and Apocalypse Now. I sat down with him, and we chatted. I was about to start editing Sam Mendes’s Jarhead, and Francis was struggling with a draft of Youth Without Youth, an original screenplay. The blank sheet of paper stared back at him defiantly. “To have come all this way and find myself in exactly the same predicament. What do I want to say and how do I want to say it?”

A tourist bus in the guise of a cable car drove past with its loudspeaker blaring, “Francis Coppola, creator of The Godfather series …” Francis waved amiably at the tourists, who—startled—waved back.

Not long after, I thought about the sudden surge of interest in cinema that so perplexed Peterson in 1965. Looking through the opposite, wide end of the telescope, it is possible that no matter what agency we filmmakers thought we had, we were being pushed along by an invisible cultural wave-force that has only grown more massive over the decades. The United States had three film schools in 1965. There are now 750.

Awe of the Pyramids

Is history made by individuals, or are individuals made by history—carried along by waves of impersonal forces? Near-contemporaries Thomas Carlyle and Karl Marx, in the 1840s and ’50s, offered the two poles of this conundrum. Carlyle felt that “the history of the world is simply the biography of great men,” while Marx professed the irresistible and impersonal forces of evolving class conflict.

Whatever the answer—and it must include some mixture of both—history is streaked with periodic fevers of achievement, which grip and shake entire societies for centuries at a time, and then—as suddenly as they had been gripped—release them transformed.

The frenzy of pyramid building in Egypt—the classic age of the massive stone structures at Giza and Dashur—lasted not quite 200 years, from 2675 to 2500 B.C. During that span of seven generations, seven pyramids were built, taking 20 to 30 years each, directly involving 30,000 workers at the peak months of construction, and hundreds of thousands of secondary supports, at a time when the total population of Egypt was just over 1 million. Twenty million tons of limestone and granite were quarried and transported—the granite floated down the Nile on barges from Aswan, 700 kilometers to the south—using only human muscle power and copper tools. Contrary to stories spun by Herodotus and amplified in the 19th century, no slaves were involved—most workers were farmers idled during the four-month flood season from mid-June to mid-October. They were paid, housed, and fed, and the graffiti they left attest to their enthusiasm.

The pyramids were the first large-scale, all-stone constructions in history, raised to then-unimaginable heights of almost 500 feet, and everyone in Egypt must have been aware and in awe of what they were creating. The Nile Valley at that time was one of the only places in the world with an agricultural surplus capable of supporting such an effort. It’s arguable that the collective accomplishment of pyramid construction, along with the innovative social organization necessary, was the forge that finally and firmly cemented the two kingdoms of Egypt into one of the first, and longest-lasting, nation-states in history.

Visitors to Giza feel a fragment of this awe today, which my wife Aggie and I were fortunate to experience in 1980 when I was writing a screenplay about archaeology. The Great Pyramid is, objectively, “just” a pile of stones, but it is steeper than any pile you would ever see in the natural world. It inclines at 52 degrees, 7 degrees steeper than the maximum angle of repose. No simple pile of aggregate—stone, sand, or gravel—is stable at greater than 45 degrees. Their stability was due to their precise construction and internal buttressing: interior walls of stones leaning against each other at 75 degrees.

Structurally speaking, the pyramids are already collapsed, so to speak, and have nowhere farther to go. In that engineering sense, the pyramids are supernatural, and this is something you feel, viscerally, standing in front of them. They are magnificent and unsettling at the same time. If we feel this today, how much stronger must that have been 4,600 years ago when there was no comparable human achievement anywhere on Earth?

The same feelings arise again in the frenzy of 350 years of cathedral-building in Europe, from the middle of the 12th century to the 16th century. Well over 100 huge gothic cathedrals were built for the bishops of Europe, along with many thousands of churches. The cathedrals boasted immense interior spaces filled with light streaming through magnificent stained-glass windows, and the seemingly unsupported pointed arches floated high above the heads of the congregation. One of these cathedrals, at Lincoln in England, exceeded the Great Pyramid in height by about 46 feet—after almost 4,000 years it was the first time the Pyramid’s height had been surpassed.

Like the construction of the pyramids, these three centuries of cathedral-building were instrumental in forging a unity out of the multiplicity of Europe, with master-architects and craftsmen ceaselessly criss-crossing borders to spread their cultural and engineering skill set from country to country. Estimates are that around 20 percent of all economic activity during this period was dedicated to the construction of cathedrals and churches throughout Europe.

