Tsipi Shaish, a 59-year-old grandmother, knows exactly when she became an artist: when she was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 2006. Before her trembling hands brought her to a neurologist, she had lived “a routine life,” she says. She worked a boring job at an insurance company for 25 years and focused on raising her two kids. She never took art lessons, and beyond the occasional museum visit, never gave any thought to art. Now she talks proudly of her own paintings that have hung in Paris and New York City galleries.

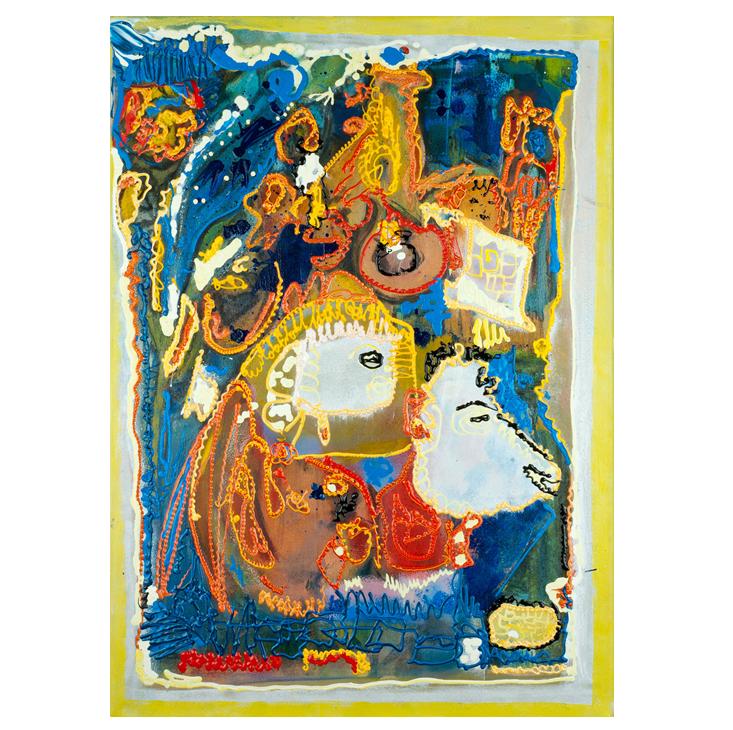

“I go to the canvas because I feel curious, I feel an uncontrollable urge,” she says. She chooses materials and paint colors in a haze of intuition, letting her hands apply strong swathes of color to create vivid abstracts. The Agora Gallery in Manhattan’s arty Chelsea District, which featured Shaish in a 2011 exhibition, states that her paintings function like landscapes with startling symbolism, combining bold colors and pastels in a “gleeful pandemonium.”

“If you ask me, ‘Why did you do this and not that?’ I wouldn’t be able to answer, because I don’t know it rationally,” Shaish says. Her creative impulses are an integral part of a new version of herself that only came into being after her diagnosis. “I’m more alive than I was 10 years ago,” she says.

Shaish is part of a subset of people with Parkinson’s disease who experience an urgent flowering of creativity even as their brain cells die and their bodies decline due to the neurodegenerative disease. Patients with no prior history of artistic proclivities begin to draw, paint, sculpt, and write poetry. In recent years case studies have shown the brains of the Parkinson’s patients are being reshaped by their disease and medications. Like most Parkinson’s patients, Shaish takes drugs that rebalance the brain’s dopamine system, involved in movement and motivation. There is a light side and a dark side to these neural changes. While some patients produce inspirational art, others get locked in destructive addictions. But drugs aren’t the only explanation.

Parkinson’s experts are finding that newly artistic patients like Shaish are tapping a well of creativity that had previously been sealed off. Their bursts of inspiration, the scientists say, offer insights into the neural mechanisms of creativity that lie within us all, and underscore the dictum that creativity flows when our filters are down and the world rushes in.

