Watching the short film Planktonium, the latest from Dutch filmmaker Jan van IJken, can feel like a meditation. The miniscule lifeforms he films under microscope mesmerize. Planktonium feels imbued with the spirit, you might say, of another Dutchman, one from the 17th century, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, the father of microbiology. “Leeuwenhoek delighted most in the forms, interactions, and behavior of his little ‘animalcules,’ which inhabited a previously unimagined microcosmos,” the British biochemist Nick Lane wrote of Leeuwenhoek not long ago. Van IJken shares this delight. “The film,” he writes on his website, “is a journey into an unknown universe inhabited by alien-like creatures.”

Planktonium isn’t van IJken’s first film to feature the glories of nature. Becoming, a short film from 2018 with over a million views on Vimeo, showcases the genesis of animal life. A 2012 short film, Facing Animals, offers a glimpse into the complexity of our relationship to other creatures. About the creatures of Planktonium, van IJken told Nautilus recently, “They’re all collected in the Netherlands, a lot of them near my place, but also from the North Sea, which is not far from here, 15 minutes by car. But also in the dunes, small lakes, small puddles, small rivers, everywhere.” It’s not rare for him to find something surprising. “For example,” he says, “in the dunes, you have two small waters next to each other. One is filled with dinoflagellates, the other with ciliates. They all have their own biotope. It’s really amazing.”

We caught up with van IJken to hear how he put his latest film together, starting with how he picked up an interest in shooting plankton.

How did you get started filming these microscopic creatures?