These examples (out of hundreds from world history) reveal how a society can be suddenly rocked by breakthrough developments, which flow through the entire population in a dozen generations or so, flooding society with their transformative effects, before they dissipate, sometimes suddenly, leaving a reimagined, transformed society in their wake.

Are we embroiled in one of these waves now, at the beginning of the 21st century? Have we been for some time?

Film Takes Flight

When I was 15, I read The Immense Journey by Loren Eiseley, who has had a great influence on my thinking ever since. “How Flowers Changed the World,” one of the essays in the book, taught me that evolution often has the uncanny ability to “Houdini” itself out of seemingly intractable puzzles, turning the attacks of animals on plants into actions that spread pollen and seeds in directed vectors. The plants have co-opted their enemies, and no longer needed to rely on the mindless whims of wind and water for propagation.

In 1970, Eiseley wrote The Invisible Pyramid. It was his attempt to deal with the phenomenological effects of powered air and space travel over his lifetime. How had this epochal achievement transformed society, expanding not only our sense of reality but also the limits of what was possible? In Eiseley’s opinion, it was as transformational as the construction of the Egyptian pyramids, but a transformation so pervasive and universal as to be invisible—not localizable to a single set of spatial coordinates.

Eiseley was born in 1907, four years after the Wright brothers lifted off at Kitty Hawk in 1903. He saw Halley’s comet when he was 3 and lived to see men on the moon in 1969, but not Halley’s return in 1986.

The year of Kitty Hawk was also, serendipitously, the year of Edwin Porter’s The Great Train Robbery—the first massively popular film to use editing to tell a complex story. And edited film, along with powered flight, are the two miraculous inventions whose reach and scope would come to define the 20th century in all its glory and horror.

Thanks to film editing, long and complex films like D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation could be planned, broken down into individual shots and scenes, and photographed in the most efficient order. They could be re-knit into a convincing three-dimensional mosaic—two dimensions of space and one of time—to represent, in symphonic or novelistic terms, the full breadth of the human comedy or tragedy. Editing freed cinema from the binding gravitational pull of the single shot, and allowed it to take off, in both a creative and a logistical sense. It is a poetic coincidence that those two symbols of the previous century, edited film and powered flight, have almost simultaneous birthdays.

Yet film and flight are perhaps part of an even larger wave, one of those world-encompassing eruptions of creativity, which began suddenly in the 1830s and is ongoing 200 years later.

It was in 1833 that Belgian physicist and mathematician Joseph Plateau invented a device he called the phenakistoscope, a word derived from the Greek words phenakistes, meaning imposter, and skopein, meaning to look.

Plateau’s invention was a rotating disk with slits around its circumference like the hours of a clock and a series of drawings on the opposite side from the viewer—usually of a human being in action (walking, jumping)—each drawing lining up with one of the slits.

To operate it, you would hold the disk between your eye and a mirror and then spin the disk while looking through the slits. Amazingly, the images would animate in a repeating loop, exactly like today’s GIFs.

The phenakistoscope was an instant popular success, releasing a surge of dammed-up creativity, thanks to the fabulous nature of the drawings created for it—rats or snakes surging from the center of the disc to the circumference!—as well as an improved technology, the zoetrope, invented in 1834 by British mathematician William Horner.

Horner’s invention was a rotating drum with slits and a strip of drawings on the inside, and did not require a mirror to view the animation. You could spin the drum in one direction and young girls would be transformed into old crones; spinning in the other direction, crones turned back into young girls. Both Plateau’s and Horner’s inventions were so simple in construction that they could have been invented thousands of years earlier by the ancient Egyptians.

Yet in that phenakistoscopic year, 1833, if you wanted to move yourself, information, or material, the speeds available to you were roughly the same as they were four millennia earlier. You likely walked, ran, galloped on a horse, rode in a horse-drawn carriage, sailed on a ship blown by the wind or rowed by ranks of galley slaves. Messages could be sent by courier, carrier pigeon, semaphore, mirrors, smoke signals, or drums. The time-and-space matrix of human civilization had been virtually frozen ever since the almost-simultaneous invention of writing and the wheel in Mesopotamia around 3500 B.C.

The cinematic cut is where the chisel of the splice cleaves the stone of time.

But five years after the phenakistoscope, in 1838, three other time-and-space-conquering inventions burst upon the world: electrical telegraphy, steam power for ships and railroads, and photography.

Samuel Morse demonstrated the potential of telegraphy to Congress in 1838. Its speed was virtually instantaneous: Electric dots and dashes of abstracted language were sent skimming along wires at the speed of light.