The underlying cause of Parkinson’s disease is not yet known. Its symptoms are the result of a signaling problem: Brain cells begin to die that produce a certain neurotransmitter, a chemical that triggers the action of other neurons. This particular neurotransmitter, dopamine, is critical in regulating movement, which explains why Parkinson’s patients often have shaking hands, stiff limbs, and overall difficulty in initiating and executing motor tasks. But dopamine doesn’t only work in the motor-control system. It plays a role in reward-seeking behavior, risk-seeking tendencies, and addiction.

James Beck, vice-president of scientific affairs at the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation, explains that patients’ brains change as dopamine levels drop and their production cells die off. Researchers think the neurons designed to respond to the neurotransmitter become more sensitive to the chemical as they wait in alert readiness for the dopamine signal. “These neurons are straining to hear, if you will,” Beck says.

A new version of herself came into being after her diagnosis. “I’m more alive than I was 10 years ago,” she says.

The symptoms of Parkinson’s are treated with two types of medication given at different stages of the disease. One mimics dopamine while the other provides neurons with precursor material with which to make the actual neurotransmitter, but both activate the dopamine pathways in the brain. Now imagine the effect on neurons with hypersensitive dopamine receptors when those drugs hit the brain. Cells that have been straining to catch a whisper of dopamine are suddenly being shouted at by a drill sergeant.

These brain changes and medications are common to all Parkinson’s patients, yet not all experience an outburst of creativity. Scientists can’t yet explain why certain people’s underlying brain chemistry makes them respond to dopaminergic drugs like Picassos. “Maybe sometimes people have a latent level of creativity that’s exposed, because not everyone who has Parkinson’s disease develops this creative drive,” Beck says.

Cindy DeLuz of northern California had worked as an esthetician before her diagnosis and had no history of making art; when she felt the sudden urge to paint, she had to drive to a five-and-dime store to buy a watercolor set. Within weeks she was painting obsessively, sometimes for 48 hours at a stretch. “My husband finally put a lock on the art room door,” she remembers with a laugh.

Such levels of compulsion ring alarm bells for clinicians who take care of Parkinson’s patients. In the early 2000s, doctors realized that a small number of their patients responded to the dopamine-related medications by compulsively seeking rewards, often in ways that screwed up their lives. Some patients lost their savings through compulsive gambling, others became hypersexual and destroyed their marriages, and some just wanted more and more of their medication. By 2005 researchers had classified these behaviors as dopamine dysregulation syndrome.

Anjan Chatterjee, chair of neurology at Pennsylvania Hospital, has seen cases of Parkinson’s patients who have engaged in these disruptive behaviors, and has also studied a patient who painted obsessively.1 He believes the two phenomena are linked. “There may be something in this constellation of symptoms where people have a certain amount of impulsiveness and risk taking behavior that gets expressed through art,” Chatterjee says. He says his artistic patient would get up at four in the morning to paint. “Our patient would pick themes and keep working them and working them,” he says. “There was a ritualistic component.”

Chatterjee notes that creativity is often conceived as a four-stage process. In the first preparatory step the artist acquires skills and gathers material; in the second “incubation” stage ideas swirl around the subconscious brain; third comes that wonderful moment of illumination where disconnected thoughts meld together in an exciting new way. Finally, in the fourth stage, the artist makes a conscious and deliberate effort and gets the work done.

Maybe, Chatterjee says, the dopaminergic drugs are influencing only the first and fourth stages of the creative process, which require focus and drive. He doesn’t see how the medications would help with the middle stages, which are characterized by lack of focus. “When we say that people with Parkinson’s have this burst of creativity, it might be more accurate to say they have a burst of production,” he says. “Whether they’re truly creative, whether they’re breaking new ground, is not so clear to me.”

That’s a possibility that occurred to Rivka Inzelberg, a neurology specialist and a researcher at the Sheba Medical Center in Tel Aviv. Some years ago, she began noticing a surprising number of her Parkinson’s patients bringing along art projects to show her during their office visits. In 2013 she surveyed the medical literature, collecting case studies of a few dozen creative Parkinson’s patients, learning about the confluence of medication and disease behind their output.2

While some patients produce inspirational art, others get locked in destructive addictions.

