Galileo Galilei is best known for his novel way of looking at Earth’s place in the solar system and his consequent problems with the Vatican. But long before all the fuss blew up over his cosmology, Galileo told us that while the physical attributes of the planet are present, they are perceptually nonexistent until they have been interpreted by our senses. This theory applies to wine as much as to anything else, and Galileo, who described wine as “sunlight, held together by water,” did not forget that fact. As he put it, “A wine’s good taste does not belong to the objective determinations of the wine and hence of an object, even of an object considered as appearance, but belongs to the special character of the sense in the subject who is enjoying this taste.”

Anyone who has ever attended a wine event knows the five S’s of wine tasting: See, Swirl, Sniff, Sip, Savor. The five S’s allow us to directly hit three of our five senses—sight, smell, and taste. This leaves us with two senses that we rarely associate with wine—hearing and touching. But ignoring them is a mistake. There are few things more satisfying than the classic Pop! of a Champagne bottle, however déclassé purists may consider it (they prefer an unostentatious hiss). More important, what a person has heard about a wine usually influences his or her perception of it. In fact, the multimillion-dollar wine advertising industry depends on this aspect of wine appreciation. As for that fifth sense, touch is also critically important in how we perceive wine—not through our fingers but through touch sensors in our mouths and throats. If we couldn’t feel the wine in our mouths, our experience of it would be incomplete.

The role that our senses play in our attraction to and appreciation of wine has been illuminated by generations of wine writers and critics. What has undeservedly received less attention is the brain, the hugely complex organ within which all that sensory information is processed and synthesized. We don’t just taste with our senses, we taste with our minds. And our minds are routinely affected by a host of influences of which, quite often, we are not even aware. Both our senses and our common sense can be led astray by any number of extraneous factors originating in what we know, or think we know, about the wine we are drinking. Figuring out how our minds work in such complex domains as the evaluation of wines—which are, among other things, economic goods—is the province of neuroeconomics.

Researchers discovered that individuals on average enjoy more expensive wines slightly less.

To study the relationship between consumer preference and, for example, the cost of wine, neuroeconomists typically set up blind experiments, in which the subjects are unaware of the parameters of the experiment. Researchers at the Stockholm School of Economics and Yale University have conducted a double-blind experiment—in which both the subject and the experimenters with whom they come into contact are unaware of the parameters involved—upon this relationship. Their sample of over 500 subjects included experts, casual wine drinkers, and novices. The experiment was simple. Subjects were asked to taste a succession of wines and rate them as Bad, Okay, Good, or Great. The wines ranged in price from $1.65 to $150, and the subjects were not told the cost. The responses for each wine were tabulated, and statistical analyses applied. Now, the average wine buyer might have hoped that this experiment would show that the price of a wine is correlated with its quality. This would certainly simplify life. But the researchers discovered that “the correlation between price and overall rating is small and negative, suggesting that individuals on average enjoy more expensive wines slightly less.”

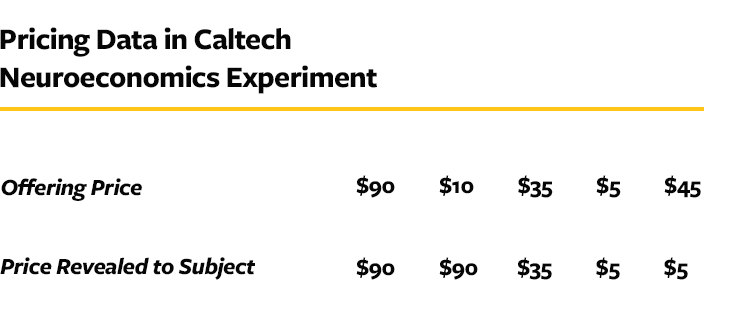

To explore this relationship further, researchers at the California Institute of Technology set up an experiment in which they examined not only the dynamics of preference but also which regions of the brain might be controlling such preferences, in light of cost. To localize these, they turned to functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). The tough part of using this method on taste judgments is that the subject has to lie completely still, so the researchers had to devise a pump-and-tube system to deliver the wine to their subjects. Then the researchers threw a complication into the study that allowed them to pinpoint whether knowledge of price affected perceptions of taste.