In 1838, London and Birmingham were connected by steam railroad—the world’s first long-distance passenger rail service. It moved at 20 miles an hour, four times faster than horse-drawn carriages. Double that speed was achieved by 1845, and double again—80 miles an hour—by 1850, when steel rails replaced wrought iron.

In that same year, 1838, the first steamship passenger service began between England and the U.S., established by Isambard Brunel’s Great Western, the largest ship in the world at the time, which took only 15 days to cross the Atlantic, four times faster than the average for sailing ships.

Brunel’s Great Eastern, launched in 1858, was bigger and faster still—her size and capacity were not surpassed until 1913. She could carry 4,000 passengers, and in 1866 she laid the first telegraphic cable across the Atlantic, merging steam and electricity. London could now communicate with New York at the speed of light.

Unraveling Space and Time

The 1830s also saw the invention and commercial application of photography, a technology that freezes time. And freezing time is the first step to controlling it. The very first photograph was taken in 1827: Joseph Niépce’s view from his attic window. But it required nine hours of exposure to register the blurry image, more of a slushy than a frozen moment, but a historical one, nonetheless.

By 1838, Louis Daguerre had perfected his daguerreotype which increased clarity by several orders of magnitude and reduced the photographic exposure time to 90 seconds. By 1845, that had shrunk to a second or two, and by the end of the 19th century photographs were being snapped at a 50th of a second.

Information moving at the speed of light, travel times cut by 75 to 90 percent, photographically frozen milliseconds—the apparently solid matrix of time and space that humanity had taken for granted was rapidly distorting and dissolving in a foretaste of Einstein’s relativity. But things would only accelerate: Edison’s inventions of sound recording (freezing waves of sound in mid-flight), practical electric light, and motion photography were to come in the last quarter of the century, along with Bell’s telephone, Marconi’s radio, Daimler’s automobile, and Tesla’s AC electrical energy.

Before we had time to digest any of these seemingly miraculous, Earth-shaking inventions, the 20th century rushed on with powered flight, Max Planck’s quantization of physics, and continued breathlessly with Einstein’s theories of relativity, the mass production of automobiles, a World War, radio networks, sound and color film, another World War, radar, sonar, computers, the atomic bomb, television, rocketry, jet planes, transistors, atomic energy, satellites in orbit, lasers, men on the moon, the internet, cell phones, and the discovery of exoplanets. The 21st century has so far given us the decoding of DNA, smart phones, social networking, dancing robots, streaming services, artificial intelligence, and … as kids whine on long drives with their parents, “Are we there yet?” As my father would answer, much to my annoyance, “Probably not!”

If at first your idea is not absurd, then there is no hope for it.

What united all those inventions and revolutions, since the first stirrings in the 1820s and ’30s, was their ability, directly or indirectly, to unravel humanity’s previously fixed concepts of space and time. For the past two centuries, we have been totally and enthusiastically dedicated to shrinking or abolishing space and chopping or wrinkling the fabric of time—no matter what the cost or challenge involved.

Cinema not only participates fully in this unraveling process, it is one of the main drivers. Photography had made it possible to freeze time, but as a result, photographs themselves became manipulatable, leading inevitably to the invention of motion photography. And once that had been achieved, motion itself became magically malleable, either by reversing it, speeding it up, slowing it down, or interrupting and reorganizing it with editing. The cinematic cut is where the chisel of the splice cleaves the stone of time.

In his 1986 book, Sculpting in Time, Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky wrote that “for the first time in the history of the arts, in the history of culture, man found the means to take an impression of time. And simultaneously the possibility of reproducing that time on screen as often as he wanted, to repeat it and go back to it. He acquired a matrix for actual time. Once seen and recorded, time could now be preserved in metal boxes, theoretically forever.”

From the viewpoint of someone from the 18th century, all this would seem miraculous and absurd. But as Einstein would remark: “If at first your idea is not absurd, then there is no hope for it.”

In 1895 one of the inventors of motion pictures, William K.L. Dickson, made predictions, unsupported by any of the facts at the time, about a glorious future for cinema—what he called the kinetograph—involving sound, color, and even trips to other planets.

What is the future of the kinetograph? Ask rather from what conceivable phase of the future it can be debarred! The rich strain of an orchestra, issuing from a concealed phonograph will herald the impending drama: The voices will be full of mirth, pathos, command—every subtle intonation which makes up the sum of vocalism.

Some tempestuous ocean scene, quickened with the turbulent anguish of the unresting sea; the clang of arms, the sharp discharge of artillery, the roll of thunder, the sound of Andalusian serenades—all these effects of sight and sound will be embraced in the kinetoscopic drama.