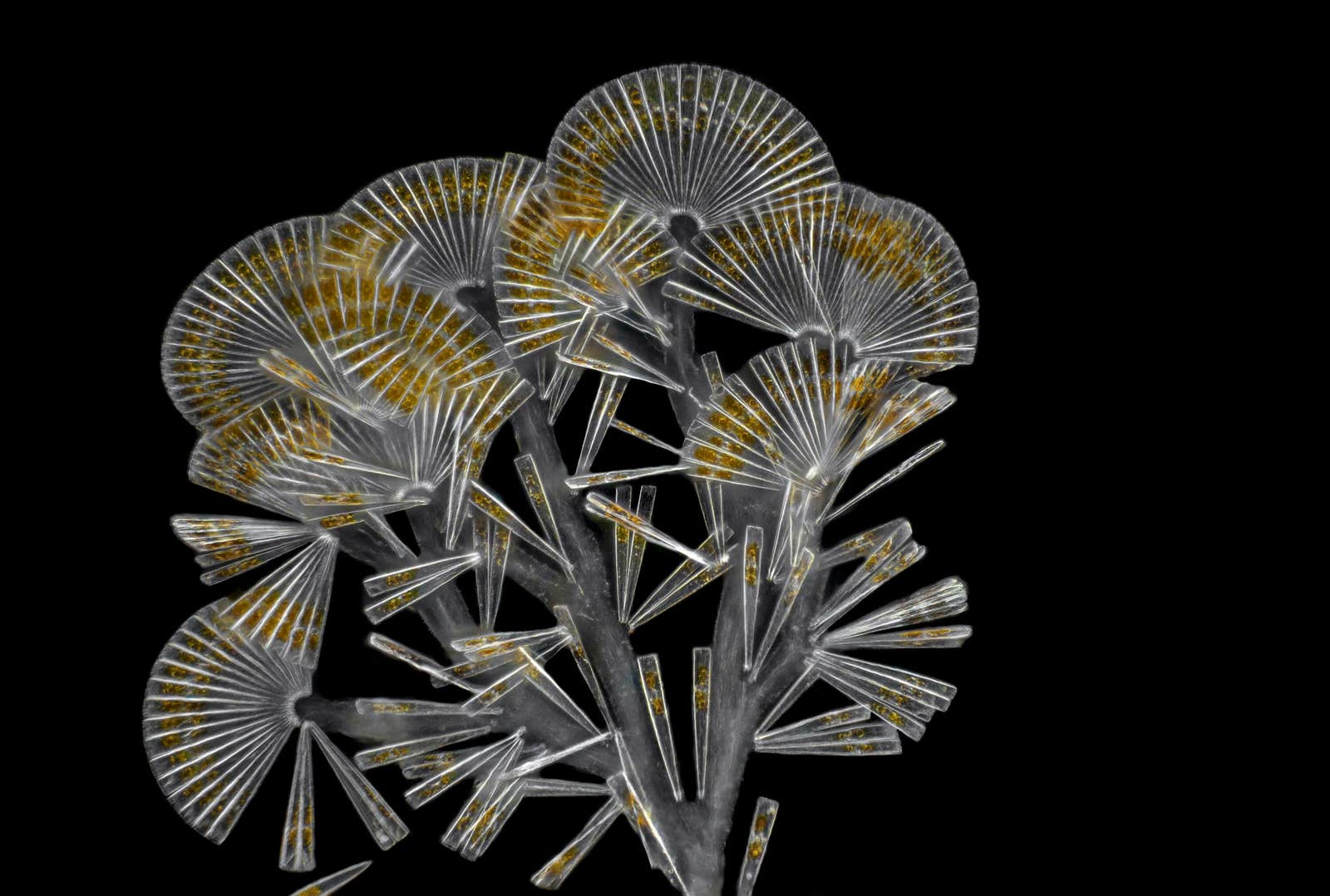

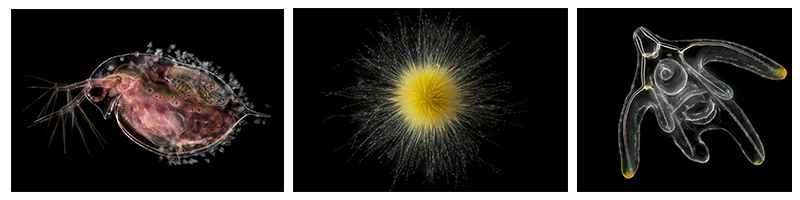

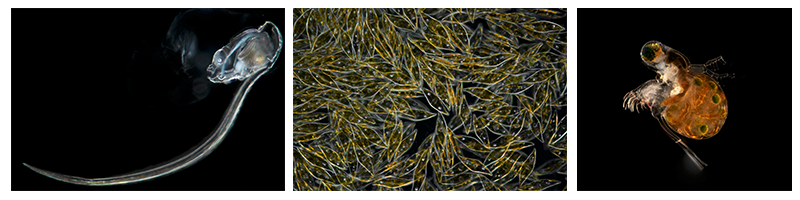

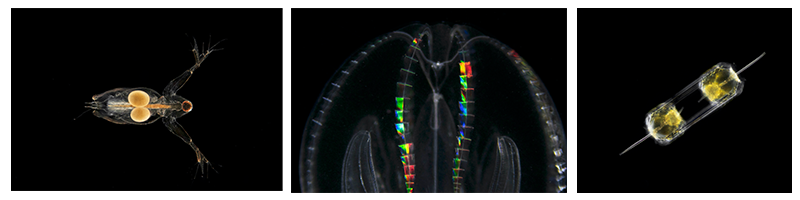

I think a couple of years ago I saw some pictures of plankton, and immediately I was struck. The colors, the incredible shapes, the beauty of it, the very fine detail. And also the fact that you can really look into the organisms. They’re transparent. You can see the inner workings. I think that’s really wonderful, and that on such a small scale. And people are not aware of it. It’s really everywhere, but you just don’t see it. And it’s only becoming visible under the microscope. The idea of revealing something like an invisible universe or an invisible world was really appealing to me. Later on, I heard of the importance of the plankton, the phytoplankton that’s taking care of almost half of the oxygen on Earth, the zooplankton that’s really the basis of the aquatic food web. It’s even more interesting if you become aware of the importance of the tiny creatures.

