It’s 1969, in the middle of the Gulf of California. Above is a blazing hot sky; below, the blue sea stretches for miles in all directions, interrupted only by the presence of an oceanographic research ship. Aboard it a man walks to the railing, studies the water, pauses to consider, then slips over the side. This is Bill Hamner.

On this day, Hamner will unknowingly set into motion a series of events that, several decades later, will result in multiple National Geographic articles, the birth of an international tourist destination, and a fundamental shift in how scientists think about open ocean biology. But Hamner doesn’t know any of this. At this moment, he is both literally and figuratively treading water. He’s hot, the deck is sweltering, and he’s looking, desperately, for something meaningful to do with his career.

The biologists go about their work as if this is how it should be.

Hamner doesn’t really belong onboard. An ornithologist by training, he has dedicated his career to understanding the inner workings of birds; already he has illuminated some of the physiological mechanisms that calibrate the breeding cycles of avian bodies to the sun’s rise and set. He does this ornithology work as an assistant professor at the University of California, Davis, a valuable position because it offers the possibility of tenure, and tenure means security for his wife and two small children. But then Hamner broke out in hives. He started having asthma attacks. After years of close contact, he had developed a devastating allergy to birds.

Hamner released his house finches and starlings and bobolinks. But what would he do next? He tried growing jellyfish and wound up with stinging vats of jelly goo. He tried growing moths instead and ended up with a freezer’s worth of rotten apples. Now he was here, his presence on the expedition a favor from the oceanographer who was running it, hoping for a clue as to what he might do next.

During his time on board, Hamner has watched his fellow biologists walk around the deck, deploying giant nets with big metal cranes. The nets sink into the cool deep, where they’re dragged for hours before being hauled back to the surface. Everything inside them is a sloshing, shredded slurry. Not a single animal appears unharmed. The biologists go about their work as if this is how it should be: piecing together the lives of ocean animals by picking through buckets containing their literal pieces.

In fact, this is the way most marine biology in the open ocean, the vastness beyond coastal waters, had been conducted. While renegades like William Beebe—the first man to traverse the deep in a submersible—insisted on being in the water, most biologists traveled the ocean at the remove of a vessel’s deck, hauling marine life up for examination. Hamner couldn’t work this way.

Today, Hamner and his wife Peggy, who worked alongside him throughout his career, are retired and in their 80s. Though they now live far from the ocean in Northport, Alabama, their home is filled with sculptures, photographs, and drawings from decades working on the water. Reflecting on his motivations, Hamner told me, “To study the natural history of any animal in its own environment, one must observe it undisturbed over time.”

He’d been trained as an ornithologist; he had watched birds in the wild and studied them in aviaries. He had to see the whole living animal. And on that sweltering day in the Gulf of Mexico, he absolutely had to get off the frying pan of a ship’s deck.

His face mask secure, Hamner plunged into the ocean and looked around.

Organisms resembling translucent bowls, which Hamner recognized as jellyfish, pulsed through the current. Comb jellies shaped like stemless wine glasses shimmered with rainbow patterns. Hamner’s eyes settled on rhythmically-beating, barrel-shaped creatures, roughly the size of his hand, which clenched and relaxed like the valve of a heart. Hamner vaguely recognized them, as he had a jar of something similar back at his lab. It was labeled “salp”: a group of invertebrates closely related to vertebrates. But this salp was smooth and robust, not at all like the mangled pile of jelly in his jar.

Bruce Robison, a friend on the expedition, joined him in the water. Robison was a marine biologist through and through—but unlike Hamner with his birds, Robison had spent his career far removed from the life he studied, using nets as other marine biologists did. It wasn’t until Hamner came aboard that someone thought to jump into the open ocean and immerse themselves in the world of their study subjects.

“There’s this phrase about a feeling for the organism,” says Michael Dawson, a marine biologist at the University of California, Merced. “And that’s what Bill brought.”

Hamner and Robison spotted a fish hovering in the water, watching them swim. Looking closer, they realized that the fish was inside a salp, hiding in the open central chamber while the clear barrel beat around it. As if the fish were also an explorer, riding in a salp submarine.

“Robison went back to the ship,” recalls Hamner now, and vowed to throw out his nets. Later he was hired by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, where he became a pioneer of studying midwater ecology with remotely operated vehicles. As for Hamner, he was enthralled. If all that life could be seen just below the surface, what else might be out there? He had found something new to do with his life.