Not only our own resources, but those of the entire world will be at our disposal. We may even anticipate the time when the latest doings on Mars, Saturn, and Venus will be recorded by enterprising kinetographic reporters.

Dickson wrote this before human beings had even invented powered flight, much less space travel. But his prediction did come true in 2012, 117 years later, when Curiosity Rover sent back the first motion pictures from Mars.

Invisible Pyramid

Viewed from this wide end of the telescope, then, it appears we student filmmakers in 1965 were simply being carried like foam on the waves of history, as all of us may be, irrespective of what we thought we might be doing—agents of the great unraveling of time and space.

Did we have free will? Perhaps. There is a difference between a human being and a fleck of foam, isn’t there? But it is an eternally oscillating puzzle. What is the cause and what is the effect? Who is in control and who controls the controller? As Isaac Bashevis Singer wrote, neatly capturing the paradox, “You must believe in free will—you have no other choice.”

So, what will this furious conquest of space and time ultimately achieve? Why are we so feverishly dedicated to achieving it? At least with the pyramids there was a plan, and there must have been a proclamation from the Pharaoh and his priests at the temples, to which the population of Egypt responded.

But the dissolution of space and time was not proclaimed, officially, by anyone. It simply coalesced, grew, and gathered unstoppable momentum as everyone (aside from naysayers like Henry David Thoreau) seemed enthusiastic about what it offered: the realization of formerly unachievable dreams, such as instant communication across vast distances, flight, and the freezing or reversal of cinematic time.

In The Invisible Pyramid, Eiseley speculated, with trepidation, “that perhaps man has reached an evolutionary plateau, and to advance beyond he must either intimately associate himself with machines in a new way or give over to exosomatic evolution and transfer himself and his personality to the machine, and thus escape, or nearly escape, the mortality of the body.”

This is beginning to happen. People in labs can now control the movement of screen cursors with their thoughts alone, thanks to brain implants. At the same time, virtual reality goggles and artificial intelligence are making alarming leaps. Some kind of a fusion of virtual reality, artificial intelligence, and brain implants is looming, raising the specter of Ray Kurzweil’s “Singularity,” the biological meshing of human beings and intelligent machines. Time and space themselves are being revealed as fundamental illusions by physicists.

What will this furious conquest of space and time ultimately achieve?

Maybe the invisible pyramid has been acclimatizing us, over multiple generations, to survive the shock when the last threads of the time-space safety net are finally pulled out from under our feet.

So, will some future point in the 21st century mark the end of our human experience of time and space, bringing to a climactic end these two centuries of feverish achievement? As the unified nation-state lay on the other side of the pyramid age, what awaits us? It is hard to imagine, from our perspective today, still caught in the froth of such furious activity, what would lie on the other side of the Singularity. But the invisible pyramid’s ultimate purpose will only be fully revealed when the wave recedes. Then, perhaps, its true purpose will finally become visible.

A Hopeful Fever Dream

Today, we look at creations like the pyramids not only in awe of the buildings themselves, marvels of architecture, but also in astonishment at how they were constructed: human muscle and copper tools—no wheels or horses were involved.

Will our descendants 4,000 years from now—and I pray that there are some—screen our films and appreciate what we accomplished with our paltry tools as we struggled to forge insubstantial dreams out of the iron of recalcitrant reality? A struggle Jean Cocteau described in 1946, during the making of his Beauty and the Beast.

Try to hold the threads of this enormous and delicate mechanism in your hands; subdue all the dust, independent wills, ingenious disorder; call for action, interrupt it (because of a broken thread), resume, and never lose hold of the big picture.

Perhaps by then our descendants will have discovered some new forces of nature that would be as powerful and as mysterious to us as electromagnetism and nuclear energy would have been to the ancient Egyptians.

And rather than light, our far-distant children will take our films and beam this new energy through the images, seeing not the pictures themselves, but a dynamic multidimensional pattern—endlessly fascinating because its swirling beauty will somehow reveal to them the intricate and powerful interplay of all the influences and personalities that improbably came together, sometimes in harmony, sometimes in conflict, to shepherd the film—Cocteau’s “enormous and delicate mechanism”—along its path from dream to reality.

“How did they do it,” they will wonder, shaking their heads, “when they didn’t know about χ or υ, or even ζ ? Incredible!”

Back here in the present, we know that every film we make is the complex product of myriad influences and personalities, ranging from the accidentally trivial to ingenious disorder, the serendipitously coincidental to the existentially profound. But the true sources and detailed interplay of those internal organs of creativity remain mostly hidden, even from us filmmakers, as they move and mingle mysteriously under the glossy skin of the film. ![]()