And how long have you been working on the plankton project?

Three years.

Tell me the process. How do you do it?

The first step is quite simple. You go outside with your plankton net, a very small mesh net. You throw it in the water, and then you pull it. The water goes out and the organisms go in the glass. You take it home. Then I go for the first examination with my stereo microscope. Then, what’s in it? Often I’m surprised, because every time I find new things, like new organisms. It’s always like a discovery.

Then I filter, examine the species, and then I think, “Oh, that’s interesting. That’s interesting.” I take my pipette and put them on an object glass, and then under the light microscope, and start filming with my trinocular microscope. I start either time-lapsing or filming, because the film consists of both time-lapses and video mixed together. I want to film everything as living organisms. That was very important. Normally you see only the diatom, but by time-lapsing it, I am able to capture the movements of the internal organelles. Sometimes maybe I take 400 photos, and then put them together, and they form a small clip. Sometimes the organism is moving slowly, then I film it.

Do people sometimes see you in the water and wonder what you’re doing?

Yes. When I’m working near the sea, for example, and I throw my net, people looking at me ask, “What are you doing?” Because they see I’m not fishing. But what then? And I say, “I’m catching plankton.” “What’s plankton?” “These are the guys that make the sea light blue in the summer, and then they make the sea sparks.” And that’s true. In the summer in Holland near Katwijk, near my house, sometimes on a very warm evening, you see that. But it’s only one of the very, very many species.

And are you able to identify every one of them?

Not yet. Most of it I identified, but there are still some organisms that I didn’t. I still don’t know what it is.

How many different kinds of plankton are there?

I have no idea. Must be thousands and thousands. Maybe millions. I don’t know. It’s incredible. And I only work in the Netherlands. In the open ocean, there must be whole other species, and a lot more. Some are millions of years old, like cyanobacteria. They invented oxygen, and they’re still here. And sometimes in almost unchanged forms. I find it so interesting that you can still find that kind of species in the water. I think they will survive. And the question is if we will survive, but they will, I think.

What’s the most surprising thing that you’ve found?

It’s a difficult question, because there were so many surprises. One of the surprising things was that the water fleas, which are pretty common species, have live young in them. You see them. They’re transparent. They develop. It’s in the film. For me, they are little miracles. Because if you realize the scale, it’s really invisible. Such a tiny organism, or animal, is able to develop young and give live birth. For me, it’s still incredible.

Is there an image that strikes you more than any of the others?

Well, maybe the image of the diatom, the yellow diatom, which has the structure of a beautiful honeycomb.

How did you decide to organize your footage?

I decided to make it a kind of abstract film, to do the montage on forms and colors and rhythm. That was my starting point. A friend of mine here from Leiden helped me to finalize the edit. I knew from the beginning that I didn’t want music. I never use music in my films, because I think it very much puts you in a certain direction. If you listen to this film with classical music, you go with a totally different mindset than when you go to the film with pop music, and I didn’t want that. I wanted a natural sound from the beginning. I knew I wanted underwater sound with it.

Do you feel lucky to have found Norwegian artist Jana Winderen for that job?

Yes. She has been recording underwater sounds with her hydrophones for maybe 20 years or so. She has the same dedication I have. Because I was immediately totally crazy about her sound, I thought, “This is it. This is what I want.” She saw my pictures and said, “Hmm, this is what I like.” So there was a great match. Immediately she said, “Okay, I want to make a sound composition for you.” So she, from her huge archive, made, especially for my film, this composition of her underwater sounds, which are very strange abstract sounds, totally fitting to the film, I think. There are sounds from within icebergs, sounds of whales, dolphins, but also fish howling to the moon.

Where do you go from here?

I think I will be moving on. I have an idea for a very large project. Maybe return to the plankton another time. But it will be in the same vein. It’s all about life, biology, secrets of nature. The next project will be more like the place of the human in the whole environment, the similarity of a lot of processes.

All photos by Jan van IJken.