Last year, Inzelberg set out to test the hypothesis that patients’ art production was just a (fairly harmless, rather inspiring) manifestation of dopamine dysregulation syndrome.3 For the study, she had 27 Parkinson’s patients and 27 age- and education-matched control subjects take a battery of tests designed to measure their creativity. She also assessed the compulsive proclivities of all subjects using a standard questionnaire. The results seem to refute the hypothesis that creativity is a manifestation of drug-induced compulsion: The patients and controls scored similarly on her questionnaire, and the individuals with higher compulsive scores did not score higher on the creativity tests.

But the Parkinson’s patients overall performance on a few of those creativity tests was remarkable. For one task, subjects looked at abstract line drawings and listed all the images they saw. The Parkinson’s patients not only generated more responses than the control subjects, their responses were also judged more original by an independent panel. What’s more, those patients on the highest doses of dopaminergic medications scored highest.

Another test measured an aspect of creativity called divergent thinking—essentially the opposite of a logical thought process—by asking subjects whether two words were semantically linked. Unknown to the subjects, these word pairs fell into four categories: no connection, literal connection, conventional metaphor, and novel metaphor. Parkinson’s patients and control subjects had the same rate of success in assessing word pairs in the first three categories. But in identifying novel metaphors, of linking together two seemingly alien units of meaning, the Parkinson’s patients performed much better than the controls. So, for example, the patients could imagine a blanket of pity, or a scarf of fog.

Inzelberg thinks that dopaminergic drugs alone can’t explain the creative outbursts. She notes that other studies have shown brain damage from a stroke, or frontotemporal dementia—damage to lobes associated with planning, judgment, and speech—have inspired creativity. “Damage to the brain in certain areas might trigger the sudden appearance of skills that did not exist before,” she says. Interestingly, Inzelberg adds, “dopaminergic drugs will probably not generate creative skills in neurologically normal individuals.” Indeed, the neural degeneration caused by Parkinson’s helps stir the artistic flowering.

Shelley Carson, a psychology lecturer at Harvard University and author of the 2010 book, Your Creative Brain, adds another critical piece to the puzzle of Parkinson’s artists. Much of her research has focused on a mental function called latent inhibition, which is a person’s ability to filter out irrelevant stimuli and focus on the task at hand. Her studies have shown that people who aren’t very good at this kind of filtering are more open to new experiences, and also more creative.4,5

Latent inhibition is necessary because the world is a pretty over-stimulating place—if you tried to pay attention to all of it, you’d go crazy. In fact, that’s a problem that people with schizophrenia have, Carson explains. To reduce these patients’ hallucinations and delusions, doctors give them medications that have the effect of “reducing the amount of material that is making its way into conscious awareness,” she says. Those drugs work by bringing down levels of dopamine in the brain.

Medications that flood the brains of Parkinson’s patients with dopamine would have the opposite effect, Carson says. Because these drugs make the patients’ internal filters less effective, they have “more information to combine and recombine in novel and creative ways,” she says. So these creative Parkinson’s patients may gain access to the currents of sensations, half-formed thoughts, and ephemeral emotions that swirl constantly through the subconscious.

Inzelberg’s studies support the idea that high dopamine levels disrupt inhibition and boost creativity. “When there’s lack of inhibition, there’s more freedom for ideas to come up,” Inzelberg says. The Parkinson’s artists, she concurs, tap into a brain system for creativity that “we all share.” But because of neural degeneration, and the brain’s attempt to compensate for the damage, the “network is working otherwise, and is possibly even wired otherwise.”

People living with Parkinson’s would no doubt say that getting a neurodegenerative disease is not a great way to summon the muse. But they are not questioning the muse, only following her.

