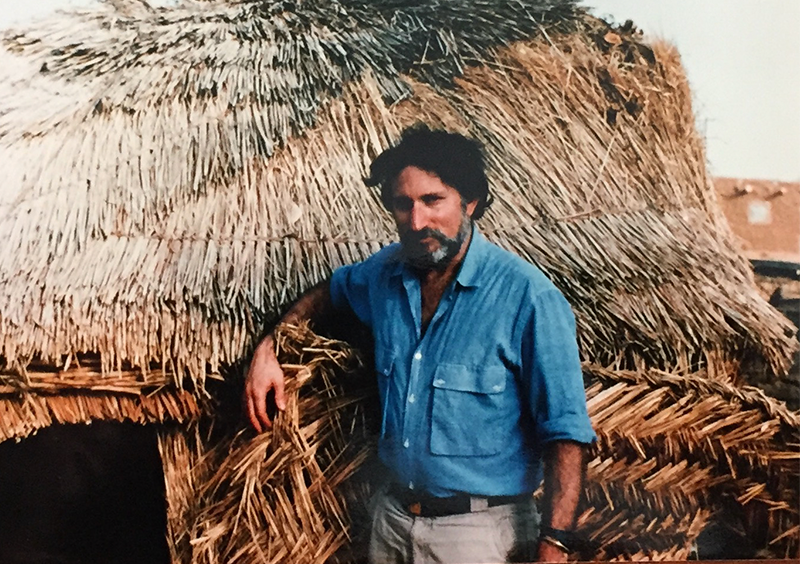

Once upon a time, in a thatched spirit hut in the Nigerien village of Tillaberi, the Songhay master sorcerer Adamu Jenitongo told the American anthropologist Paul Stoller that the bush was angry. “People who speak with two mouths and feel with two hearts anger the spirits of the bush,” Adamu Jenitongo said. “When the bush is angry there is not enough rain. When the bush is angry there is too much rain. When the bush is angry locusts eat our crops. When the bush is angry sickness kills our people.”

Today, Stoller is a professor of anthropology at West Chester University, a permanent fellow at the Center for Advanced Studies in the Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, and the author of 15 books. His awards include fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Anders Retzius Gold Medal in Anthropology, given once every three years by the King of Sweden. He is also what the Songhay call a Sohanci benya, a healer who did not inherit his powers but was taught—often a captive or an enslaved person, or, in Stoller’s case, a cultural anthropologist from the United States studying the medicinal properties of plants used in Songhay ethnomedicine. Stoller ended up apprenticing with Adamu Jenitongo for 17 years. He explained his teacher’s comment to me this way: “His whole thing was that when things are out of kilter, when things are out of balance, when there’s a lack of harmony in social relations, then we suffer as human beings.”

Who would deny the lack of harmony in social relations today? It felt like high time to ask Stoller, whose 16th book, Wisdom from the Edge of the Village: Writing Ethnography in Troubled Times, comes out next spring, about what he has learned during his long career, the phenomenon of “spirit possession,” and what wisdom we can take from the villages and people he has studied.

You’ve spent years in Niger and other parts of West Africa, and later in the West African communities in New York. What was the focus of your work in those places?

My early work in Niger focused on how local political actors used competing discourses of Islam and pre-Islamic spirit possession in the arena of village politics. I discovered that in Western Niger many local political actors—avowedly pious Muslims—tapped into pre-Islamic ancestral practices like spirit possession in their play for influence and power. In later work in Niger, I studied the healing properties of medicinal plants, many of which proved to be effective in the treatment of skin disorders, minor infections, gastrointestinal issues, and hepatitis. My teachers provided the names and treatment regimens of these plants and I later linked them to their scientific classifications. The research1 underscored the deep pharmacological knowledge that Songhay healers possessed, knowledge passed down from generation to generation.

In New York City, I focused on economic practices of Nigerien street traders who from the early 1980s to the present have sold a variety of items (African art, perfumes, pomades, baskets, and beaded jewelry). With few resources, they were able to use traditional economic practices, shaped through Islamic principles of trading, to build successful multi-ethnic and multinational networks that provided the wherewithal to build thriving businesses. In short, their past economic and cultural experience created for them an impressive degree of social resilience—a model of social adaptation in troubled times.

I’ve been observing and thinking about spirit possession for more than 30 years.

What kind of insights have you learned that can help us, or teach us something about what we can do better at this time of global calamity?

Our sorry state of being stems from the notion that we, as masters of the universe, can extract what we want from nature, which, in turn, leads to the “rich” mastering the “poor.” We need fundamental transformation. Adamu Jenitongo said that we need to listen to one another. We need to engage in deep listening. We need to be more modest about our capabilities, and we have to be much more respectful of the environment. If we don’t make these changes, our future will be exponentially worse. Listening is not just hearing what other people say. It’s tuning in to the other person. Such listening is a multi-sensorial experience. It does take a little bit of practice. In the end, these simple interpersonal practices can immeasurably enrich your life-in-the-world. In my experience, the results are transformative.

What was Adamu Jenitongo’s solution to the disbalance in the bush?

