In 1777—after whipping local people for trivial offenses, spreading venereal disease, and clumsily avoiding a plot to kill him—the English explorer James Cook left the shores of Tonga laden with treasures. Not least among them was a word scrawled in his ship’s logbook: tabu, which he defined as “a thing that is forbidden,” like a fish that could only be eaten by kings or a lagoon where fishing was prohibited. Cook died not long after, but his crew brought the word back to Europe, where it gave rise to the English word taboo.

Yet while Cook may have been the first to write it down, tabu had traveled before. Thousands of years earlier, the ancestors of modern Pacific Islanders had carried the concept with them as they sailed dugout canoes to the specks of land that became their homes: the island groups of Polynesia, Melanesia and Micronesia, constellations in a universe of ocean. As a result, nearly every culture in Oceania has its own version of tabu. In the Marshall Islands, the practice is known as mo. Palauans call it bul. In New Zealand, it’s tapu.

“It's similar to what a western scientist might call a protected area, or a protected species,” says Angelo Villagomez, a senior officer at the Pew Charitable Trusts and a native Chamorro from the Mariana Islands. “You can pick an island and ask someone what their concept of a protected area is, and they’ll be able to give you the word in their own language.”

Taboos weren’t chosen at random. In pre-colonial Hawai’i, for instance, it was taboo for anyone but chiefs to eat a delectable silver fish called moi, or Pacific threadfin. This wasn’t just out of greed; Hawaiians knew that moi are born male and later become female, so if you overfish them before they reach their female breeding stage, the population won’t recover. This kind of sophisticated ecological understanding let Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders use taboos as social controls to protect species that were particularly vulnerable, or valuable to people’s survival. And because ancient islanders regularly voyaged across vast distances and shared similar cultural values, they often acted in concert to protect the same species. The effect was a network of marine protections that spanned the Pacific, safeguarding both local fish and migratory species like sharks.

But as the colonists, missionaries, and traders who followed in Cook’s footsteps violently suppressed Native people and knowledge, these protections frayed—and with them, the marine ecosystems that had supported Pacific cultures for millennia. In Hawai’i, after the U.S. government overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy and opened the waters to commercial fishing, moi and other fish populations plummeted. Similar scenarios unfolded across the world’s oceans. Today, over a third of marine mammals and members of the shark family are threatened with extinction, and just one-fifth of fish species caught commercially might be considered healthy. The ocean—the source of all life on Earth—is gasping for breath.

Yet even in the face of our growing global appetite, Western scientists have begun to realize what Pacific Islanders knew all along. To sustain the ocean's life, and our own, we must set aside sanctuaries where fishing is limited or banned. The International Union for Conservation of Nature says that to protect biodiversity, rebuild fisheries, and survive climate change, we need to set aside 30 percent of the ocean by 2030. Our best hope for conserving what’s left of marine life, in other words, is to build a global network of protected areas like those that Pacific Islanders created and managed for centuries.

