“The date of diagnosis? Do you mean a specific day?” The well-mannered older man with advanced lung cancer sighs, pauses, takes off his glasses, strokes through his gray, cared-for beard, and looks at me as if trying to decide whether or not I will be able to follow his thoughts.

“Kafkaesque! That’s what it is, Kafkaesque.” He was obviously pleased with his exclamation, which to be honest, did not help me much. Looking in my eyes, he felt my uncertainty, sighed again, not in an unfriendly or arrogant manner, but perhaps with a bit of disappointment that I was unable to share his moment of delight at finding a fitting expression.

Few tasks are more challenging than breaking bad news, especially if a patient seems reluctant to engage in conversation. Any question posed by a patient provides an opportunity to get started. What made this situation unusual is that the question referred only to the time of diagnosis. This lovable bibliophilic man introduced me to the particular atmosphere in Kafka’s work: “…instances in which bureaucracies overpower people, often in a surreal, nightmarish milieu which evokes feelings of senselessness, disorientation, and helplessness.”

The patient continued, “You understand that the many tests and the elusive information of the recent weeks remind me of Franz Kafka’s words in his famous work Der Prozess, meaning both trial and process.” “The verdict does not come suddenly, proceedings continue until a verdict is reached gradually.”

Another way to translate the sentence from German would be: “The verdict does not come suddenly, the process gradually transforms into the verdict.”

The patient went on. “First there was this cough, not unusual for me, but a bit more pronounced than in recent months. One day I had to consult my general physician after I had tripped and broken a rib. I think my process/trial started as my first x-ray touched the backlight in my GP’s office.

“A ‘shadow’ was visible. A CT scan was ordered the same week. A ‘mass’ is described—in my right lower lung.

“My physician advised me not to think too much before cytology results were available; samples would be taken the next day. Of course, I was absorbed by frightening scenarios, including a painful death. How could I avoid these thoughts after losing friends whose processes/trials started with shadows and masses and culminated in the verdict of a death sentence? My trial had begun—consuming my days and my thoughts.”

“…without having done anything wrong he was arrested one fine morning.”

“Another doctor tried to move my trial along by sampling some of these cells through a tube which he inserted into my airways in order to prove or exclude a neoplasm. I am being taught new technical terms on a daily basis. Two days later I was informed of the results: No malignant cells.

“So did my head stop spinning now? Was this trial over? Am I being released? I am not sure that I felt relief.

“Somehow, this doctor did not see it end here: ‘Sometimes, cytology is not reliable enough. In order to proceed you need a biopsy.’ This is arranged for me for the next day.”

“It is not necessary to accept everything as true, one must only accept it as necessary.”

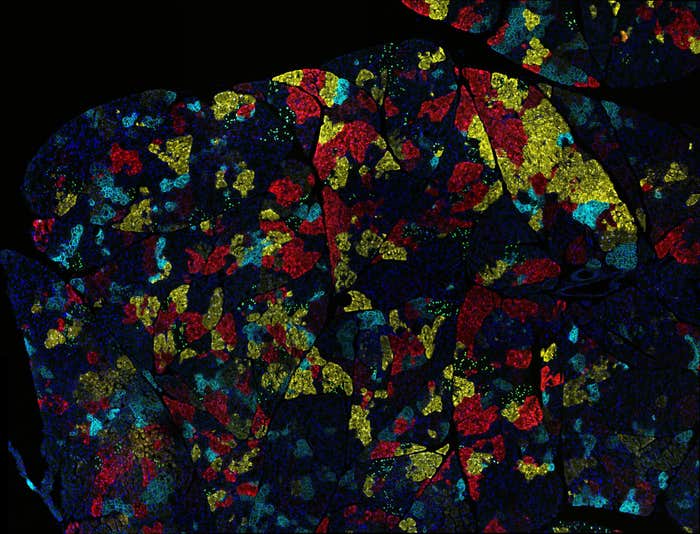

“It was the cancer tissue under the pathologist’s microscope, which irrevocably established my diagnosis, my verdict. Relief—that was my first emotion,” the patient said with watery eyes. “Not that I did not understand the impact of this serious disease, but it was a verdict. Finally!

“I was transferred to this hospital and I realize that my process/trial continues here. The hospital’s staff explains that as a patient I am expected to be patient; that several experts are working on my case, ensuring that my process is following its predefined course.

“Before retirement I had been smoking for many years, and feelings of guilt surface from time to time. However, I am not thinking clearly and the last week’s ordeal left me an emotional cripple—unable to feel grief or joy. Surely, the doctors here know how to proceed, but like in Kafka’s Trial, nobody addresses me directly.”3

“‘We’re all human beings here, one like the other.’

“‘That is true,’ said the priest. ‘But that is how the guilty speak.’

“‘Do you presume I’m guilty, too?’ asked K.

“‘I make no presumptions about you,’ said the priest.

“‘I thank you for that,’ said K. ‘But everyone else involved in these proceedings has something against me and presumes I’m guilty. They even influence those who aren’t involved. My position gets harder all the time.’

“‘You don’t understand the facts,’ said the priest. ‘The verdict does not come suddenly, proceedings continue until a verdict is reached gradually.’

“‘I see,’ said K., lowering his head.”

The diagnosis of cancer is a serious and often traumatizing event, which some patients report as the most challenging time during their illness experience. The trauma of cancer diagnosis is not only not mitigated but aggravated by uncaring physicians who fail to acknowledge how difficult and daunting the transition from being a healthy person to being a patient with cancer must be. Kafkaesque communication by physicians and technicians might turn hospitals into impersonal bureaucracies, with physician-persons representing the remedy.

The nightmarish process with profound existential dread exceeded the coping capacity of our protagonist, who complained about nightmares and the loss of coherence. He may not have had a full-blown post-traumatic stress disorder, but merely—and quite conceivably—a high level of distress.

A distant and formal way of dealing with patients may exert its toll on the oncologists’ well-being as well, because the inability to address patients’ worries, be it a result of lack of time, courage, or compassion, diminishes physicians to elements of a sterile process, rendering them vulnerable to burnout—symptoms of which are reported by nearly half of US physicians.

Assessing and understanding the patient’s narrative to put the process of diagnosis into perspective may prove invaluable to the patient, the physician, and their relationship. Avoiding Kafkaesque communication (possibly after familiarizing oneself with it after reading The Trial) might potentially comfort desperate patients and enrich the work of emotionally distant oncologists, thereby reducing distress among patients and burnout among oncologists. The importance of understanding the patient’s narrative has been elegantly expressed by the Danish existentialist philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855): “If one is truly to succeed in leading a person to a specific place, one must first and foremost take care to find him where he is and begin there. This is the secret in the entire art of helping.”

Image credit: Rafael Edwards / Flickr

Reprinted from the Journal of Clinical Oncology