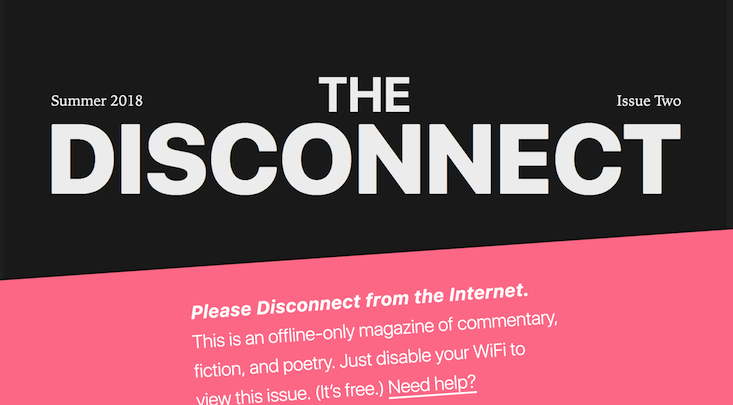

The latest cover of The Disconnect, a new online magazine, features an animated digital fingerprint that is unique to you, the reader. It tells you what browser you’re using, what time zone your clock is set to, and what kind of hardware your computer or device has.

Unlike most magazines and websites, though, this information is not tracked or stored. In fact, the magazine’s founder and editor, Chris Bolin, can’t tell which stories you’re reading or how long you’ve been on the site. That’s because, if you’re reading his magazine, you’re not on the internet.

When you browse to The Disconnect’s homepage, you’re greeted with an unusual request. “Please Disconnect from the Internet. This is an offline-only magazine of commentary, fiction and poetry.” Bolin, who is a software engineer, uses a browser feature to check whether you’re online, and will only show you an issue when you’re not. No cheating—connecting back online when you’re in the middle of a story will hide it.

The magazine presents the reader with a set of paradoxes: It can only be reached online, but can’t be read online. It shows you it can track you, but then doesn’t. Many of its stories are about internet behavior patterns that it is asking you to take a break from.

All of which holds a mirror to the suspension of disbelief that we all practice when we browse: belief that our privacy is not being violated, that free websites are really free, or that we can devote our entire attention to one online story. The Disconnect asks us to consider our internet lives from the other side of the looking glass. It is a quiet place, and a new kind of internet neighborhood.

I caught up with Bolin last week to chat about his creation.

What is the ideal Disconnect experience?

I would like to bring the same intentionality that people have when they sit down with a print magazine, to a digital form. And I want them to realize that their phone or their laptop can be really useful as opposed to really distracting. I think attention is a really beautiful thing. I think that getting lost in a novel is a very beautiful thing, and I would like people to have that experience with The Disconnect.

The magazine feels almost like a part of town you disappear into.

I was at a bar in Berlin, and they had a sign when you came in that said like, “No phones, no pictures, no computers.” But then they actually meant it. A very large man suggested that I not take my phone out of my pocket. And I liked that. My wife and I did go dark, had a great conversation, and met some people. I thought it was really fun. That’s basically what the magazine is—it requires a certain investment of disconnection.

Am I cheating by reading The Disconnect on my disconnected phone while browsing my connected laptop?

I’ve definitely read a paper magazine with my phone out to look things up. So that doesn’t seem unnatural to me. Are you cheating? I think that’s a really interesting phrasing, and it’s pretty common, too. I want to try to stay away from an ideological definition of disconnection. I want to think about practical disconnection instead, which is just saying, “What kind of being am I? How do I work best? How can I best use my tools?” Maybe disconnecting for 10 hours to get something done, or something read, is the best way of going about that. It’s very in vogue right now to talk about internet addiction and the danger of our devices, and I don’t quite buy into that; it seems too easy a narrative.

You’re encouraging your readers to think practically.

I hope people find a new practical tool in their toolbox: airplane mode on their phone, the WiFi icon on their laptop. Honestly, it sounds so simple but if people took that simple, practical message away, I would be very happy. One of the things I love is just sitting down uninterrupted and creating a thing. Disconnection really helps me do that. If I can help people disconnect for a couple hours, and dive into a problem, and hit that flow—that exciting experience of having an idea and actualizing it in the same mental stream—I would be overjoyed. And that is very, very practical—banal almost. That is not about high-level ideas. That’s simply a technique.

Do you believe some of the internet is a mind hack, exploiting our evolutionary programming in ways that we can’t control or resist?

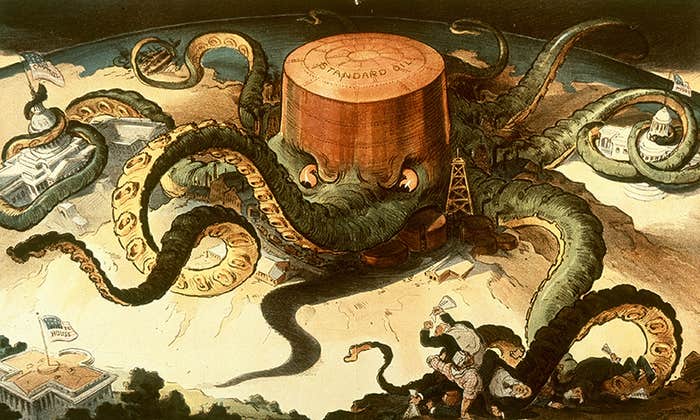

I actually believe more of that than I thought I would when I started looking into it. I have personally written recommendation systems and algorithms that take pretty benign information about people and their behaviors on websites to serve them ads. When you realize the power you have as a software engineer, it gives you pause. It is a little bit worrisome that you have an army of people with computational power aimed at you as an individual, trying to change your behavior. And that’s one of the reasons I’m personally drawn to the concept behind The Disconnect. You can gain some of the benefits of the modern world of the internet, but you’re removing some of the others. There’s no ads to click out on. There’s no fake news articles. There’s no native advertising.

