This article is part of Nautilus’ month-long exploration of the science and art of time. Read the introduction here.

How is composing music of a given meter similar to painting flowing water? In this conversation between the composer and musician Philip Glass and the painter Fredericka Foster, two artists set out to tackle this question, before flowing into questions of memory, physics, and death.

Glass and Foster met in the late 1990s through their mutual interest in Buddhism. They shared a teacher, Gelek Rimpoche, and attended yearly meditation retreats together in Ann Arbor, Michigan. When I invited them to have a conversation about time, they both responded with great interest and curiosity. How better to reflect, they said, on a decades-long relationship that had been sparked by Buddhist teachings and strengthened by a mutual artistic admiration?

Getting them together was less easy. Glass was traveling in Europe, while Foster was in Seattle. So we recorded a telephone conversation, transcribed it, then recorded a second conversation to fill in the gaps. In a way, the resulting dialogue between the two artists—their first formal collaboration—is informed by its own distortions of time and space.

After Glass returned to New York, I got a chance to see him perform a piece at Carnegie Hall that was introduced more than 30 years ago. It was recognizable as a Glass signature, but at the same time it was something different, even better than the original. As I was listening to the piece, I was reminded of what my collaborator, Lee Smolin, wrote in his introduction to our project on time:

“In the new view of time, time is essential, and irreversible because it generates genuine novelty.”

Time had given a genuine novelty to Glass’ performance of an old piece. I expect it will do the same years from now, when two old friends reread their conversation on an ageless topic.

Fredericka Foster: Your entire life in music has been about time. I remember you saying that the way you were finally able to score Ravi Shankar’s music was to remove the bars—that allowed every single note to have the same value, and that changed your sense of musical time.

Philip Glass: There are many strange things about music and time. When I’m on a tour with the dance company we work in a different-sized theater every night. The first thing the dance company does when we arrive is to measure the stage. They have to reset the dance to fit that stage. So you also have to reset the time of the music: In a larger theater, you must play slower. In a smaller theater, you have to play faster. The relation of time and space in music is dynamic. I have a range of speed in mind. If the players don’t pay attention to that, it will look really funny. You can see the stage fill up with dancers because they are playing at the wrong speed.

FF: I understand that variability. I usually paint water. Watching water move is a time-honored way of moving into the present moment. My goal is to feel the water move in the painting, but water has rules, and I have to pay attention to motion in establishing the composition. Water is defined by time: the length of time it takes for a wave to pass a set point. At around a second, you have a ripple; over 10 seconds, a swell, and in between a wave. Once I get the composition down, I can begin to pay attention to the rhythm of the painting. I put on music (for example, your Satyagraha) and enter into a dance with the painting, changing the composition to exaggerate the rhythm. Time disappears. I become a verb, seeing, painting. That time cannot be measured. With this kind of focused attention, time has no boundaries. That’s the kind of time you find in love, in creativity, in the life of the spirit, the kind of time I live for.

PG: When I look at a painting, time always seems to be in the present. In music, things happen in measured time. When a painter looks at a canvas, time is irrelevant. I was visiting Jasper Johns once, looking at one of his number paintings from 10 years before. He said, “I am still working on that painting.” When I look at your paintings, for you a day of work may go by fast or slow, but the painting is the painting, and looking, I can jump in and get to zero time easily.

FF: As creative artists, we are involved with novelty, and that seems to be one of time’s gifts. You have managed to keep your music new.

PG: Sometimes when I sit down to write a new symphony, I say, “wait, I did that already,” and then I throw it away. At least half of the time I’m able to do new pieces. I’m suspicious of pieces that sound like something I did before. It’s the easy way out. I change as much as I can. I’m playing a piece at Carnegie Hall that I haven’t played in 49 years. I have to rehearse it and I find I am playing it differently than I played it initially. The 31-year-old Philip who played that piece is gone. If that Philip had been able to hear the piece as I do today, I think it would have freaked him out.

FF: Does time collapse for you when you’re playing an early piece?

PG: I do it for fun and for the shock of recognizing how things have changed. I ask myself, “Who was that guy who wrote that piece and where did he go?” When I see this guy with a tee shirt and jeans and long hair in a photograph, I think, “Who was that?”

FF: I have the same reaction to my young self: Who was that woman? Time has changed me along with the conditions of my life. I feel creative when I free myself from my conditioning—all those repetitions over time.

PG: That’s right. “Nova” is the root of the word novelty. Newness. How do I continue to change? What is the engine of change? It can be a lot of things. It’s like keeping the ball in the air.

FF: I can hear in both our voices that we’ve been able to keep the child in our being alive, that tremendous curiosity. So many people have lost that in the sorrows of life. We’re lucky.

PG: I actually have real boys 14 and 16, and we look at each other. They look at me and see a guy who is 80, and I look at them and see myself as a 16-year-old. I then go back to the piano and translate a piece from 49 years ago. I had a strange conversation with one of my children. At the end of the summer, I asked “how was the summer?” Marlowe said, “it was fine daddy, but it went by so fast.” When I was a kid at camp, the summers seemed to go on forever. What if both of us were right? Is time passing by faster now than it was 65 years ago?

FF: Now we are in the realm of physics.

PG: Yes, so then I was reflecting on the universe expanding. We know that it is and can measure it, by the way time is operating, or by the way we see a star exploding far away. For various reasons, when a physicist tells me that the universe is expanding, I say “ok, let’s go back to the dance floor.” The dance floor is getting bigger, what does that mean? It means that time has to slow down.

FF: And that is exactly what the physicists tell us is happening.

