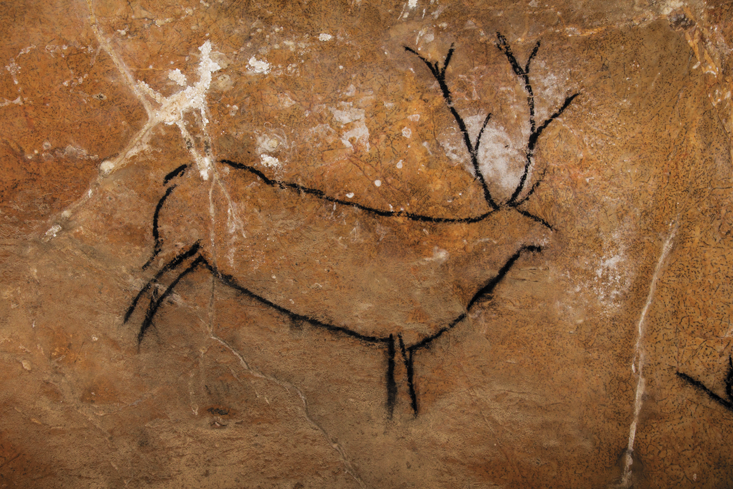

When I started learning about the Ice Age, the oldest known cave art dated to about 35,000 years ago—now it’s closer to 41,000 years. And while they seemed like a fairly intelligent species, Neanderthals weren’t thought to have been capable of creating art (the first confirmed Neanderthal cave art—an engraved crosshatch—was announced in 2014). Most researchers didn’t think our ancestors interbred with Neanderthals (but a number of them actually did around 60,000 years ago), and we definitely didn’t know that there was a third separate humanlike species called the Denisovans living in Ice Age Europe—and that some of us carry their genes, too. The remarkable fact is that all of us living today are the end product of an incredible story of success against all odds: Each of us carries DNA that stretches back in an unbroken line to the beginnings of humanity and beyond.

Paleoanthropologists have to be fairly flexible and open-minded about our theories, as we just never know when a new discovery or innovative research project could reveal previously unknown possibilities. I encountered this ground-shifting experience firsthand while working on the initial stage of my database of Ice Age symbols. At that point my goal was to gather all available information about the signs from existing sources (archaeological reports, academic articles, cave art books, etc.) and build it into inventories that I could then use to compare signs between rock art sites.

The prevailing opinion in Paleolithic art at that time was that Europe was the birthplace of art, invented by the first modern humans soon after their arrival on the continent. Based on this time line, the cave signs were thought to have started out around 35,000 years ago as simple, crude markings. Only much later—say, around 20,000 years ago—did the number, variety, and sophistication of the abstract motifs supposedly increase as the artists mastered this new ability. This was the assumption I was working with when I first started to compile those inventories back in 2007/8. I thought I would find only a small number of rudimentary signs at early sites, followed by the predicted increase over time.

I was wrong.

At first I had only a hunch that I was wrong—along with much of the literature. The thing with building a database is that you can only do it one site at a time, and it’s not until the end, when all the data have been assembled, that you can finally run tests to see larger patterns emerge. However, even as I sifted through hundreds of pages about the art, I sensed I was seeing a fairly wide variety of signs, even at the earliest sites. I resisted the urge to run the data before they were all in and complete, though.

After several months of data entry, the day finally arrived when I could search the database for the oldest geometric signs. As the results of my query showed up on the screen, the hair on the back of my neck literally stood on end.

Two-thirds of the signs were in use at the earliest sites. Even as early as they were, they were already distributed across a large geographic range. My first thought when I saw this astonishing result was, “There’s no way this is the beginning of the signs.”

Did they experience self-awareness? Could they tell jokes? Did they believe in worlds beyond what they could see?

These results got me pretty excited, because for much of the 20th century the majority of paleoanthropologists thought the modern mind emerged somewhere around 40,000 to 50,000 years ago, in a rapid event known as the “creative explosion.” Some people believed this transformation occurred because of a genetic mutation, others that it was environmentally driven, or a sociocultural change, or some combination of the above. Africa was seen as the place of incubation for the human species, but Eurocentric paleoanthropologists assumed that all the interesting changes took place either during the migration out of Africa or after these ancient colonists had spread out across the Old World. Earlier waves of people had already left, but this is the time when the main waves of human migration moved into Europe, Asia, and beyond.