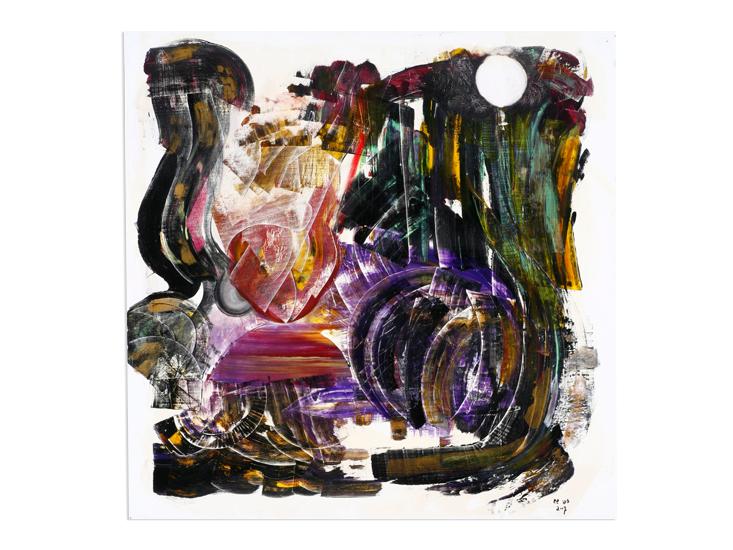

When she picks up her brush, Shaish says, she doesn’t know where she’s going. She recounts a winter’s night in 2007. One year after her Parkinson’s diagnosis, her husband was diagnosed with cancer, and had to stay in the hospital for rounds of chemotherapy. On her husband’s first night in the hospital, Shaish came home to a dark and empty house—her kids were grown and gone, so she was alone. She took up a big blank canvas and started reaching for the paints. She mixed dark colors: blacks, browns, purples, greens. She painted without a plan or an image in her head. “But when I finished and I sat down and looked at the painting, I knew exactly what it meant to me,” she says.

She gazed at a white circle atop a tiny white cross she had painted in the upper right of the canvas and saw “a Christian with curly hair, arms spread.” That figure stood above a swirl of black and purple that reminded her of a storm wave, poised to pull the person deep into the sea. Shaish thought of all the illness and suffering in her family, and vowed that she would not be a victim who accepted her lot, she would not meekly turn the other cheek. “That would drag me down to the bottom of the sea,” she says.

Then she shifted her view to the left side of the canvas, where a reddish shape like an overturned bowl spilled dark tendrils onto the floor. It reminded her of a Hebrew expression: “My life is like a bowl that was turned upside down.” Yet above that muddle, free flowing forms in white and pink rose up “like hope,” she says. Advancing off the left side of the canvas she saw a shape like the horse in a chess set. The painting was saying that her life might be “wild and crazy and problematic,” she says, but she would march forward nonetheless.

Shaish says the painting is like a Tarot card that her brain dealt her. “It’s as if my subconscious created this card for me and gave me strength and inspiration, told me how to cope, how to look at my life.” Shaish still struggles with her disease. She takes medications four times a day, and deals with tremors and muscles that sometimes go stiff and rigid. In the morning, she has trouble getting moving. Still, Shaish sees her condition as a gift. “It has made me attentive to my intuition,” she says. “I believe we all have the answers within us. If you really listen to yourself, if you pick up the right things, then you know the answers.”

Eliza Strickland is an associate editor for the science and technology magazine IEEE Spectrum.

References

1. Chatterjee A., Hamilton R.H., & Amorapanth P.X. Art produced by a patient with Parkinson’s disease. Behavioral Neurology 17, 105-108 (2006).

2. Inzelberg R. The awakening of artistic creativity and Parkinson’s disease. Behavioral Neuroscience 127, 256-261 (2013).

3. Faust-Socher A., Kenett Y.N., Cohen O.S., Hassin-Baer S., & Inzelberg R. Enhanced creative thinking under dopaminergic therapy in Parkinson disease. Annals of Neurology 75, 935-942 (2014).

4. Peterson J.B. & Carson S. Latent inhibition and openness to experience in a high-achieving student population. Personality and Individual Differences 28, 323-332 (2000).

5. Carson S.H., Peterson J.B., & Higgins D.M. Decreased latent inhibition is associated with increased creative achievement in high-functioning individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85, 499-506 (2003).