PG: Yes, but when I talk to my son Marlowe and he says the summer went by very fast, and in my childhood the summer went by really slow—what if it’s really true that time is actually speeding up? One can say, oh, you’re just imagining it; of course I’m imagining it, but what if it’s really happening? In other words, for the universe to keep expanding, maybe time has to go faster too, in order to keep up.

FF: It certainly feels that way.

PG: Many of us have that feeling. Yesterday I was 20. Where did all the years go? “How can it go by so fast,” we say. But what if time is actually speeding up? If everything is changing at the same speed, there is no way to measure it. The summer of 1947 went by very slowly for me, and this summer flew by for both Marlowe and me. What I suggest is that these are not subjective, but rather objective experiences. It’s also a little terrifying. What if 1,000 years from now, a life span felt like it was only a few days?

FF: But right now, by expanding ourselves with the Internet, we have added new brainpower, reducing the amount of time we take to learn something. Time is speeding up in a real way. Younger people’s sense of time is completely different than mine; they have been working on screen time since they were tiny. Perhaps the reason why summer went by so fast for your son is that he has never experienced the slowdown in time, or boredom.

PG: And what about the insects or birds who live for only a few days? Flies can measure their lives in hours, which seems pathetically short.

FF: Yes, but perhaps they aren’t aware of that. Perhaps they’re only involved in lived experience, and don’t actually think about time the way we’re able to do as time-bound creatures with self-awareness.

PG: I’m thinking now about the opposite of the mind being in the body. My intuition tells me that at the moment that your mind separates from the body, experientially speaking, time has stopped. We have heard that at the moment of death, we receive the gift of timelessness. Some people believe that you move into a different body, others say they are afraid of dying because there is nothing there. The real issue is that there is no time there. That doesn’t mean that your mind has stopped, it means that your mind is no longer functioning in the realm of time. We wouldn’t be able to experience time without the body.

FF: Some of the ways we think of time make no sense, measuring our lives as we age by “the amount of time we have left.” We have never known that. You have to stay grounded in the moment. And yet as artists, we can see culture giving us connection with people over thousands of years. When I see a handprint from the Southwest that an artist placed there when the rock was still clay, it is as though I am getting a hello from the past.

PG: In a cave in France, bones of birds were found from 70 to 80 thousand years ago, and the bones turned out to be musical instruments. People had hollowed out the bones to make whistles.

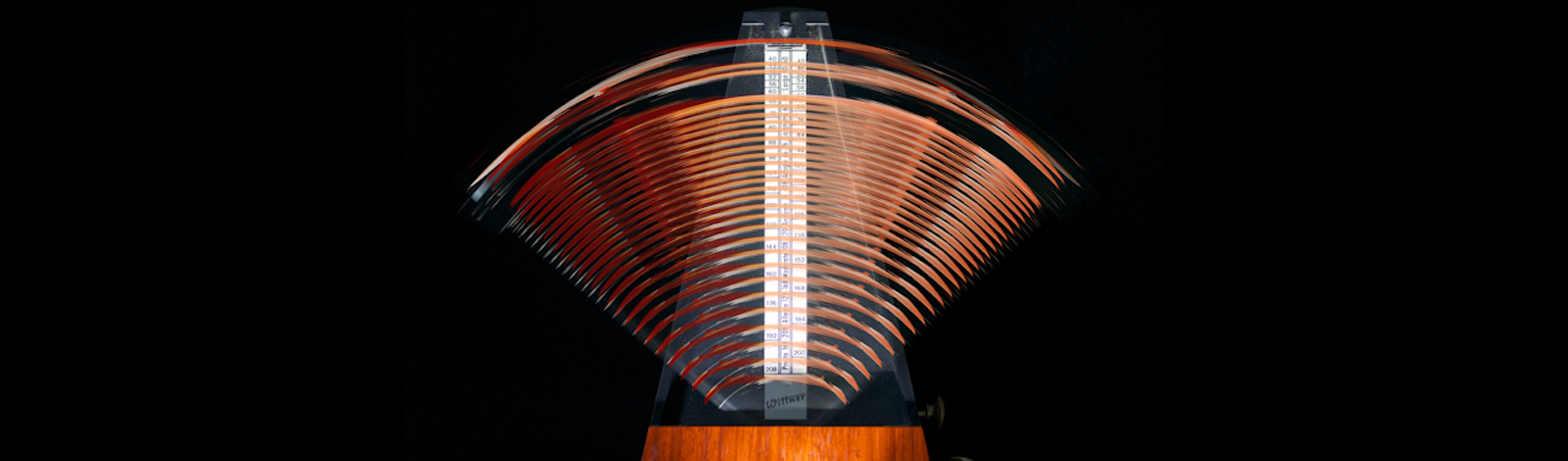

FF: And surely percussion instruments also: a time-honored way to unite the body and mind. Rhythm also unites me with my painting. When I listen to your music, your sense of rhythm permeates all that I do. That rhythm, that flexible metronomic time is so important because it also carries the melody; something that transcends just that moment.

PG: So when we talk about timelessness, what are we talking about? Are we saying we have no way of measuring time? Are we measuring the shadow of time? The shadow of a person is certainly not the person. It’s challenging to come up with a coherent picture of time when you start looking at it in all these different ways. We have different ways to stop time: We can stop time through a meditative process; through a leaving-the-body process; or considering light as it travels through a trillion uncountable years. But to us, time is absolutely real. It can be confusing. Like when you’re a musician playing with a dance company.

Beth Jacobs is the managing partner of Excellentia Global Partners, a global life sciences investment bank.

Fredericka Foster is an artist who works in oil painting and photography.

Philip Glass is a composer and musician.