First, they bought Cabernet Sauvignon from three different vineyards: an expensive $90 bottle, an intermediate $35 bottle, and a rock-bottom $5 bottle. Their subjects were all young wine-drinkers (aged 21 to 30) who both liked and occasionally drank red wine, but were not alcoholics. They placed the subjects in their MRI machine, connected the delivery hoses, and told them they were going to taste five different kinds of Cabernet Sauvignon. For each of the offerings the subjects were told the notional cost of the wine (as listed in the table), and then the wines were pumped into the subjects’ mouths in a predetermined sequence, for a set amount of time. Subjects were then asked a series of questions designed to determine their preference for each of the “five” wines. The experiment confirmed that perceived wine cost was a heavy factor in choosing preferences. But the real revelation was that a region of the brain called the medial orbitofrontal cortex was hyperactive in every one of the subjects while he was making his choice. It seems that we all use the same part of the brain to make decisions about wine, at least when money is involved.

This experiment clearly showed that the subjects’ preferences for the wines used in the study were strongly influenced by what they believed the wines had cost, and that this calculation was processed in a specific part of the brain. That’s a start. But the subjects were relatively young and naive about wine tasting, and one might legitimately wonder whether an expert wine connoisseur would have been tricked in the same way. This experiment has not been performed yet, at least with an fMRI machine. But it seems likely from the literature that prior knowledge is a significant factor in most people’s appreciation of a wine.

The psychologist Antonia Mantonakis and her colleagues looked at preconceived notions from another perspective. Before giving the subjects wine to taste, the researchers first planted in their subjects’ minds either the notion that they had previously “loved the experience” of drinking wine or that they had “got sick” from it. Whether the subjects actually remembered their earlier drinking experiences in either way was irrelevant to the experiment, since virtually everyone has had experiences of both kinds at some time in their wine-drinking lives. What was important was the initial suggestion offered to the subjects. And the outcome was perhaps to be expected: People who were given the positive suggestion were more influenced by it, and consumed more wine than those who received the negative one. Clearly, the tasters’ responses were affected by extraneous factors, and the recommendation to retailers was that in selling wine they should try to call up the most pleasant possible associations in their customers’ minds.

Experiments like these lead wine advertisers to ever-subtler ways of influencing people to buy their products.

Neuroeconomists have also been able to demonstrate by experiment something that has long been understood from anecdotal experience—namely, that our perception of wine is influenced not only by what is in the bottle but also by what we see on the label. Researchers conducted blind experiments in which they evaluated the role of the shape and color of the label in forming consumers’ preferences for wines. Although both variables were significant in consumer choice, the colors of the labels were less important than their shapes, or the shapes printed on them. The most successful labels were brown, yellow, black, or green (or combinations thereof), with rectangular or hexagonal patterns. You might ask whether preconceived notions of cost might have affected the outcome of the experiment. But since they found no correlation of cost with label preference, the experimenters felt confident in their conclusions.

Does how much you know about wines in general influence how you perceive a specific wine? And what is the value of a name? To assess at least the first question (getting at the second would presumably have been too expensive), researchers gathered experts, moderately informed wine drinkers, and novices, and presented them with an advertising campaign for a particular wine, a Zinfandel, before the tasting. The variables in this case were the quality of the wine as assessed by external experts, and the subjects’ preferences. In all cases, the experts were unswayed by the mock advertising campaign, while it did influence the novices. Most interesting, though, was the reaction of the moderately informed wine drinkers, who chose the same wines as the experts if they were allowed to consider both the ad campaign and what they knew about wine. Given time to consider their choices, they were able to set their preference based on the quality of the wine. But if rushed, they turned in the same results as the novices.

