Pope Francis may be the first pontiff in Roman Catholic history to embrace the voice of the modern pundit. In 2015, he wrote an encyclical on climate change, “Laudato Si’,” which the New Yorker described as a “blistering indictment of the human failure to care for Earth” and a “poignant description of the momentous choice now confronting every government, corporation, and person on the planet.” So perhaps it was just a matter of time before the head of the Roman Catholic Church pivoted from God to another global problem—fake news.

The scale and danger of global disinformation may not be as grand and existential as the prospect of a warming planet, but that didn’t stop the pope from recently penning what the New York Times called “a major document about the phenomenon of fake news.” In it, he wrote, “Untrue stories can spread so quickly that even authoritative denials fail to contain the damage.”

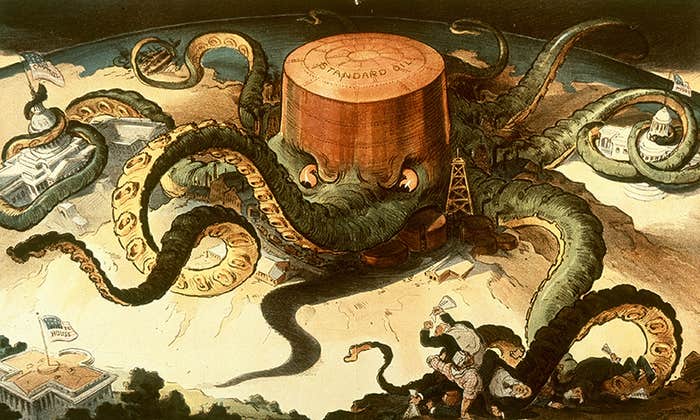

The Catholic Church amassed much of its vast following and fortune, still held to this day, on the generation of fear.

One definition of “irony,” according to the Oxford Dictionary, is that it is a “literary technique, originally used in Greek tragedy, by which the full significance of a character’s words or actions is clear to the audience or reader although unknown to the character.” This is the sense of irony with which I read the Times report on the Pope’s document, which revealed that the first form of fake news, to the Pope’s mind, was recorded in the Bible: Satan’s temptation of Eve to eat the forbidden fruit from the tree of knowledge. Satan told her that if she had a bite she’d know of good and evil, as God does, and wouldn’t “surely die,” as God had earlier threatened. But Eve didn’t die on the day she ate the fruit. So wouldn’t it be God, not Satan, who spread fake news first?

The Pope writes, “Fake news is a sign of intolerant and hypersensitive attitudes, and leads only to the spread of arrogance and hatred. That is the end result of untruth.” True enough. And a message that should be broadcast far and wide. But it’s also hard to ignore the irony of the leader of the Catholic religion decrying intolerant and hypersensitive attitudes, to which Catholic dogma has contributed for centuries.

Classicist Kyle Harper, in his new book, The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire, shows Christianity took root and spread on what could be called fake news. After Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity, Harper writes, he…

severed the lifeblood of funding for the old gods, surreptitiously looted the temples, and put blood sacrifices on their way to extinction. At the apex of the social pyramid, the emperor’s tastes set a tone, even in matters so intimate and inscrutable as the worship of the gods. Constantine was the empire’s patron in chief, and his favoritism rippled outward in expanding circles of influence. For Christianity, Constantine’s uncanny choice [in converting to the faith] was the watershed, the moment of irreversible acceleration.

The Catholic Church also amassed much of its vast following and fortune, still held to this day, on the generation of fear. “Christianity is an eschatological faith,” Harper writes, and “apocalyptic notes run like a constant background music across the history of the church.” The “end times” tune, during the bubonic plague of the 6th and 7th centuries, proved lucrative, because “the plague was a last chance to turn from sin,” Harper writes, and conveniently for the church, “no sin weighed more heavily on the antique heart than greed.”

In Egypt, Harper points out, “we happen to see that the plague triggered an instantaneous effusion of pious giving.” The writings of John of Ephesus, a church leader in the Middle Ages who tortured heathens, had made clear that the “mass-mortality was a wake-up call to the survivors, sent as a courtesy warning in advance of the great judgment to come,” Harper writes.

In the end, what fake news breeds, like religion, is unnecessary uncertainty, a pernicious kind of epistemological gaslighting. But unlike religion, it’s virtually all online. Not long before “fake news” became news, Nautilus asked the primatologist and neuroendocrinologist Robert Sapolsky whether the Internet is making us ill. He seems to anticipate the phenomenon in response: “We’re inundated with nonsense decisions, nonsense information. That’s not stress-reducing. That’s stressful.”

Brian Gallagher is the editor of Facts So Romantic, the Nautilus blog. Follow him on Twitter @brianga11agher.