The arrival of modern humans in Europe around 40,000 years ago marks the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic (also often referred to as the Ice Age in Europe). At the start of this era, the invention of new types of tools accelerated and the creation of symbolic artifacts (jewelry, cave art, ivory figurines, etc.) increased exponentially.

There were some sites prior to 40,000 years ago in Africa where a hint of symbolism might have occurred on some well-designed tools or on a bone with a few scratch marks (though these were usually dismissed as being a by-product of butchering prey). Overall, though, most 20th-century scientists believed that the people who lived before the “creative explosion” were not fully modern like we are.

Now, however, these attitudes are changing. African examples of art from the Ice Age remain comparatively few, but more discoveries are being made, and more frequently than ever before. In the past two decades the traditional perception of where and when the creative explosion took place has been seriously challenged. There’s even some doubt now about whether it was an explosion at all.

Seeing how well established the geometric signs were at this early date, and given the conventional wisdom of that time, I felt as if a piece of the puzzle had just clicked into place. The ancient age of the signs also raised some very interesting questions. If producing abstract markings was already a widespread practice when the first humans arrived in Europe, where and when did it start? And, if people were already fairly fluent in their use of the signs, doesn’t that mean they were already able to think symbolically?

Although my main focus was on the European Upper Paleolithic, I realized that in order to really comprehend the symbolic capacity of those first arrivals in Europe, I needed to delve into the cognitive origins of our species and trace the roots of these abstract abilities back to their birthplace in Africa.

Instead of just accepting what they could find naturally in the landscape, these people had begun to shape the world around them to their needs.

Homo sapiens first emerged as a distinct species in Africa somewhere around 200,000 years ago. Of course, this doesn’t mean that one day our ancestors were one species, and by the next day—or year, or even generation—they suddenly became modern humans. Evolution is a slow process. But geneticists and anthropologists have, nevertheless, been able to pinpoint a time frame in which most of the distinct genetic traits that make us human appeared—that made us different enough from other existing species that we became a species of our own.

So by around 200,000 years ago, people were living in Africa who were just like us: anatomically modern humans. Physically they looked the same as we do, and their brains were identical in size to ours. What we don’t know is if they were already thinking like us—or when they started to. They don’t appear to have been burying their dead, or wearing jewelry, or making decorative marks on their tools, or anywhere else for that matter. We don’t find evidence for any of these practices for another 80,000 years.

In other words, they were us, but at the same time maybe not quite us. I often wonder what it must have been like to be one of the first modern humans to walk this earth. Frankly, even as a paleoanthropologist, I find it hard to wrap my head around what that question actually means: If they didn’t yet know how to use their imaginations, or make art, or use symbols, then what did they think about? Did they experience self-awareness? How did they interact with each other? Could they tell jokes? Did they believe in worlds beyond what they could see?

Since we are looking for evidence of mental changes that took place within the soft tissue of the brain, we can’t identify them directly, but luckily there are other ways to gauge how our ancestors’ minds may have been developing. To this end, researchers have compiled a list of practices and artifact types that strongly hint that symbolic thought processes are at work. Evidence includes the selection and preparation of specific shades of ochre, burials with grave goods, personal ornamentation, and the creation of geometric or iconographic representations. If most or all of these elements are present, the chances are good that you’re dealing with fully modern humans.

East of Cape Town, down along the curve of the southern coast, is a tranquil U-shaped cove called Mossel Bay, with a town that bears the same name nestled on a triangular headland forming one end of the bay. The land here is relatively flat and open, and it slopes gently down toward the Indian Ocean before coming to an abrupt end at the top of the cliffs that form the sides of the promontory. This area is known as Pinnacle Point. Honeycombed with dark cave openings, these cliffs contain some of the earliest habitations of modern humans found to date.