His immediate solution was to restore the balance. He would make offerings. He’d perform rituals. That was his solution.

Did it work?

To some extent, but, you know, people continue to do things that anger the bush, anger nature. What can one do in these troubled times? As an anthropologist it is my obligation to write, engage in interviews, and try to bring Adamu Jenitongo’s humane wisdom to the attention of as many people as possible. For example, a central Songhay offering is called the genji how. You start by speaking to the seven heavens and to the seven hells, speaking to the north, to the south, the east, and the west. When you recite this incantation, it focuses your awareness. It attunes your awareness to the environment.

And as an ethnographer/anthropologist, what have you learned yourself?

I have learned that it takes a long time to understand—even partially—the mysteries of social relations and the whys and wherefores of systems of cultural belief. Having sat and listened to my mentor, Adamu Jenitongo, for 17 years, I’ve learned to be more modest in my pursuit of knowledge, which means that one never stops refining one’s knowledge of the human condition. Everyone commits errors of interpretation. By confronting those errors, one gradually refines his or her comprehension of the world. I’ve been observing and thinking about spirit possession for more than 30 years but am still discovering new dimensions of a powerfully compelling ritual.

Describe “spirit possession” for us.

Spirit possession occurs when an external force colonizes the body of a person. In some cases, the possession results in a permanent change in the person’s behavior and/or identity, as when a person defies social and cultural norms—talking with invisible presences or behaving inappropriately, or sleeping in the cemetery or using foul language in public. The more common form of spirit possession is spirit mediumship, as when a spirit takes the body of a medium during a spirit possession ceremony, which features spirit music, the old words of spirit praise-poetry, symbolic costumes, and spirit objects. Once possessed, the medium speaks to the community on matters of social life, respect for the ancestors, sickness and health and life and death. In short, spirit mediumship underscores the existential issues that give shape to the human condition.

The experience of wonder leads us to change. It expands our imagination.

How does anthropology, as a science, reconcile with events like spirit possession?

As scientists, anthropologists have tried to explain spirit possession as a cult of affliction, the result of calcium deficiencies, an expression of cultural resistance, as an example of psychodynamic process or as a performance of cultural theater. These various approaches—sociological, biological, psychological, and performative—provide partial explanations, but fall short of explaining the total phenomenon. There is an aspect of spirit possession—it’s wonder—that escapes explanation.

Why does spirit possession escape explanation? What can’t you explain about it?

Spirit possession is greater than the sum of its parts. I attempted to extend explanatory theories to what I have witnessed over the years, and they tend to be insufficient. Asking an anthropologist to “explain” spirit possession is like asking Mozart to “explain” his music.

Do you believe this spirit is supernatural?

I don’t know if spirit possession is supernatural, but I do know that it is an intrinsic part of the social lives of many peoples for whom the natural and supernatural are part of an experiential continuum. Most anthropologists have witnessed events that defy explanation. How can a medium, who I know is monolingual in Songhay, speak French and other African languages? One can try to find explanations for these kinds of phenomena, of which there are many—or one can, as I have tried to do in my writing, describe a hot topic with a cool hand and invite readers to debate the ontological contours of the inexplicable.

If Western societies don’t have a vocabulary to explain such things, as you’ve said, is there a vocabulary to explain them?

There’s a wonderful quote by Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy. He writes about how there’s a certain set of experiences that defy explanation, where logic bites its own tail. And when you reach that point beyond explanation, then, he says, the remedy is art. The best way to try to describe events that defy explanation—and many of the events that I’ve witnessed defy explanation—is through narrative. And that’s the way, of course, that many Indigenous groups convey their wisdom from generation to generation.

One of my favorite anthropology books is the late Keith H. Basso’s, Wisdom Sits in Places. It’s a beautiful text that describes how Western Apache people consider space and place. For them, every place has a story attached to it, and that story gives that place its philosophical significance. Embedded in the story is the wisdom that that place embodies. The story is a kind of a covenant you make with the place. That place, the memory of which is preserved in stories, represents a whole set of historical events and experiences that are meaningful to that particular culture. The same is true for Songhay people: There are certain spots in the Niger River basin that are sacred spaces. But labeling them sacred spaces is reductive; it robs them of their full significance. I make this point in much of my writing, and certainly in my new book. In many respects we have lost our ability to take the time to tell stories. In our times, we tend to reduce complexity to a series of formulae. We think we can understand something that’s partially true. But there’s an awful lot of non-Western phenomena that cannot be reduced to a formula. These are phenomena that do not lend themselves to theoretical extraction.

I also think people have lost their capacity—and this is part of the ideology of explication—for experiencing the wonder of not being able to understand something, of not being able to explain things that are mysterious. For me, the experience of wonder leads us to change. It enables us to expand our imagination. It leads us to a space of creativity where we can devise things that can make life sweeter for us now and in the future. For me, the experience of the inexplicable wonders of Adam Jenitongo’s world fired my imagination, expanded my consciousness, and prompted me to try different forms (memoir and fiction) of anthropological expression. One thing is certain: The wonders embodied in the ethnographic record make anthropologists the custodians of important insights about the human condition, insights that could help us confront the life-threatening issues that define our troubled times.