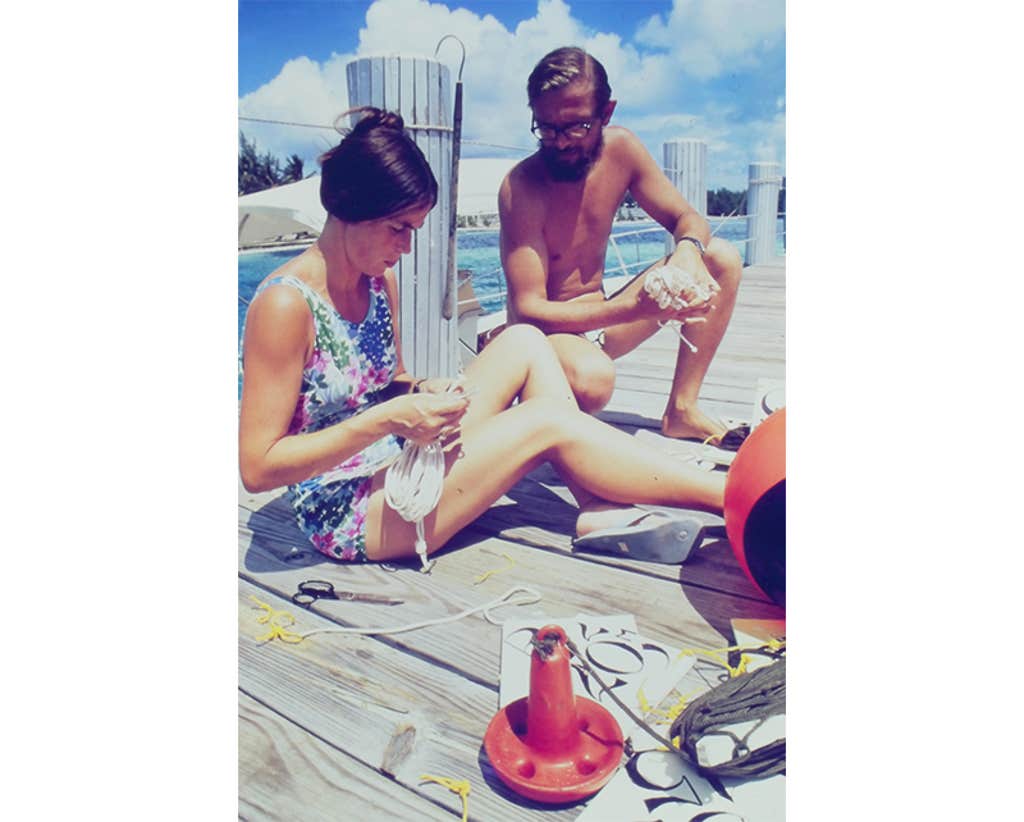

When Hamner returned home he told his wife Peggy, who’d always wanted to be an explorer herself. Peggy had trained as a scientific librarian, but she dropped out after they were married, following her husband, as most women did in those times. But, like her childhood hero Osa Johnson, she dreamed of trekking through jungles and sailing over uncharted waters. Together, Bill and Peggy Hamner hatched a plan: They would visit as many marine labs as they could, settle on the best for diving in the open ocean, and develop a method to study life between the ocean surface and the deeps, a region that sailors called the “blue water.”

They eventually settled on the small Bahamian Island of Bimini, off the coast of Miami, Florida. They recruited a handful of students and pooled all the money they could find, from student scholarships to National Science Foundation grants. Then, with their two young kids in tow, they set off for Bimini.

Things did not start well.

A shark ate my weight belt.

When they arrived they discovered that there was no room for them in the Lerner Marine Laboratory’s visitor housing. In desperation they rented half of a nearby duplex. The Hamners and their kids slept in one room, their students in another, with one student sleeping under dining room chairs so no one would step on him in the night. Hamner’s father, who’d accompanied them to help with childcare, slept on the porch. Eventually they moved into a half-built house with the beams and bricks exposed. Short on funds, the students would wander to the local sportfishing dock, asking fishers to donate the meat of their catch.

During the day they loaded a small boat with their SCUBA gear and started experimenting with blue-water diving. This too started poorly. “A shark ate my weight belt,” recalls Alice Alldredge, one of Hamner’s former students. She had dropped the belt and was swimming to fetch it when a shark swam underneath and swallowed it whole. Another shark slammed Peggy Hamner in the back. Sharks, it seemed, were a problem. The team started carrying long wooden sticks on their dives and used them to poke the sharks away.

Slowly, they built up a method for blue-water diving. They worked out a technique involving a weighted rope anchored to a float and a contraption they called the “trapeze.” All the divers clipped their own ropes to the central trapeze, and a safety diver floated at the nexus, watching everyone, ensuring that no one got tangled or detached, or sank too deep or drifted away or got attacked by a shark. And because the animals of the open ocean are almost completely transparent, the divers determined that the best way to spot floating life was to look slightly up, toward the sun, searching for the shadows creatures made as they passed in front of the light.

“Dropping slowly into the clear blue water as the light darkened, and visibility expanded forever, made me feel like an astronaut floating in space,” recalls Peggy Hamner. “Every dive.”