During the early days of our species, Earth was in the grip of a severe climatic downturn. Around 160,000 years ago, much of North America and Europe were under ice, and the climate in the North had a dramatic ripple effect on the environment in Africa. Most of the interior of the continent was arid and uninhabitable, driving the small populations of humans living at that time to seek refuge in coastal habitats.

Starting around 160,000 years ago, the people living here began collecting pieces of ochre. As with the earlier people at the Twin Rivers site in Zambia, they weren’t just picking up any piece of ochre; they were very selective in their color choice, and bright, saturated red hues were their favorite. If they couldn’t find the color they wanted, they altered the natural shade of the pigment by heat-treating it. Somewhere along the line they had discovered that if you heat up pieces of ochre to a certain temperature and for a particular length of time, the color changes: yellowish ochre becomes red; red ochre becomes redder and darker. They may not have had a word for chemistry yet, but that is exactly what they were doing. Instead of just accepting what they could find naturally in the landscape, these people had begun to shape the world around them to their needs.

More than 300 pieces of ochre, many of them showing signs of having been ground for powder, have been found to date at cave 13B and its neighbors. This ochre may have been used for some everyday activity, but based on the inhabitants’ preference for bright-red ochre and their deliberate heating of some pigments to alter their color (there wasn’t a lot of naturally occurring bright-red ochre in the neighborhood), it seems more likely that these powders had a symbolic purpose. In another striking development, starting around 100,000 years ago, the residents of Pinnacle Point began to use a broader range of red colors—every shade from deep crimson to dark brown. This increased complexity in color choices could mean that cultural activities, such as body decoration or ritual use, were influencing their preferences for specific shades. The ochre powder could have been used for individual body painting or some type of ritual performance. If true, these ancient people were certainly behaving in a very modern way.

On top of that, a piece of red ochre with three notches on one edge and another ochre pebble engraved with a single open-angle chevron on its side were found in layers dating to around 100,000 years ago. These are not the only geometric engravings from this era. Pinnacle Point is one of a growing number of early sites forcing us to rethink when and where early humans made the transition to being like us in mind as well as body.

The caves of Es-Skhul and Qafzeh are two sites near each other, the first on the southwest side of Mount Carmel, and the other 15 miles to the east, near the town of Nazareth in Lower Galilee. Their similarity in age and in the types of symbolic activities found there, however, lead most researchers to talk about them together. These are the sites of the oldest intentional burials currently known in the world. Located within what is now the Nahal Me’arot Nature Reserve, the dark entrance to Es-Skhul can be seen among the craggy cliff faces of Mount Carmel, many of which are composed of the remnants of ancient fossil reefs. It is one of several ancient sites discovered in close proximity to each other. Qafzeh is more isolated, its large rounded entrance situated halfway up the side of a valley just outside Nazareth in a strategic location with a sweeping view of the fertile Plain of Esdraelon below.

Burials with grave goods indicate symbolic behavior, important signals for the presence of fully modern minds with a lot of abstract thought processes in place. For humans, death is a symbolic event as well as a physical ending. When someone we know and care about dies, we don’t just dump his or her body somewhere away from our living space and forget about the person. We filter this experience through multiple areas of our brains, including memory, imagination, and mental time travel, which give death a whole other level of meaning. We remember people after they are gone, we imagine the existence of unseen worlds where they may now reside, and we can project our minds into the future to see the inevitability of our own deaths as well as those of the people around us. The inclusion of grave goods in a burial suggests a culture that was thinking about these things.

Throughout human history, each culture has developed its own specific set of funerary rituals. Many people believe that the life or essence or spirit of an individual extends in some form beyond death, and the way in which people are laid to rest often reflects how different groups envision this unseen world after life. The idea of an afterlife where loved ones go is very old, and a wide variety of ancient cultures developed elaborate ceremonies to mark this transition, including placing material goods, both valuable (e.g., gold) and practical (e.g., food offerings), in their burials. Several burials with elaborate grave goods date back almost 30,000 years to the Ice Age period in Europe.

But can we trace this practice back even further? Symbolic burials are likely to mirror the development of culture as well as broader cognitive changes. Not many earlier burials have been found so far, but the ones we do know about offer some tantalizing clues.