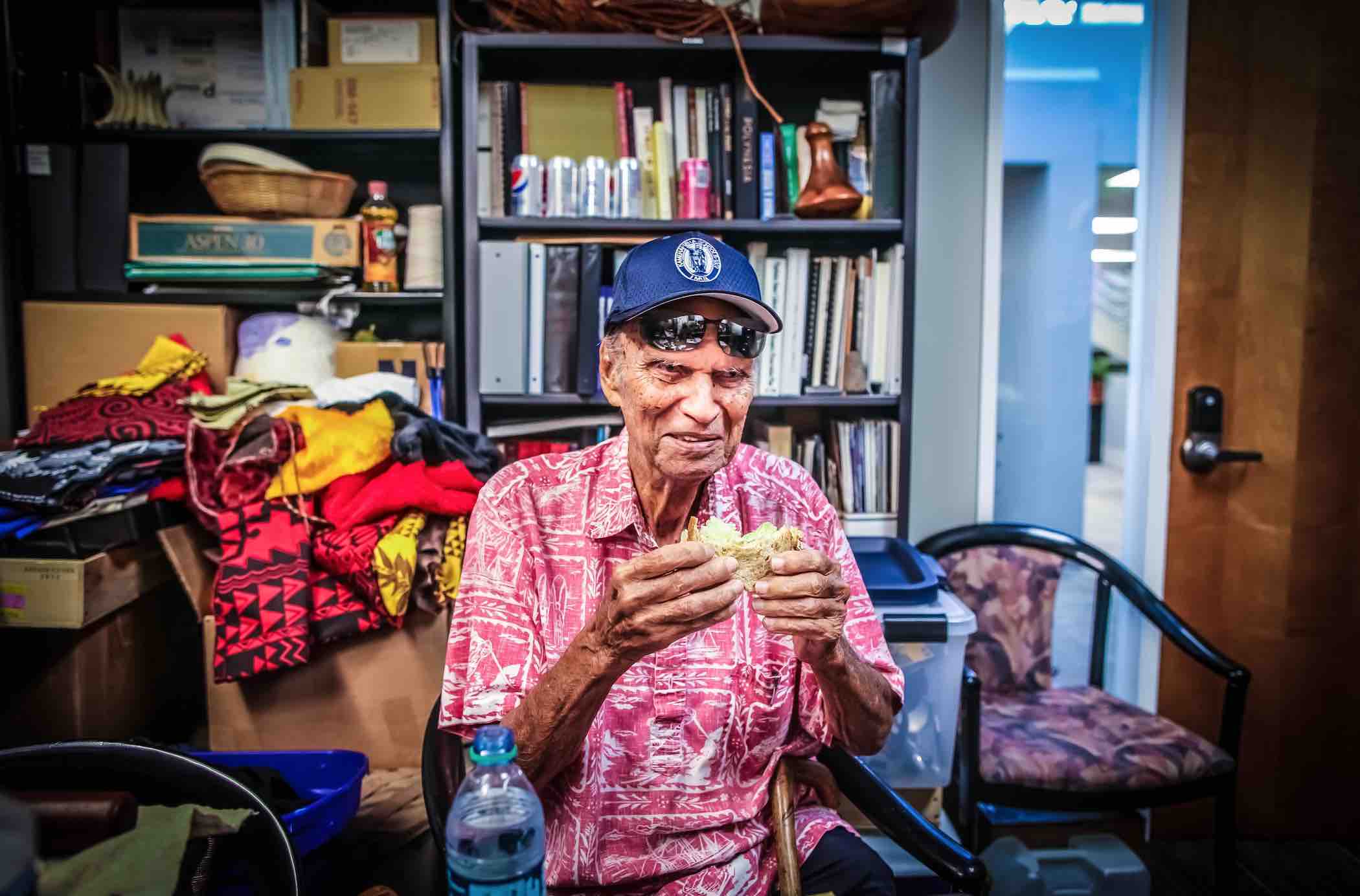

One of the first people to recognize that the expertise honed by ancient Hawaiians could be a tool for modern conservation was a fisherman named Louis Agard, better known as Uncle Buzzy. Born in 1924 to a Native Hawaiian mother and a Scandinavian father, Uncle Buzzy was an unlikely advocate for marine protection. He wasn’t from one of Hawai’i’s old fishing families, gifted with knowledge and techniques passed down for generations. He didn’t even have the money to buy fishing line or hooks. But he was drawn to the way that fishing connects us to a world other than our own; to an underwater realm of beauty and mystery. As a kid, he bent sewing pins into hooks and tied them to bits of twine, then earned pocket money by catching freshwater fish known as ‘oʻopu from the jungly banks of the Keālia River on Kauai. It was his first taste of fishing as a career and he was—sorry—hooked.

As a teenager, Uncle Buzzy moved to Honolulu, where he hung around the docks and learned to fish for skipjack tuna from Japanese fishermen. After World War II, he became a commercial fisherman himself—one of the few with the fearlessness and navigational skills to leave sight of the main Hawaiian Islands for the vast open waters to the northwest. There, among seas so turquoise they seem to glow, are a chain of uninhabited atolls and islands known as the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

In traditional Hawaiian belief, the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are the axis between the supernatural world and this one; the place where light and darkness meet. Chiefs voyaged to the luminescent waters to access mana, or power from their ancestors, and spirits journeying to the afterlife passed over the islands. But Uncle Buzzy didn’t know this significance. He didn’t know that Hawaiian custom required him to throw the first fish he caught back to sea for the fish god, or that traditional restrictions on where and how to fish existed to preserve the ocean’s bounty. He knew only the Western mentality, which was to take all he could.

Western scientists have begun to realize what Pacific Islanders knew all along.

So one day, when he was fishing in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and came across an enormous school of moi, the fish of kings, he hauled in his nets with abandon. “We caught them, of course,” Agard said in a 2010 speech at Native Books in Honolulu. “I thought, my God, this is nirvana.”

But Uncle Buzzy’s nirvana was short-lived: he never saw moi in the area again. He believed he caught their breeding stock and wiped them out locally. Over time, other fish species became less plentiful too, until one evening in 1956 when Uncle Buzzy had an epiphany. “When you sit out there hour after hour waiting to catch some fish, you begin to evaluate what you’re doing,” he recalled. He started his engine and headed for Honolulu.

"I never looked back,” he said, "and I never went back."

