More than a decade before humans launched themselves into outer space, a tiny species made the journey first.

NASA first sent fruit flies on a mission in 1947 to see whether the intrepid insects would return to Earth in one piece, and enable us to consider sending humans there, too. If flies seem like an odd choice for such a dangerous test, know that they share about 60 percent of our genetic code.

Fruit flies, for example, age like us, get a little tipsy or hyper from beverages with alcohol or caffeine, and even serenade potential mates (hopefully this move is less cringy in insect romance).

Because our makeups have so many parallels, a new study released last week in Nature exploring how 140,000 neurons connect in the fruit fly brain could have wide-reaching implications.

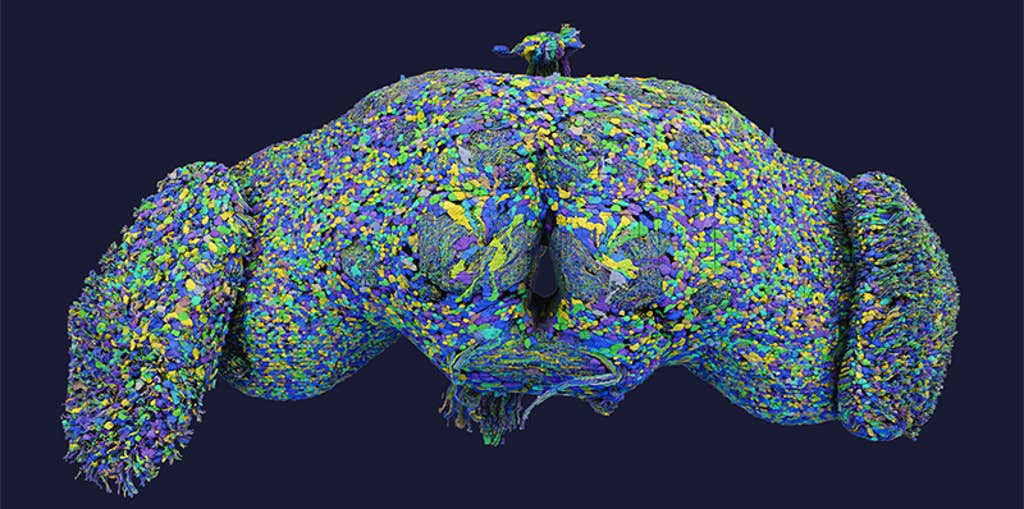

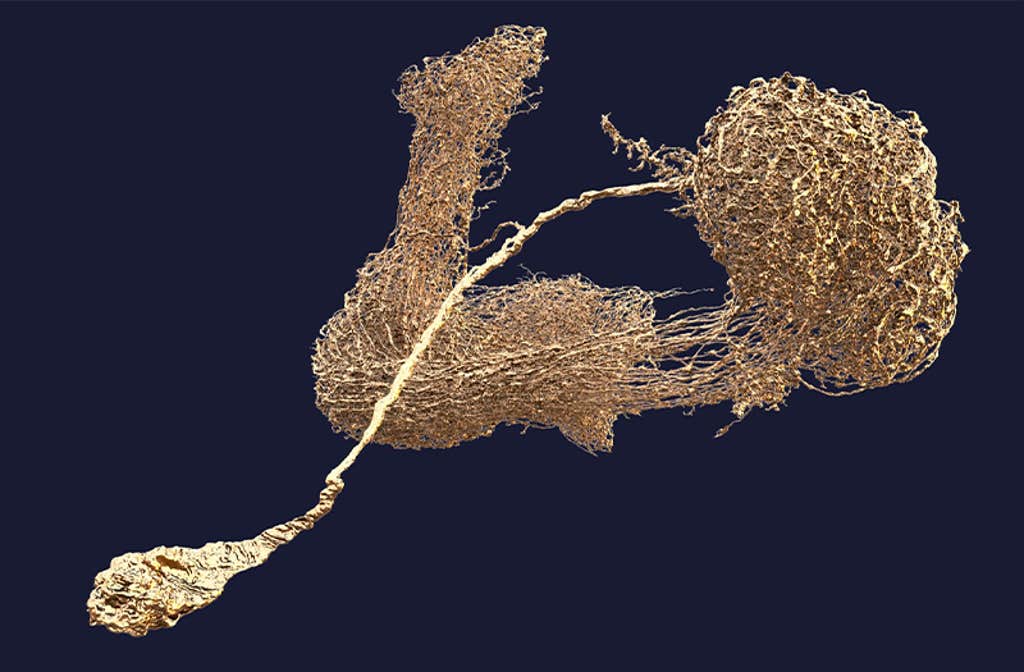

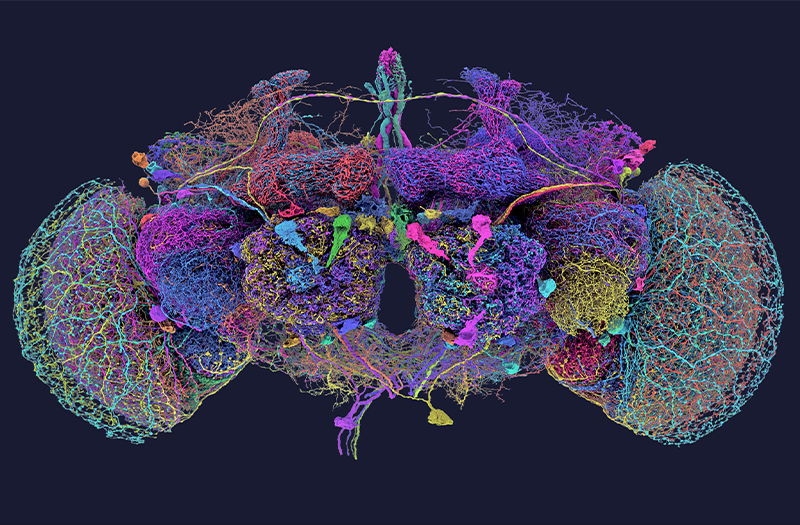

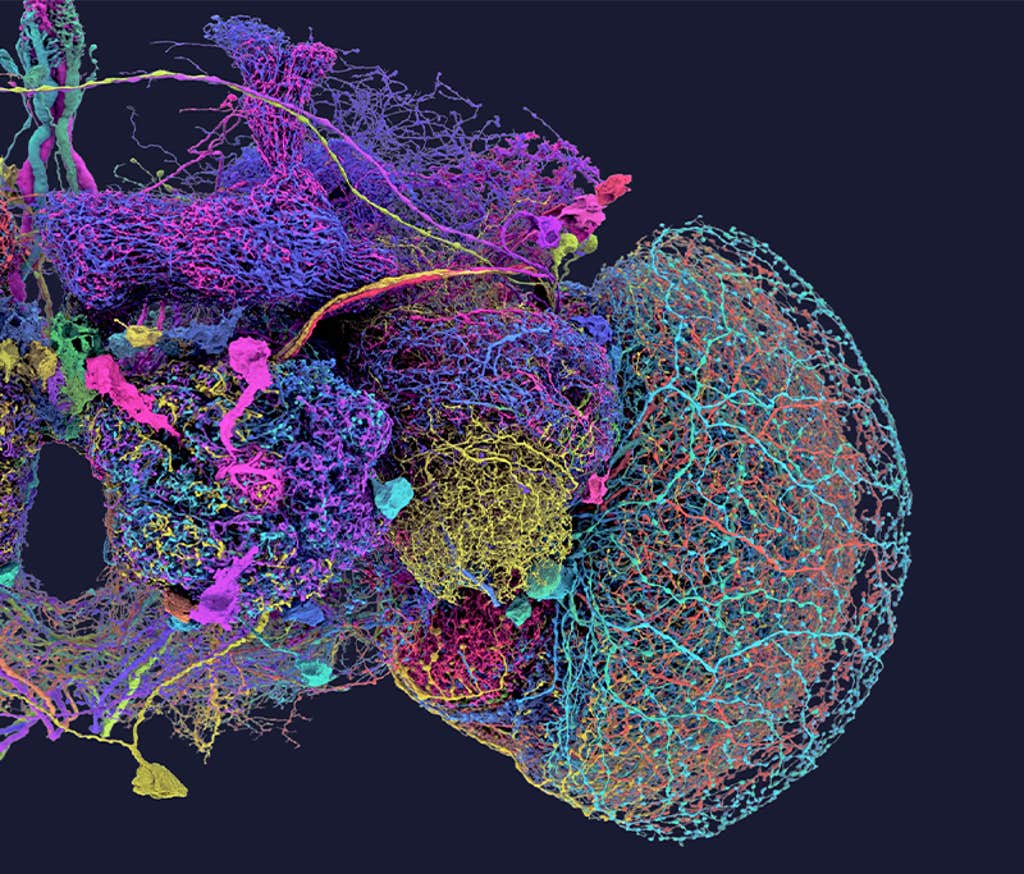

Hundreds of scientists have been working since 2013 to map the intricacies of the neural networks in an adult female Drosophila melanogaster, which connect through 490 feet of wiring. The research is accompanied by incredible reconstructions of the brain that illustrate how its myriad cells connect. The study is the most detailed map of an animal’s brain in existence.

Scientists published many of the diagrams and interactive 3-D models through FlyWire, the first-ever complete connectome of the adult fly brain in its entirety. They identified and annotated more than 8,000 cell types, 4,581 of which are new to researchers. In comparison, 3,300 cell types have been identified in humans, although what some of them do is still a mystery.

Included in the study are insights into how sensory signals communicate, prompting flies to walk, stop, or stick out their proboscises to eat. Although humans are 500 times larger than a fruit fly with a million times as many neurons, this research is an extraordinary leap forward in understanding how our brains function. ![]()

This story is adapted with permission from one that ran in Colossal magazine.

All images courtesy of Tyler Sloan for FlyWire, Princeton University, (Dorkenwald et al., 2024.)