The online experience can feel like you’re always hunting for something but never finding it.

Absolutely. Most of us are wandering around the internet hunting. And we’re not convinced that we’ve ever found the right kill. You keep scrolling. That makes me very leery, and I do it all the time. Like online advertising, it hits almost an unnatural resonance with us. It’s kind of like ice cream. Ice cream is not found in the natural world, and when you have it you just have to have more of it because it meets your needs almost too much. Infinite content, especially when it’s readily accessible, is almost too sweet for us. The Disconnect is my effort to see the hope in all of these tools that we’ve built, because I do find it very easy to see the downsides.

How did we let the internet become what it is today?

I try to think about things in pure economic terms, and I think things kind of ran away from us. If you had to pay for Facebook, it’d probably be something like $20-$150 a month. I don’t think people would pay that amount of money for that service, but they are worth that amount of money to Facebook in advertising. We’ve gotten used to free things, and we didn’t realize what we were giving away. The old, simple mantra is still true: there’s no free lunch. We just don’t realize how we’re paying for things. And we can’t go back because the whole business model is predicated on that.

Is the concern over the internet really so different from the concern we used to have over TV, and over radio before that?

I know that the rise of the personal radio ushered in rock-and-roll. And a lot of the older generation was very annoyed by that and thought that was the fall of civilization. I would love to find reports about people being annoyed about books. That would be really entertaining. Just think about this conversation: “Oh, yes. Our daughter just won’t leave her room. She’s always reading. She’s not talking with other people. She’s not interacting. She’s not telling stories. She’s not singing…” There is always a conversation about what we should or should not be doing. That’s why I’m a little leery of moralizing.

How does the content that you’ve published match the conceit of the magazine?

Who are the people who would be willing to do something weird like go to a webpage on the internet that requires you to disconnect from the rest of the internet? They are probably interested in technology, or are technology-adjacent. Also, what are the types of content that this kind of hybrid medium lends itself to? I think that longer fiction hasn’t really found a good place on the web because of the business models. If The Disconnect experiment is successful, it should lend itself to longer-form fiction. The reason poetry is there is probably my personal bias showing: I think poetry is a very beautiful art form. It doesn’t seem to have a large place on the internet, and I thought it would be fun, again in the spirit of experimentation, to try to give it a place.

Are you implementing some kind of offline behavior tracking of your readers?

No, we’re not. It would require a lot of work, and it’s slightly antithetical to our mission. But the greatest reason, honestly, for not tracking is that I don’t want that to define our success. I don’t want to invent a Key Performance Indicator. There would probably have never been an issue two if I just looked purely at the numbers.

Does Google crawl your articles?

If Google crawls The Disconnect, what they would see is what you see online. That is, the title, the art, the author’s name, and then the first 500 words of the piece. And then it cuts off kind of like a paywall would. So it is in some ways being crawled by Google, but not all of it. As far as I know, the rest of it is dark, and only exists for those people who disconnect.

How do you think about ads?

I’m drawn to how Offscreen magazine does ads. It’s a wonderful little print publication about the people who make the internet. One of the things that they do very well, and is very interesting, is advertising. They put all of the ads in the middle of the magazine in a standardized way. The ads are usually all on a black background with white text. The logos have to be monochrome, and there are only a couple paragraphs for the companies to write copy in. It’s almost like a gallery. It’s very different than the wild west of, “We give you this 200 by 700-pixel space, and you can put whatever you want into that.” In that vein, when Mozilla sponsored our second issue, they wrote a small article about why they sponsored us and who they are as a company.

It sounds like you have a great concern for boundaries.

Boundaries can be blurred for the better. When someone blurred the boundary between a desktop computer and a physical notebook, they came up with a laptop. I think that’s how a lot of innovation happens. But boundaries can also be blurred in a misleading way. I don’t want to mislead people, and I do very much want to value presentation, and attention, and intentionality. I’ve always been the kind of person who’s drawn to how a dish is laid out, not just how it tastes. And part of the value of the dish, or of a magazine, or a physical space, is the presentation of it, not just the practical value of it.

What have you learned so far from building and running The Disconnect?

One thing I’ve learned is that many, many people are thinking about the same thing that we’re talking about. Distraction and attention are very much on people’s minds. I’ve also learned that it doesn’t matter what your idea is, someone will hate it. And that there are very few technology problems, but there are a lot of collaboration problems. Getting people to collaborate on a magazine is much more difficult than I thought it would be. It has given me an appreciation that I didn’t have for management and leadership, and for marketing, for telling a cohesive story about an idea. I’ve also learned a lot simply from the writers themselves and what they’ve chosen to write about.

What are your own disconnection habits?

I use Slack at work. It’s probably the greatest distraction in my life, but it also enables me to do my job. So my first level of trying to disconnect and concentrate is just to close Slack. If I don’t believe that that is allowing me enough concentration, especially to write or to code, then I will simply disable my WiFi. There is also a kind of more extreme disconnection on the weekends. I’m new to the state of Colorado, and one of the reasons I moved here is because I wanted to be outdoors more and hike more. Last weekend I took a couple-hour drive into the mountains, camped for two days, had no cell signal, and that was very, very nice. I was able to think about ideas that I didn’t even know I wanted to chew on. That is something I strive for in my life.

Michael Segal is Nautilus’ editor in chief.