Back home, Uncle Buzzy began advocating to close the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands to fishing—sport fishing, commercial fishing, subsistence fishing, all of it. It was a radical idea from a commercial fisherman, but it wasn’t new. Agard had been researching how his ancestors had conserved Hawai’i’s natural resources for millennia, in part through reserves called puʻuhonua where fishing was banned. He learned how puʻuhonua, taboos, and other practices had supported fisheries that fed up to 1 million people—nearly as many as the 1.4 million who live in Hawai’i today. And he became convinced that the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands should be designated as a sort of modern puʻuhonua: a sanctuary not just for fish, but for Hawaiian culture and beliefs.

The United States government was also thinking about protecting the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. But instead of safeguarding their ecological and cultural values, politicians envisioned the area as a tourist destination.

It was the same rationale used to protect the world’s first national parks. In the late 19th century, when the American West was being plowed into farmland and sliced into roads, setting aside natural areas “for the benefit and enjoyment of the people” was a groundbreaking idea. And it made sense financially: enforcing environmental protections requires money, and money usually comes from tourists.

But “the people” who benefitted from the world’s first national park legislation and the myriad environmental laws it inspired were largely white. Indigenous people were rarely consulted on how protections would impact their well-being or the places they had stewarded since time immemorial, and Indigenous knowledge and practices were rarely integrated into park management. The sacred mountain of Mauna Loa, for instance, was ostensibly “protected” when Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park opened in 1916, even though Hawaiians had safeguarded the peak’s sensitive flora and fauna for generations through taboos that kept people at bay. The national park designation, conversely, opened the mountain to mass tourism. And the model carried over to marine conservation. As recently as 2010, the Chilean government created a no-take marine protected area (MPA) around an island called Motu Motiro Hiva without consulting the nearby Indigenous people of Rapa Nui, or Easter Island.

The U.S government’s plans to turn the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands into a kayaking and recreational fishing destination echoed this antiquated model, and felt to many Hawaiians like just another blow by a government that had already stripped them of land, resources, and autonomy. So Uncle Buzzy and other Hawaiians and allies built a local coalition, called a hui, and traveled to Washington, D.C. to advocate for protecting the islands in a way that honored Hawaiian culture and values. In 2006, after years of meetings and hearings, they prevailed. President George W. Bush designated more than 139,000 square miles around the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands as Papahānaumokuākea National Marine Monument—the United States’ first large-scale marine reserve, and the world’s first “cultural seascape.”

But though Papahānaumokuākea was a watershed moment for Native Hawaiians, decades of harmful environmental policies weren’t dismantled by a single pen stroke. “Everything was a fight,” recalls ‘Aulani Wilhelm, who served as the reserve’s first superintendent. The idea of giving Indigenous ways of knowing equal weight as scientific knowledge without it being “proved” by science was unheard of, Wilhelm says: “There were a lot of naysayers.” And on top of it, predominantly white, Western-educated scientists descended in droves, thrilled to have a “pristine” tropical sea as their research playground.

“There were, understandably, a ton of permit applications,” recalls Miwa Tamanaha, who worked on the effort to protect Papahānaumokuākea. “So there was also a need for increased vigilance. The idea was supposed to be that Papahānaumokuākea shouldn’t be just for anybody at any time. In Hawaiian epistemology, if you want to go someplace you ask permission, you have a purpose. You don’t just go to take.”

In October 2015, Louis “Uncle Buzzy” Agard passed away. A year later, President Barack Obama expanded Papahānaumokuākea by nearly 389,000 square miles, making it, at the time, the planet’s largest protected area of any kind—larger than all the national parks in the United States combined. The move set the stage for the creation of other large marine protected areas—defined as areas over 38,000 square miles—which provide refuge for species like giant manta rays who haven’t been adequately protected by smaller marine reserves, and which are integral to achieving the IUCN’s goal of protecting 30 percent of the global ocean. Papahānaumokuākea also inspired a new wave of marine conservation that weaves Indigenous voices into its very fabric.

The island nations of Oceania are at the fore of both movements. Today, nearly every country in the region has either recently designated a no-take marine reserve or is in the process of implementing one, says Angelo Villagomez. And many, if not all, are integrating traditional practices and values into their management. Even in Rapa Nui, where the Chilean government just ten years ago ignored the input of Indigenous people, a new 286,000-square-mile MPA was designated in 2017 after winning a local referendum with 73 percent support. Designed by Rapa Nui people, it bans commercial fishing while allowing Rapa Nui to continue subsistence fishing. The model is also spreading beyond Oceania to places like British Columbia, where 17 First Nations are leading an effort with provincial and federal agencies to create a network of coastal MPAs.

“That’s Gramps’ legacy,” says Kuni Agard, Uncle Buzzy’s grandson. “He will forever be known as one of the most famous fishermen in Hawai’i history, and someone who used his platform to remind people that if we don’t change how we take care of the ocean today, the fishing industry won’t exist. Unborn generations won’t have the same opportunities we had.”