The results of the initial experiment prompted the researchers to repeat it with only novice wine drinkers. But now, before the tasting began they educated their subjects for 25 minutes about wine and its quality. Those novices turned in the same results as the moderately informed group had done in the first experiment; and here, too, the key factor in judging the quality of the wines correctly was allowing the subjects to think about what they had been told in the training session.

On one level, experiments like these show that advertisers are learning more and more about what influences our choices in wine, leading to ever-subtler ways of influencing people to buy their products. Consumers thus need to be on guard, because it is clear that how one experiences a wine is affected by a host of factors, some of which might seem to be irrelevant. (Mantonakis and her colleague Bryan Galiffi even showed that consumers significantly tended to prefer the products of wineries with hard-to-pronounce names!) The good news, though, is that if you educate yourself about wine and you use this knowledge as a standard when tasting a new one, you will more often than not be able to judge its quality accurately.

By the time you’ve swallowed a sip of wine, it will have engaged all five of your senses. In fact, a great wine is capable of delivering one of the richest multidimensional sensory experiences you will ever have—also, regrettably, one of the most expensive. Indeed, however you may score or describe the color, the clarity, the nose, the taste, and the mouth-feel of a wine, the end product will inevitably be summed up by just one number: the price. Although price and expectation go hand in hand, price and quality do not necessarily do so. It’s a confusing market. So it’s hardly surprising that a profession has grown up around the sensory evaluation of wine as an aid not only to its production, but to its consumption.

Once upon a time, the top English-speaking wine critics were British. They were, by and large, aesthetes who celebrated wine as part of a much larger total experience of life. They tended to describe the wines they evaluated in relatively abstract and stylistic terms: A wine was aristocratic, lean, restrained, or voluptuous. Eventually they began ranking wines by awarding stars to them (usually between 1 and 5), and then, as the profession became a little more focused, by adopting a 1 to 20 scale.

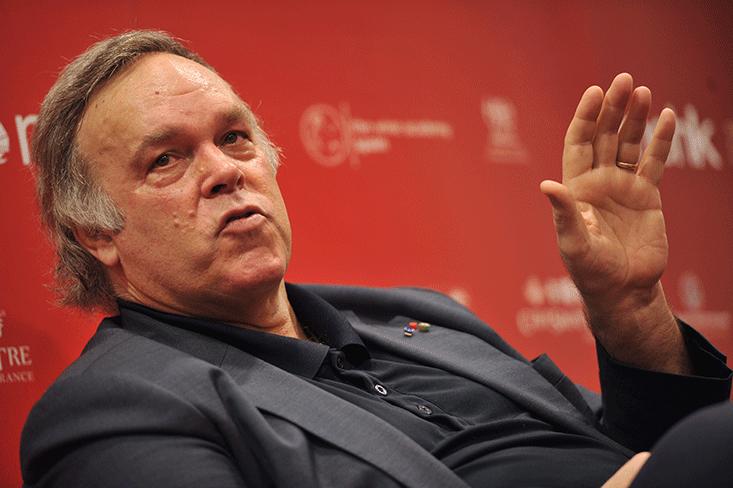

Then came the Americans, led by Robert Parker. A lawyer by training, Parker started his career as the world’s most influential wine critic by publishing a wine newsletter, gaining fame when he was faster than most of his rivals to identify 1982 as a classic vintage in Bordeaux. After this triumph, his Wine Advocate newsletter began to circulate widely in the trade.

Although price and expectation go hand in hand, price and quality do not.

Like his British counterparts, Parker carefully described the wines he rated, although he used a different vocabulary, based less on style than on a wine’s immediate impact on the taste buds. Suddenly, wines were jammy or leathery; they tasted of herbs, olives, cherries, and cigar boxes. But the most important ingredient of Parker’s formula was to rate wines on a scale of 50 to 100, exactly as his readers had themselves been rated for their performance in high school. No wine could score below 50, and between 50 and 60 a wine barely rated mention. A wine that scored between 70 and 79 was merely average; it had to score in the high 80s to merit serious attention. Here was a scale with which all Parker’s readers could identify, and although detractors railed (correctly) that such a finely graduated scale was ridiculous, there is no doubt that Parker has a highly discriminating palate and knows a good or interesting wine when he tastes it. Still, while the numeric scale gives wine ratings an aura of impartial objectivity, as human beings Parker and his colleagues remain creatures of preference. Rating something as diverse as wine in this way is a bit like asking someone to rate blues and yellows on the same preference scale: It can be done, but where each color tone will score entirely depends on which appeals more to the viewer. Still, there is enough agreement on what makes a wine great, or better than another, that a several-point spread will usually mean something significant to most people.