One day after diving, Bill Hamner brought back a jar with a large clear butterfly-like animal inside. He gave it to one of his students, Ron Gilmer, who was studying snails. “Oh my gosh,” Gilmer said, grabbing the jar. “I think this is Gleba!” Gleba were, and still are, among the open ocean’s most elusive snails. They flap two extensions of their body, like wings, and have clear crystalline shells that look a bit like glass slippers. Very few people have seen one, and almost no one has seen one alive. Over the coming days Gilmer documented wild Gleba for the first time, and in so doing, discovered something totally unexpected.

“They feed with mucus,” he told me. “Giant balls of mucus.” As they drift, Gleba hang from the base of a large balloon made from snail slime. They sail on these until the mucus collects a mass of floating edible particles, at which time the snails slurp the whole thing up, mucus and all. No one had ever seen a snail feed this way. For days, every time Gilmer went out he watched as whole fields of Gleba drifted by, the water crowded with clear balloons and the butterfly-like snails who flapped beneath them. But then one day they were all gone, as if they’d never been there.

The Hamners and their students would go on to describe how open ocean species drift with currents that quickly shift and change, washing animals in one day, drawing them out the next. Gilmer would publish his paper on Gleba in the prestigious journal Science, with Hamner insisting that Gilmer, who did much of the work, be the sole author—a generosity that’s virtually unheard of today, where academic culture demands that most senior scientists add their names to papers even when not particularly involved. Hamner’s student Larry Madin would discover that salps, those heart-pumping glass barrels, are some of the ocean’s most efficient feeders. After his time at Bimini, Madin would go on to study salps at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, where he found that salps may export large amounts of carbon to the deep ocean.

While in Bimini, Alldredge and Bill Hamner noticed a flurry of snow-like particles that always seemed to drift around them in the blue water. Hamner and Alldredge collected samples, with Hamner even constructing a small oven to dry and weigh them. Alldredge would later go on to conduct pioneering research on this phenomenon, called marine snow. She would eventually be inducted into the National Academies of Science. Another student, Neil Swanburg, studied large comb jellies that floated like Christmas tree ornaments in the water. He went on to study these and other open-ocean organisms, making important discoveries about their biology and role as open-ocean predators.

Dropping slowly into the clear blue water as the light darkened made me feel like an astronaut floating in space.

Bill Hamner was back on track. He now had a new field of study, successful papers and grants, and his students were becoming experts in their own right. Hamner was offered tenure at UC Davis on the basis of his work in Bimini and his earlier work with birds. But the time Hamner and Peggy spent at Bimini changed things. They were explorers now, and job security was not as appealing as it had once been. Together they decided that Bill should turn down the offer; they traded a stable academic life for the life of drifters, just like the species they studied. They wouldn’t always know when and where their funds would come from, but in exchange for that uncertainty they could explore and travel on the currents of an endless curiosity.

In Australia, they documented the critical importance of floating open-ocean life for coral reefs, and described how open-ocean animals would drift toward shore and be consumed by hungry corals and reef fish. In Palau, they conducted the first studies on jellyfish in saltwater lagoons, literally cutting the first trail to the now-celebrated Jellyfish Lake. They brought along a team from National Geographic who would make that lake’s golden jellies famous, drawing visitors from around the world and spawning a whole industry in the region. In Antarctica, they were the first scientists to document the schooling behavior of Antarctic krill, diving into massive schools that shifted like starling murmurations around them.

Together they gave rise to academic fields that produce new generations of scientists every year, and fundamentally changed the way we see the open ocean. “He took sampling off ships and coasts and into the blue water of the pelagic ocean,” Dawson recently told a packed audience at the 7th International Jellyfish Blooms Symposium, where he gave a speech honoring the Hamners’ work.

The Hamners dove where no one had, cut trails to places hardly seen, and swam with some of the most important species on Earth, all while raising two children and living year-to-year off what grants they could acquire. In 1988 Hamner was hired as a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. No longer diving, they’ve now come to rest at the University of Alabama, where they teach in an outreach adult education program: two tenacious, curious, infinitely adventurous scientific visionaries. ![]()

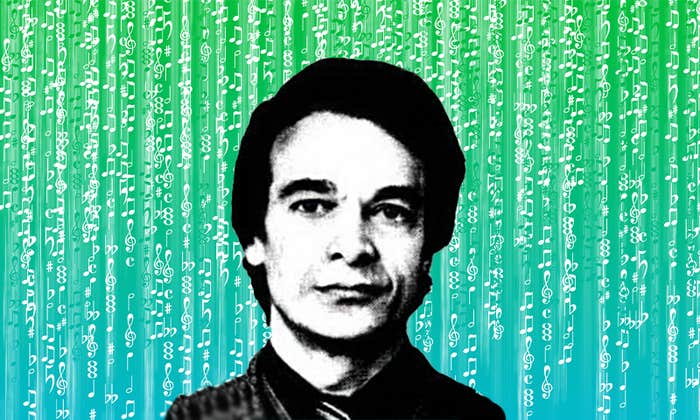

Lead photo by Laurence Madin