For decades the complex behaviors revealed by discoveries at Qafzeh and Skhul in the first part of the 20th century were treated as curious exceptions.

An archaeological layer at Skhul dating to between 100,000 and 130,000 years ago contains the remains of seven adults and three children. Even though some of the remains were found in a fairly disturbed state—spread out from their original resting place with bones missing—others were found intact in shallow, purposefully dug graves. One of the burials was found in a small oval grave, arranged in the fetal position with the lower jaw of a large wild boar placed between his chest and his arms. The intentional inclusion of the jawbone makes this the oldest known burial with grave goods anywhere in the world.

Four pieces of bright-red ochre collected from a nearby mineral source were also found in the cave. Three of the four pieces had been heated to at least 575 degrees Fahrenheit in order to convert them from yellow to red. The inhabitants of Skhul had prospected the landscape specifically for yellowish ochre with the right chemical properties to convert into red pigment. The selective gathering of materials and their probable heat-treatment almost certainly indicates a symbolic aspect to this practice, possibly similar to what we saw with the people at Pinnacle Point about 30,000 years earlier.

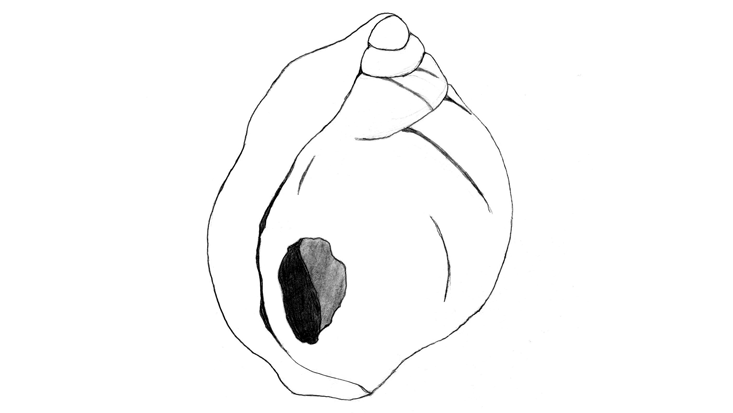

And that’s not all. Two marine shells were found in the same layer as the burials. Unfortunately, when this site was excavated early in the 20th century, clear records were not kept as to whether the shells came out of one of the burials or were just found in the vicinity, but we do know that they are from around the same period. During that time, the ocean ranged in distance from 2 to 12 miles from Skhul (depending on how much water was locked up in the European and North American ice sheets at the time), which makes it likely that the shells were brought to the cave intentionally. Both shells have perforations in locations that rarely occur in nature but are well-positioned for stringing. They were either picked specifically because of this feature or the holes were man-made, using the point of a tool. In either case, they were probably strung and worn.

The combination of the oldest burial with grave goods; the preference for bright-red ochre and the apparent ability to heat-treat pigments to achieve it; and what are likely some of the earliest pieces of personal adornment—all these details make the people from Skhul good candidates for being our cognitive equals. And they appear at least 60,000 years before the traditional timing of the “creative explosion.”

Qafzeh Cave also contains intriguing finds with symbolic potential. Buried there are the remains of at least 15 individuals, dating to between 90,000 and 100,000 years ago. Unusually, eight of the burials are of children. The graves are all clustered near the entrance and the south wall of the cave’s interior, and all come from the same archaeological layer, making it likely that these interments occurred within a fairly short period and that these specific areas of the cave had been designated for burying children. At Qafzeh, three burials contain grave goods and ochre. Below the feet of an adult skeleton is a large ochre block with an incised cupule (a circular hole made with the point of a stone tool) along with other scrape marks on its surface. Two shaped flint pieces and several fragments of ochre were found nearby. Since the area surrounding the burial does not contain anything similar, these are thought to have been intentional inclusions in the grave.