These new MPAs benefit both people and wildlife. One study in Fiji showed that marine conservation goals were more likely to be achieved when local communities helped draft them, while another showed that biodiversity on Indigenous-managed terrestrial reserves in Australia, Brazil, and Canada is measurably higher than on federal or state-managed parks. Indigenous-led MPAs can also restore native peoples’ authority over their waters and resources, and help people reclaim practices nearly lost to colonization.

When President Obama expanded Papahānaumokuākea, for example, an agency dedicated to the well-being of Native Hawaiians called the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) became a co-trustee of the reserve, along with the state of Hawai’i, the Department of Interior, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The inclusion means that Native Hawaiians—including at least one elder—have equal input in management decisions. Native Hawaiians also get to review every permit application for every activity allowed in the reserve, from collecting biological samples to controversial practices like culling sharks who prey on endangered monk seals.

“It’s not so much about having veto power,” says ‘Aulani Wilhelm. “It’s the learning and the conversations that happen as a result of the review process, which influence how people think about ‘conservation’ and the relationship between humans and nature. That’s where having a cultural voice and sense of place is so beneficial.”

Today, Native Hawaiians regularly travel to the island chain for educational trips, to clean up marine debris, or to sail double-hulled voyaging canoes using traditional wayfinding techniques—a practice once on the verge of disappearing, in part because navigation in the main Hawaiian islands can be impacted by light pollution and coastal development. But in Papahānaumokuākea, it’s still possible to navigate using just environmental cues.

“It's this training ground,” says Kaʻaleleo Wong, a sailor and navigator who leads the Papahānaumokuākea Program for OHA. “When there's artificial light to help guide you to an island, you don't hone your other skills, like understanding birds or seeing the ocean refracting off the islands. These are traditional things that I think are important to remember, because they help you have a more intimate understanding of the environment.”

Yet while Indigenous communities have made great strides in the last decade, ensuring their involvement isn’t a panacea. For one thing, it only works if governing agencies are willing to cooperate. In Panama, a grassroots effort to allow Ngöbe Indigenous people to practice traditional fishing and harvesting within Bastimentos Island National Marine Park failed because the federal government simply ignored their proposals. Protections are also effective only if enforced, and the larger and more remote a protected area is, the harder it is to keep illegal fishing boats out. The Pew Charitable Trusts estimates that although 7.5 percent of the ocean, or 10.6 million square miles, is under some form of protection, roughly one-third of that is protected in name only, with little in the way of actual conservation benefits.

Indigenous opinion is also not monolithic. While many people applaud Papahānaumokuākea as a model for Indigenous-led conservation, Isaac “Uncle Paka” Harp, who drafted an early management plan for the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, says that the reserve is far from perfect. Hawaiians may have more of a say than Indigenous people had in past conservation efforts, but it’s still a far cry from sovereignty over their ancestral lands and waters. He also thinks there should be more involvement from “regular, everyday Hawaiians off the street” like he and Uncle Buzzy—the very people who led the effort to protect Papahānaumokuākea. And he says the Hawaiians who do have influence still let in too many scientists whose work doesn’t actually improve the reserve.

“I think that place would be best served if you just left it alone,” he adds. “People ask if I've been there and I say no, I've never been there because I have no purpose to be there. I just like to know it’s there, like a big shining star on the horizon.”

“I just like to know it’s there, like a big shining star on the horizon.”

Pacific Islanders say that the ocean connects them. While others may gaze across the open ocean and see a vast blue nothingness, islanders are more likely to see the realm of voyagers, the connective tissue between far-flung relatives, the waters that birthed their ancestors. It’s the home of air-breathing turtles who sleep underwater, rays who soar through space, whales who sing, fish who light up the dark—animals who breathe life and a wonder into our world. It’s the medium through which ideas and knowledge have passed for thousands of years.

In the centuries following Captain James Cook’s voyages, we’ve too often exploited the ocean’s connectivity to transport enslaved people and stolen resources, bombs and soldiers, boats upon boats teeming with fish bound for global markets. Today, as we sort through that wreckage, there’s hope that the ocean can again be a conduit for the kinds of ideas and practices that deepen our connection to the natural world. Words and concepts born in the Pacific are spreading around the globe, carried to places as distant as the Canadian Arctic, the Mariana Trench, and Norway. The concept of taboo is again traveling. Alone, it won’t undo the damage that's been done. But it represents a small step toward healing, and that’s at least something.

Lead image: Reef fish including ornate butterflyfish, pennant butterflyfish, and bluestripe snapper swirl around corals at French Frigate Shoals in Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. Credit: Mark Sullivan/NOAA Fisheries Hawaiian Monk Seal Research Program