So the Parker rating scale caught on quickly, and was widely adopted. No longer did the wine buyer have to decrypt a critic’s lyrical description to decide whether he or she would actually like the wine described; now it was as simple as picking a wine that Parker had rated over 90. In turn, this meant a huge surge in demand for the wines that Parker liked, and prices for them rose accordingly.

Several years ago, as wines he had been accustomed to drinking regularly skyrocketed out of his financial reach, one of us rather sourly remarked to a wine merchant that he, at least, must have been happy with the Parker-driven price rises, which had presumably increased his margins. “Not at all,” he replied. “If Parker gives it over 90 I can’t buy it, and if he gives it less, I can’t sell it.” In its way, this is just as sad as the remark once made to us at a dinner party by an excessively affluent guest who declared that he only drank “the greatest” wines. Life, he said, was too short to drink anything else. It turned out that what he meant by “greatest” was actually “highest-scoring” and “most expensive.” Well, if ever a strategy were designed to cut people off from the captivating variety that is the most intellectually entertaining and sensually rewarding aspect of drinking wine, this must surely be it.

Parker has always preferred lush, powerful, in-your-face wines like those produced in the Rhône Valley or in the Merlot-dominated regions such as Pomerol and Saint-Émilion that lie to the east of Bordeaux. (“I enjoy full-flavored, but well-balanced, wines, but also many lighter styles as well. It is about balance, purity, and overall interest,” responds Parker.) So pervasive did his influence become that producers all over the world began to use the technologies available to them to produce alcoholic, fruit-forward wines that would score high on the Parker scale. Out the window went ideas of terroir, replaced by a search for the wine that would score a perfect 100 on the Parker scale. An analytic laboratory was even established in Sonoma that, for a fat fee, advises all comers on how to produce a Parker 90+ wine.

The world is not a static place, however, and the Internet has changed the rules of the game yet again, allowing a huge chorus of pundits a voice and simultaneously creating a more perfect market that has taken away much of the thrill of the chase. In what we can presumably take as a nod to the times, even Parker not long ago sold a stake in his newsletter to Singaporean interests. But there is no doubt that Parker’s precise attention to numbers and his detailed criticism caused fine winemakers worldwide to pay extra attention to both the growing of their grapes and their winery procedures, and it contributed to a general rise in standards that was also driven by improvements in technology.

The happy upshot of all of this is that today we have a greater range of high-quality wines and wine-drinking experiences available to us than ever before. But great as this news is, it does leave oenophiles with an unprecedented degree of responsibility. As Galileo so perceptively remarked 400 years ago, and as the neuroeconomists have now so meticulously documented, a wine’s sensory effects depend as much on the mind of the drinker as on the wine itself. Casually swigging cold white wine on a hot day can be fun and refreshing; but taking the trouble to know a bit about wine, and to learn just what you yourself prefer, will make the sensory experience of wine drinking a lot more rewarding.

Ian Tattersall is a paleoanthropologist and Curator Emeritus at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. He has written numerous books in addition to A Natural History of Wine, most recently The Rickety Cossack and Other Cautionary Tales from Human Evolution.

Rob DeSalle is a molecular geneticist and a curator in the Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics at the American Museum of Natural History. Along with A Natural History of Wine, his books include Welcome to the Microbiome, written with Susan Perkins.

Excerpted fromA Natural History of Wine by Ian Tattersall and Rob DeSalle, published by Yale University Press in November 2015. Reproduced with permission of Yale University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The lead photocollage was created from an image from EdStock / Getty Images