Around the skeleton of a 12- or 13-year-old adolescent, large blocks of limestone line the grave, possibly to keep out scavengers or to mark the burial. A deer antler still attached to part of the deer’s skull was positioned by the head and hands of the child, and another large limestone block was placed on top of the body itself before the grave was filled. A large quantity of ochre was also found within the burial but not in the surrounding area. The variety of materials found in this grave makes this burial the richest one known prior to the start of the Ice Age.

The third interesting grave may be the oldest known double burial. It contains an adult female and a 6-year-old, possibly a mother and her child. The two sets of remains are technically separate though in very close proximity (the child is located below the woman’s feet). Fragments of red ochre were found in both burials but not in the surrounding soil. The placement of two people in the same burial suggests that those doing the burying recognized the existence of a relationship between the two individuals and symbolically extended this connection into death and possibly beyond by keeping them together.

Besides the bits of red ochre that appear to have been purposefully deposited in certain burials, 84 other pieces of ochre have been found so far at Qafzeh. These are from the same time period, and 95 percent of the ochre is a strong shade of red. Many of these pieces were found in the western section of the cave along with ochre-stained artifacts, suggesting that this may have been an ochre-processing area. Given the presence of ochre in some of the graves, the ochre processing may have been specifically for their funerary practices. Yellow and brown ochre was also readily available in the landscape around the site, so a cultural color preference for red may have influenced the selection of ochre pieces.

Another set of artifacts from Qafzeh, which may have been used for symbolic purposes, are several clamshells, most coming from the layers below the burials. During the time early humans were frequenting Qafzeh, the ocean was almost 25 miles away, making it very unlikely that the shells ended up there accidentally. All the shells have a hole in the hinge area, but there is no definitive evidence of them having been made by humans, and this type of shell often has naturally occurring holes in this location. Microscopic analysis, however, shows that many of them were strung and probably worn. An analysis of the material found on the inside and outside of several of the shells suggests that they may have contained or come into contact with both red and yellow ochre. A stone core (a leftover piece of toolmaking rock) that may have been used as a rough mortar for mixing and preparing the ochre was also discovered.

The people of Qafzeh were engaged in quite a few symbolic activities: burials with grave goods; the collection and curation of ochre pigment; evidence for personal adornment. Another possible example of a geometric representation recovered from the burial layer is a piece of stone with two parallel, intentionally made incisions engraved on it. These markings, along with the circular cupule incised in the ochre block, were likely created for some symbolic purpose.

For decades the complex behaviors revealed by discoveries at Qafzeh and Skhul in the first part of the 20th century were treated as curious exceptions rather than as part of an early human trend toward symbolism and creativity. More recent discoveries, such as those at Pinnacle Point, suggest that researchers just may not have been looking in the right places.

The landscape of North Africa adjoins the region where Qafzeh and Skhul were found, so it seems like a logical place to look for other early sites. The problem is that presently the upper area of the African continent is the arid, inhospitable Sahara Desert, which acts like a natural boundary. It is so difficult to survive within its borders that it seemed an unlikely area for early humans to have settled. And with so much sand covering any potential sites, it was hard for researchers to even know where to look. But thanks to the modern research techniques of paleoenvironmental reconstruction (such as the study of lake sediments, the analysis of pollens from plants and trees, and the identification of bones from different animal species), we now know that, over the course of the past 200,000 years, the Sahara has gone through many different ecosystems. In fact, around 120,000 years ago, it was actually lush grassland with stands of trees, a multitude of rivers and lakes, and was populated by a wide variety of animal species. At other times, it looked like it does today, or something in between. Over quite a few periods, the Sahara was a perfectly pleasant place to live or to travel across.

Within the last 15 years, several sites have been identified in North Africa that contain artifacts similar to those found at Skhul and Qafzeh. The first is Sai Island, in Sudan, located in the Nubian region of the Nile River. This is the very earliest site with evidence of ochre use by modern humans. Occupied off and on by people throughout the Paleolithic, this island has many archaeological layers. The period we are most interested in dates from about 180,000 to 200,000 years ago, and excavation of this layer yielded large quantities of both red and yellow ochre. While red is almost always the dominant color at early human sites, the inhabitants of Sai Island seem to have preferred yellow pigment. To me this suggests that these people already had some sort of culture that was influencing their choice of ochre. Sai Island also yielded an even more intriguing artifact: a rectangular sandstone slab with a depression carefully hollowed out in its center. The slab appears to have been a grinding stone, with evidence of ochre powder within the depression. Two small pieces of chert stone with fragments of ochre still attached were found nearby. The pieces of chert were used to crush the ochre into a fine powder on the slab, like an early mortar and pestle. This could very well be the earliest example in the world of an ochre-processing kit.