Are you saying that what people in the West call science simply may not yet have “discovered” what people in the West called magic?

The great ethnographer Jean Rouch says: “There are things not yet known to us.” There is much in the world that defies explanation. Perhaps the way to approach these phenomena is to live through the experience and slowly come to a partial understanding, knowing full well it could take a lifetime to comprehend something as extraordinary as spirit possession. As Adamu Jenitongo liked to tell me, “To understand us fully, you’ll have to grow old with us.”

Anthropologists are the custodians of insights about the human condition.

In 2001 you were diagnosed with lymphoma, and you sought Western-style medical treatment: chemotherapy, immunotherapy. But you also have written a book, Stranger in the Village of the Sick, about how what we’d call magic helped you maybe bring yourself to remission, or survive that shock and grief of the diagnosis. How did you combine science and magic in your healing process?

I had learned from my teacher a great deal about healing the body which, for him, emerges from seeking harmony-in-the-world. When I began chemotherapy and faced my mortality, I didn’t know exactly what to do. My doctor described what was going to happen to me—the horrible side-effects of chemotherapy drugs. Then, I suddenly felt this inexplicable tingling in my stomach. At that time, I hadn’t really thought about my teacher, who had died in 1988. What’s more, it had been a long time since I’d been to Niger. In a flash I knew that my approach to cancer had to extend beyond the scientific. I realized that I needed to perform some rituals to bring harmony between my body and the external world.

And so, I told my doctor: That healing can’t take place if there is no harmony between the inside, my body, and the outside, the external world. At that moment, I recited the incantation I mentioned earlier, the genji how. I then spat in the direction of his office’s four corners—north, south, east and west. During each of my treatment sessions, which last up to four hours, I recited incantations not just for me, but for all the others undergoing chemotherapy or immunotherapy. In so doing, I felt that my teacher, although he was long dead, had my back. That knowledge gave me the considerable will to move forward, despite the uncertainty of my circumstances. In addition to the chemotherapy drugs and good doctor, I felt like I had a lot going for me. This other dimension of treatment enabled me to confront my situation with strength and a measure of grace.

And what was your good doctor’s reaction to your use of your other dimension?

He thought it was cool. If he hadn’t agreed, I would have changed doctors. He was interested in what he called complementary medicine, and he was okay with me spitting in his examination room.

So, here you are, a white man born in Washington, DC, performing rituals that you learned in the bush. How do you justify it, ethically? How do you approach the conversation around the extractive nature of anthropology?

It is a complex issue. I was not a seeker of a sorcerer’s knowledge, nor was I a seeker of an apprenticeship. A series of events pointed my teachers out to me, and they thought it was important for me to learn about their practices and their very particular way of being-in-the-world. My teacher saw something in me. He thought he could trust me to convey his knowledge to the next generation. He also gave me objects and materials for personal use as well as to help other people. I use what he taught me on a limited basis. Ultimately, I see myself as a storyteller who is committed to a faithful representation of this kind of knowledge. If I’ve done my job well, then people, including, of course, Songhay people, will appreciate what I do. The ultimate test of the material I have presented in my work is whether it is correct or not correct, whether or not it preserves the knowledge.

When Adamu Jenitongo died, his eldest son told me: “You know, Baba shared his knowledge with you. The reason he did was because we weren’t ready to learn it. He wanted you to pass it on. You must come,” he told me at Adamu Jenitongo’s mortuary ceremony, “and spend some time with us to teach us what he wasn’t able to.” They had much to learn about the healing properties of plants, about the power of incantations, and about the profoundly important relation of the village to the bush.

And did you?

Yes, that was my obligation. In all kinds of healing practices, at least in West Africa, the idea is that knowledge is precious, and you learn it over a long period of time. In time, you become the custodian of that knowledge. Your greatest obligation, however, is to pass that knowledge onto the next generation. If the knowledge is correct, it will continue to be used. Everything that I’ve written about my teacher and my own experiences as his apprentice, has been an attempt to convey the wonder of the world he exposed me to. My hope is that my work will in some way ensure that this knowledge will not disappear. My hope is that Adamu Jenitongo’s wise practices will persevere and that they will be recognized, appreciated, and extended to the issues that we face today in the world. ![]()

Anna Badkhen’s seventh book, Bright Unbearable Reality, comes out in October 2022. She is a Guggenheim Fellow and a contributing editor at Nautilus.

Lead image: GoodStudio / Shutterstock

Footnote

1. The results of Stoller’s research on plants were published in In Sorcery’s Shadow (Stoller and Olkes, University of Chicago Press, 1987); Yaya’s Story (Stoller, University of Chicago Press, 2014); and The Power of the Between (Stoller, University of Chicago Press, 2008). For further exploration Stoller’s work in Niger and New York City see Fusion of the Worlds: An Ethnography of Possession in Niger (University of Chicago Press, 1989); Money Has No Smell: The Africanization of New York City, (University of Chicago Press, 2002); and Wisdom from the Edge of the Village: Writing Ethnography in Troubled Times, forthcoming from Cornell University Press in Spring 2023.