Personal ornamentation and jewelry are a key type of symbolic behavior. Whether for purely aesthetic reasons or imbued with more complex ideas of identity and ownership, the emergence of collecting and displaying curated items points to a new way of thinking and interacting with the world. So far we have only looked at the two perforated marine shells from Skhul and the four clamshells with holes from Qafzeh. However, there are at least five occupation sites in North Africa, dating between 70,000 and 90,000 years ago, that also contain evidence of shell beads: Four are located in Morocco and one in Algeria. Almost all the shells come from the same species of marine snail (Nassarius gibbosulus) or very closely related ones with a similar shell shape—the same type of shell species that was also found at Skhul. Most of these sites are a significant distance from the prehistoric seashore (25 miles or more, with the site in Algeria almost 125 miles from the ocean), leaving no doubt that the shells’ presence at the caves was intentional. The shells of these tiny marine snails are anywhere from a quarter to a half inch across—about the size of a corn kernel—and the snails themselves were much too small, even in bulk quantity, to make a good meal.

The shells were most likely being collected to be worn. All 28 found at these North African sites have holes located in the appropriate part of the shell for being threaded. Microscopic analysis has proved that at least some of them were perforated using the point of a tool (scrape marks where the tool slipped can be seen in several cases). Holes in this location rarely occur in nature, so even the ones where the hole occurred naturally were probably selected precisely because of this feature. The interior edges of many of these holes also show signs of being polished, which is what you would expect a string or cord to do as it rubbed against the shell. The exterior of many of the shells also have a polished appearance consistent with the type of finish you would get if they had been worn against skin or clothing over time.

At least some of the shells from each site also bear traces of red pigment, and one shell in particular from the Moroccan site of Grotte des Pigeons was found completely covered in ochre. Neither ochre powder nor ochre pieces were found in the vicinity of the shells, so it is unlikely that they picked up the pigment by chance. Finding these two hallmarks of cognitive modernity together—personal adornment and ochre use—strengthens the argument for a symbolic motivation. These shells could have conveyed some type of agreed-upon meaning between group members and may well signal a burgeoning cultural tradition.

The deliberate burials at Qafzeh and Skhul along with mounting evidence for a widespread tradition of wearing shell beads as ornamentation in North Africa and the Near East are pretty clear evidence of symbolism. The number of new sites with symbolic artifacts found over the past two decades has really rewritten the time line for the emergence of the modern mind. Now it’s not so much a question of if the date of the “creative explosion” should be pushed back as a question of how far it should be pushed back. It is starting to look more as if this suite of symbolic practices from the “fully modern checklist” developed slowly, in Africa and the Near East, over a long period of time, rather than in a sudden burst.

Here in the present, we’ve been building on the mental achievements of those who came before us for so long that we rather assume that certain capacities, or ways of thinking, have always existed. That’s one of the things I find most compelling about researching our deep history. If you study the time period when many of the cognitive skills we take for granted—communication, art, and abstract thinking—came into being, you realize that these people didn’t have the shoulders of any giants to stand on: They were the original shoulders.

Genevieve Von Petzinger studies cave art from the European Ice Age and has built a unique database that holds more than 5,000 signs from almost 400 sites across Europe. Her work has appeared in popular science magazines such as New Scientist and Science Illustrated. A National Geographic Emerging Explorer of 2016, she was a 2011 TED Global Fellow, a 2013-15 TED Senior Fellow and her 2015 TED talk has more than 2 million views.

From The First Signs: Unlocking the Mysteries of the World’s Oldest Symbols by Genevieve Von Petzinger. Copyright © 2016 by Genevieve Von Petzinger. Reprinted by permission of Atria Books, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.